Mad Men is a claustrophobic show. It’s set in Manhattan, which contributes to the boxed-in aesthetic, and mostly takes place in high-rises, an even more constricted environment. And it’s about hitting a very small target, trying to give people what they want and what you want at the same time. Episodes like this week’s “The Crash,” in which people are holed up at the office, tighten that grip a little harder. Throw in some drugs, and all of a sudden panic really starts to set in. “The Crash” is not the only Mad Men episode to follow that formula, though. Sure, this was a whackadoo episode that left a lot of people scratching their heads – or just plain irritated — but it’s also a mirror of one of the series’ highlights. “The Crash” is a weird reimagining of season three’s “My Old Kentucky Home.” And in reworking those themes, “Crash” winds up creating a totally different worldview for the series.

“Kentucky” is the third episode of the third season; Don and a very pregnant Betty begrudgingly attend Roger and Jane’s Kentucky Derby party, where Roger puts on blackface and serenades his young wife. Elsewhere, Joan’s shitheel husband Greg makes her play the accordion and sing “C’est Magnifique” for their guests, while Peggy, Paul, and Smitty get really high at the Sterling Cooper offices and try to come up with a campaign for Bacardi. “Kentucky” is straightforward where “Crash” is opaque, but so many small details pop up in both.

First, the dancing. In “Kentucky,” Pete and Trudy do a perky Charleston.

And in “Crash,” Ken’s dance is an instant classic.

In both of these instances, the dance is an awkward cover for some kind of wound. In season three, Pete and Trudy are still struggling to conceive, and Pete is devastated that he and Ken were promoted at the same time. (“Why can’t I get anything good all at once?” he whines.) He’s sad at home, he’s sad at work, and yet here he is with a plastered-on grin, shimmying so effectively he and his wife clear the dance floor. Ken’s injury is more literal: He hurt his foot on a lunatic joyride with the Chevy people, and yet thanks to the amphetamines, he feels good enough to tap dance. Oh, he’s miserable — “It’s my job!” he sings, sarcastically — but hey, as long as he has that cane, he might as well use it.

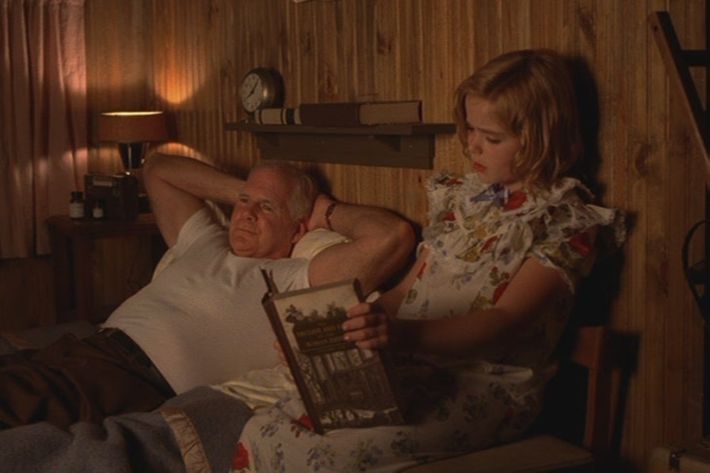

Second, Sally has a big story line in each. In “Kentucky,” Grandpa Gene is living with the Drapers, and Sally and he have a special bond. At night, she reads out loud to him from The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. But she’s a little kid with bad impulse control, and she steals five dollars from him — but given his worsening dementia, no one really believes him when he says it’s missing. Later, with her guilty conscience, she pretends to “find” it on the floor, and Grandpa Gene pretends to believe her.

