“One of the problems of things being long ago is that the heat goes out of them,” says Salman Rushdie, almost 25 years after Ayatollah Khomeini sentenced him to die, Rushdie is still probably the world’s most famous living writer. It’s the morning of the death of Margaret Thatcher—a political enemy of Rushdie the thirtysomething who became a guardian and defender in what he calls sweetly, several times, “the case of me.”

“She was very charismatic, and knew exactly who she was, and didn’t give a damn if you didn’t like it. I’ve never been a Conservative voter—no secret there. But when I needed it, she offered me what I needed to stay alive.” Imitating their first meeting, a few years into his hiding, he pats my arm reassuringly, turning me into him and himself into Maggie. “When you think of the Iron Lady, and then she comes on like your auntie—that was very unexpectedly tender.”

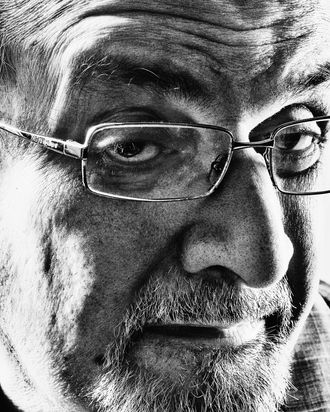

We are sitting in the rooftop terrarium of a Grand Central orbit hotel, slouching toward each other in low-backed chairs, he a little less sloppily than I. Like many executive-age men, he has come to grooming late but with vigor and no longer looks so much like recluse-era Stanley Kubrick when explaining how he came to not only write the screenplay for Deepa Mehta’s sprawling film adaptation of his 1981 novel Midnight’s Children, opening this week, but also perform its conspicuous voice-over narration. “I really wanted to be an actor,” says Rushdie. “It was the other thing I wanted to be. What’s difficult for me to work out is that, given that I was very involved in theater, and given that I was very obsessed with movies, I ended up doing this thing that you do by sitting alone in a room.”

There are not many literary novelists who could deliver a publicity boost to an epic movie spectacular, or whose voice might be helpfully recognizable to moviegoers not just here but in India, Canada, and England (where Midnight’s Children has already played, to mixed reviews). And it’s likely that, despite what Rushdie says about being reluctant to include narration (“The script that we shot had no voice-over at all”); and about Mehta having to insist that he perform it himself (“What Deepa wants, Deepa gets”); despite all that, it’s likely that Rushdie’s voice-of-God role in the film will be seen as a flourish of authorial vanity. Vanity being an unmistakable quality of Rushdie’s for which he has gotten an unforgivable amount of shit lately, especially around the publication of his fatwa memoir, Joseph Anton, last September.

The effect of the edict for writing The Satanic Verses was strange. Going into hiding made Rushdie enormously famous and then, especially after he began to reemerge, enormously disliked. As though the kind of celebrity that came to him in the wake of the fatwa was, like other kinds of celebrity, one the public expected to be paid back for—on its own terms, of course. Those terms seemed to be, basically, that Rushdie be a literary saint, more fully devoted to the cause, and less distracted by gossip, than the readers were. And those readers did seem to be really distracted by the gossip—about his getting involved with a series of famous women and then being bad to them, his taking a cameo in Bridget Jones’s Diary, his entertaining an invitation from Dancing With the Stars. Instead, he’s had the bad luck, or bad taste, or maybe good wisdom not to be—to come out of hiding not more committed to the novel but seemingly less. Which puts us readers in a tight spot: What are we supposed to do when the guy burdened with representing the cause of free expression turns out to be not all that gracious about it, possibly kind of a jerk, and, while undeniably gifted, maybe not the writer of his generation—or, in any event, not quite the writer he was before? One nasty answer has been to suggest that he was asking for it—at the time of the fatwa, Roald Dahl called Rushdie “a dangerous opportunist,” and was cheered for it. Another has been to pretend that the whole affair, which left over a dozen dead (including one of the translators of The Satanic Verses) and landed Rushdie in a one-man exile, circumscribed by radical Islam, was actually a trivial thing. In one hostile review of Anton, Zoë Heller charged Rushdie for failing to treat the experience with enough ironic distance.

“There were a couple of really spiteful pieces written, but nobody gets 100 percent,” Rushdie says, and then, laughing—“I got a good review from Michiko Kakutani. When does that happen? Some said, ‘He drops too many names, he knows too many famous people.’ But fuck it, so I do. What am I supposed to do? Deliberately make people anonymous just because they’re well-known? One of the pleasures of telling this story was to be able to say who did what for me. The fact that it was Margaret Drabble who moved out of her house so I could live in it. The fact that when I was invited to speak at MIT, Susan Sontag agreed to be my beard—she went there to do an event and then said, ‘Actually I’m just here to introduce him.’ How does it become wrong to mention that very eminent people did very brave things for me?”

Earlier efforts to adapt Midnight’s Children, which follows the children born at the moment of India’s independence through thirty years of struggle (including war over Bangladesh), ran aground because of the fatwa, he says.* “I had given up on the idea of a film. I thought, truthfully, I don’t care. The book’s still there.” But Mehta persuaded him, not just to sell her the rights (“a ferocious bargain”), but then to adapt the 600-page novel, first into a two-part screenplay they couldn’t interest a single investor in, then a filmable feature script. “You have to be just savagely ruthless,” he says about the process of writing the screenplay, his first. “You have to make space for film, you can’t just have the script filling up two hours.” For guidance, he put together a syllabus of the best book-to-movie adaptations (John Huston’s The Dead, Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence), then taught the class himself, at Emory, where he’s a writer in residence. “Everybody was saying it was a book that couldn’t be filmed,” he says. “We just thought, Fuck that!”

“This is a very important book for me, it’s a book that actually gave me the confidence that I could be the writer I had hoped I could be. Big moment in my life. I would have hated to just step away from it and go into the opening night, and think, Oh my God, that’s not what I want at all. I wanted to be implicated in it. If the film’s no good, I want it to be my fault, too—I don’t want to just blame someone else. So you roll up your sleeves and go to work.”

*This article originally appeared in the April 29, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been corrected to show that the war in India portrayed in Midnight’s Children was over Bangladesh, not with it.