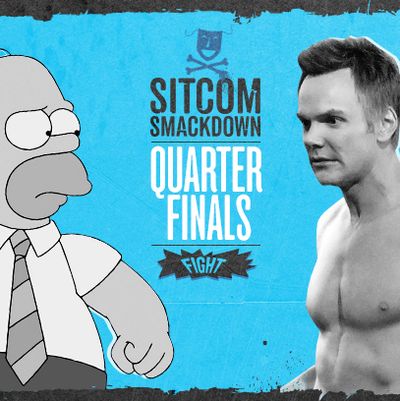

Vulture is holding the ultimate Sitcom Smackdown to determine the greatest TV comedy of the past 30 years. Each day, a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 18. Today is the third match of the quarterfinals, with author Steve Almond pitting Community against The Simpsons. Make sure to head over to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, which has already veered from our critics’ choices. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #sitcomsmackdown hashtag.

Back in the fall of 1989, my editor at the El Paso Times assigned me to write a story about a young cartoonist named Matt Groening. I was a fan of his work already, by which I mean the comic strip “Life in Hell.” Groening was in town to talk up his new animated television show The Simpsons, which was about to debut on Fox. (That El Paso showed up on his promotional itinerary at all may be taken as an indication of the network’s meager expectations and/or abject desperation.)

We went to lunch at a Mexican place. Groening, who, unlike me, did not wear his hair in a business-casual ponytail, endeavored to explain the concept of the show. He may have used the word subversive. I wasn’t listening that carefully. The project sounded doomed: Who would want to watch the travails of a cartoon family? I remember even feeling a little sorry for Groening. Here was this brilliant indie cartoonist selling out to the lamest of networks.

I know how to pick ’em, don’t I?

Twenty-four years and 523 episodes later, The Simpsons is widely recognized as one of the most influential shows in television history, an animated sitcom that has done more to investigate, excoriate, and influence our national culture than any dozen live-action series combined.

The Simpsons can be counted on to strafe the familiar targets: consumerism, corporate greed, religious hypocrisy, depraved clowns. But its essential mission is to expose the false pieties of its viewers, the manner in which most Americans actually stumble through life — as entitled hypocrites addicted to our own gratifications, full of good intentions (or at least self-flattering ones) and bad impulses.

Set against the prevailing treacle of Full House, Growing Pains, and Family Matters, The Simpsons also presented a radically candid vision of family life: sons who were selfish, cruel, and unrepentant; fathers who were lazy, bitter, and drunk; mothers and daughters helpless to corral these anarchic impulses. In Bart and Homer Simpson, Groening and his writers forged the archetype that would come to dominate our sitcom landscape: the lovable sociopath. Without them, there is no Cartman or Costanza, no Larry David or Lucille Bluth, no It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.

What allowed us to love this dyad, and the equally misanthropic cast that grew up around them, was the vulnerability exposed beneath their scheming. This is what makes The Simpsons so exciting to watch ultimately — not the razor wit or cultural smarts, but the fact that every character, from Mr. Burns on down, has a complex and tortured internal life. Like us, they all harbor secret desires and fears.

I am thinking here of an episode such as “Brother From the Same Planet,” in which Bart, feeling neglected by Homer, gets a Big Brother. Homer retaliates by signing up to be a Big Brother to an orphan. What’s astonishing is the manner in which father and son confront one another: They speak in the clipped, breathless tone of betrayed lovers.

Homer, desperately seeking reconciliation, seats himself on Bart’s bed. “Remember when I used to push you on the swings?”

“I was faking it,” Bart mutters.

Homer leaps up from the bed and shrieks, “Huh? Liar!”

“Oh yeah,” Bart says. “Remember this.” Then he starts shouting in ecstasy: “Higher dad! Higher! Wheeee!”

“Stop it!” Homer shrieks.

“Push higher, Dad! C’mon! Higher, Dad! Higher!”

Homer runs from the room, moaning in despair.

Intimations of homosexual incest in prime time? You betcha!

In the end, Homer proves his paternal devotion by brawling with the Big Brother, and bonds with Bart by rehashing its most gruesome moments. The “lesson,” as such, is that redemption resides not in the process of moral improvement, but a shared surrender to our infantile impulses. That’s dressing it up a bit, I guess. A simpler version: We are all freaks seeking love in a world bound to disappoint us.

Which brings us to Community. By its third season, the show had already become among the smartest and most innovative sitcoms ever to appear on network TV. Creator Dan Harmon started by jettisoning virtually every trope in the sitcom arsenal: crazy relatives, romantic tension, workplace frustrations. In casting off these conventions, the show has blossomed into a genuine sui generis phenomenon, a kind of absurdist collage of pop-culture homage, rapid-fire banter, metaphysical conjecture, and incessant genre-bending.

The basic setup — seven diverse strangers come together to form a study group at a failing community college — might sound like one of those cheesy surrogate family deals. But from the beginning, Harmon pushed his talented ensemble cast in the darkest possible directions. They’re constantly exposing, then trampling, one another’s self-delusions and ambitions. They’re not so much a study group as a wolf pack of fragile co-dependent narcissists.

What distinguished Harmon’s Community was his ability to place stunning visual and narrative experimentalism in the service of his oddball characters. Consider last season’s potent mindfuck “Digital Estate Planning.” In this episode, Pierce Hawthorne (Chevy Chase), the group’s designated bigoted white old guy, learns that he and the gang will have to defeat his biracial half-brother in an antiquated video game in order to claim his inheritance. The object of the game: to kill their race-baiting father. It’s Oedipus Rex meets Super Mario.

Most of the episode takes place within the actual video game. We watch a pack of avatars, voiced by the actors, stumble through an incredibly elaborate and devious pixilated universe. By the end of the game, Pierce’s Oedipal rage trumps his racism. “Get in there and kill our dad,” he exhorts his brother.

I’m sure I missed a hundred jokes intended for video-game geeks. But you don’t have to be a Nintendo savant, like Abed, to enjoy the show. Harmon and his writers relentlessly mined pop culture for their riffs. But the humor is always grounded in the tender psyches of his cast. They’re all damaged souls attempting to navigate their own failures in a universe that keeps going existentially haywire.

When I was initially asked to judge this bracket, I assumed it would be a romp — a tournament favorite up against a young and scrappy eleventh seed. As I revisited the shows, I couldn’t help but feel that I was more interested in watching Community. It felt fresher, funnier, and more adventurous.

Does this mean I’m calling for an epic upset?

Not exactly.

The truth is, much of what makes Community so exciting is its novelty. But Harmon was fired by NBC, and season four, with two new showrunners, has gotten off to an unpromising start. It may wind up as just another show that dies young and leaves a beautiful corpse. (Yeah, I’m talking to you, Arrested Development.)

To put things in perspective, I went back and watched a few episodes from The Simpsons’ golden age (seasons five to eight). It was immediately obvious that the show had been overtaken by the very revolution it spawned. The subversive wit and meta brinksmanship Groening and company championed two decades ago has become the culture’s default setting. What’s more, its writers face the staggering challenge of trying to come up with new ideas after 24 seasons. This explains the proliferation of celebrity cameos and topical plot twists.

In fact, Harmon himself — who often used his show to investigate the multiple contingencies of fate — would have to agree that, without The Simpsons, Community would never have been green-lighted in the first place.

Winner: The Simpsons in an OT thriller.

Steve Almond is the author, most recently, of the story collection God Bless America.