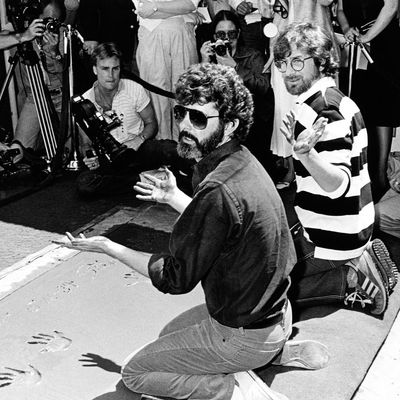

A few weeks ago, in a televised symposium, Steven Spielberg predicted the “implosion” of Hollywood as a consequence of blockbuster mania while George Lucas sat next to him, nodding. “You’re at the point right now,” said Spielberg, “where a studio would rather invest $250 million in one film for a real shot at the brass ring than make a whole bunch of really interesting, deeply personal—and even maybe historical—projects that may get lost in the shuffle.”

Most of us heard this and thought, Holy crap. These are not upstarts looking to shake things up. They’re the moguls credited with ushering in the age of the modern blockbuster with Jaws and Star Wars. More recently, Lucas was responsible for the grimly overinflated Star Wars prequel trilogy while Spielberg co-produced the toy-based “tentpole” Transformers and its sequels. If they’re sounding the horn …

Producer Lynda Obst makes many of the same points in Sleepless in Hollywood: Tales From the New Abnormal in the Movie Business. Underneath her lucid prose you can discern a howl of pain: The book is, in part, a lament for her inability to get her kind of movies into production anymore. Obst isn’t some indie maverick. She once described herself to me as a “company girl.” She’s happy working on a studio lot to develop mainstream films like Sleepless in Seattle, Contact, and How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, although she has also made darker movies with big stars (The Fisher King, The Siege), and she spent years trying to bring Philip Roth’s American Pastoral to the screen.

Obst recently worked with Spielberg on a project called Interstellar, which ultimately ended up with Christopher Nolan at the helm. (She’s co-producing with Nolan and Emma Thomas.) So I turned to her for some perspective on what the hell is going on.

David Edelstein: What do you make of what Spielberg said? And why is Hollywood in a death spiral, if that is what it is?

Lynda Obst: I think no one is smarter than Steven about the business. Not only did he make a blockbuster in his twenties, he has also run a studio, DreamWorks SKG, so he has seen it from both sides. What he said is true. But it wasn’t that the business is in a death spiral, exactly; 2012 was the highest-grossing year in ages, while 2011 was terrible. But if, say, four huge tentpoles were to go down at the same time in the same season, it would be catastrophic. It would be the ultimate challenge to the model that emerged in what I call the New Abnormal. The seeds of this model’s destruction are in place. There are fixed costs for these kinds of movies that are immense. And all formulas will only work for a while. How many times can you see the same cities destroyed? How many ways are there to destroy them?

D.E.: I don’t have knee-jerk dislike for $250 million pictures: I enjoyed Iron Man 3 and Fast & Furious 6 on their own dumb, machine-tooled terms. But it’s terrible if sequels, remakes, and “reboots” use up all of a studio’s resources—if they come at the expense of other kinds of movies. The obvious question is: Why is this happening now? Would you pin the blame on Hollywood’s increasing dependence on the foreign market—what I called, in my Man of Steel review, “truth, justice, and the Chinese way”?

L.O.: Yes, indeed. China is the No. 2 market now. In 2020, it will be No. 1. That’s why movies must all be sequel-ized or sequel-izable. So that they become more and more familiar to the international audience, where 80 percent of the profits are now coming from. We can’t afford to spend the same kind of money marketing movies internationally that we spend here, so we need pre-awareness: titles and characters that are already known. International audiences love action, wild and exciting special effects that can only be created by our technology. No nuance. Not so good for so-called writing. And China won’t look at anything that isn’t 3-D, which means everything is made that way—even with domestic audiences rejecting it.

D.E.: This raises so many questions. Not long ago, Hollywood made 80 percent of its profits domestically and 20 percent internationally. Now it’s the exact opposite. Why this violent shift?

L.O.: The percentages changed with globalization. It began with Russia and China building an enormous number of theaters as their countries opened up economically. And product like Titanic and Avatar was so enticing to them that it galvanized the rest of the world, even countries like South Korea and India that have their own indigenous movie industries. We were giving them stuff with the kind of bells and whistles that no one had ever seen before. The U.S. population is only 5 percent of the world—and suddenly we knew it. For the movie business, the foreign market came just in the nick of time, because in 2008, the DVD market that had been such a cushion collapsed.

D.E.: In the publishing industry, best sellers by people like Dan Brown generate profits that are cycled back into the company to pay for smaller books that will never have the same kind of upside. Why isn’t that the case in Hollywood?

L.O.: It was the case when we had that DVD cushion—big hits paid for smaller movies. But now that big hits cost so much, big hits pay for more would-be big hits. And everything else lies dormant.

D.E.: I guess that’s why you’ve moved into television.

L.O.: I started doing television, too, so I could keep making up original ideas and do drama. Writing and writers are critical to success in TV. Also, I needed to do something to pass the time between features, or I’d lose my mind.

D.E.: In your book, you talk a lot about how hard it is—harder than ever, and it was never easy—to make female-centric movies. Why are studios so nervous about the female audience?

L.O.: The big mystery. All I know is this: The movie marketers believe that women go to guys’ movies if they’re good, but guys won’t go to women’s movies ever. I’ve proved that wrong—as have many others—but they deeply believe that. And every time a women’s movie works, they attribute it to the star, not the audience, even if the star has never opened a movie before. Also: Chick flicks don’t tend to be sequel-izable. That’s the best I can do. It’s Chinatown, Jake.

D.E.: Would Chinatown even get made by a studio today?

L.O.: Don’t make me answer that.

*This article originally appeared in the July 8, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.