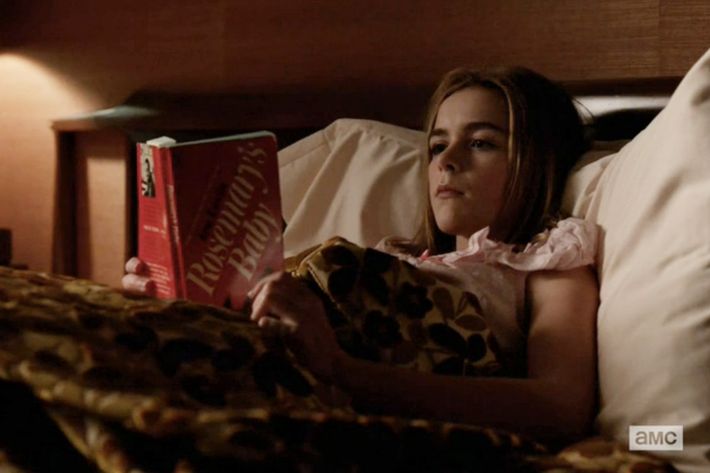

“Crash” gives us a spin on that, with Sally once again reading (this time Rosemary’s Baby; and if we’ve seen her read other books, I can’t think of them) and then interrupting “Grandma Ida” mid-robbery. Sally’s skills of deception have developed, enough so that she can play along with the intruder and then try to call 911.

Third, there’s the surprising touch of a stranger. “My Old Kentucky Home” introduces us to Henry Francis, who’s clearly and immediately taken with Betty. And she by him, really; they spend a lot of time at the party discretely gazing at one another. Eventually, he bumps into her near the bathrooms at the country club, and their very charged conversation leads him to ask if he can touch her pregnant belly. Betty has spent much of the episode complaining about how uncomfortable she is and how ugly she feels — which is catastrophic for her. Suddenly someone thinks she’s beautiful. Sexy, even. And she can’t quite believe it. In retrospect, she could have married him right then.

Don spends “The Crash” feeling pretty disgusting, too, not just from the speed but from his recent heartbreak. He’s stewing in this combination of guilt and rejection and confusion and longing and the self-loathing that comes from being a whore-child — and then some hippie-dippie girl wants to listen to his heart. His heart? His gross, mean, shriveled, unkind heart? Yes.

Fourth, the drugs. “The Crash” is mostly about drugs while “Kentucky” is also about other things, but altered states play a big role in both episodes. In season three, Peggy, Paul, and Smitty are struggling to come up with something catchy for a Bacardi campaign, so Paul calls his old college buddy who is now a drug dealer. Peggy’s secretary implores her not to get high, but she’s Peggy Olson. And she wants to smoke some marijuana.

And in weedo veritas. Peggy gets more creative, Paul gets more competitive and petty, Smitty gets more ignorable. This is who these people really are, and a similar letting down of the guard happens in “The Crash.” Stan is especially reckless and competitive. Don is especially self-destructive and neglectful. They’re themselves, only more so. And worse.

Apparently when you get fucked up at Sterling Cooper, or SCDP, or whatever the new incarnation will be called, you like to recite poetry. In “Kentucky,” it’s Paul laying on the floor reciting the end of “The Hollow Men”; in “Crash,” it’s Peggy quoting “the child is the father of the man” from “My Heart Leaps Up.” Maybe John is right, and everyone is pretentious.

“This is the way the world ends” is the line Paul quotes. And that’s what both “My old Kentucky Home” and “The Crash” are about. How do things end? In “Kentucky,” it’s about a cycle — things end because new things take their place. Things end because they change. Betty and Don might not know it yet, but that party is the absolute end of their marriage, thanks to Henry Francis’s appearance. Joan throws the dinner for Greg’s colleagues in the hopes he’ll move up a rank at work. That’s what The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is about: new ideas taking over for old ideas, even if those old ideas were better.

But the outlook in “The Crash” is much bleaker. There’s no cycle. It’s just a march to finality. “I know you’re all feeling the darkness here today, but there’s no reason to give in,” a strung-out Don tells his employees. It’s too late, though; the darkness already won. Don and Megan’s marriage — or at least the good part of it — is over, not because something new will take its place but because of the exact opposite. Don and Sylvia are not going to replace Don and Megan: Don and nobody are going to replace Don and Megan. Rosemary’s Baby is about the conception of living Satan, an accidental but suddenly unavoidable catastrophic fate. Everything is marching to one dark inevitability.

Such is the fall of Don. In season three, he thought he could escape the gravitational pull of his terrible childhood, that he really could get better or be different. By season six, it’s clear that isn’t true, and however far away his orbit maybe got, Don’s hurtling back now, about to, well, crash.