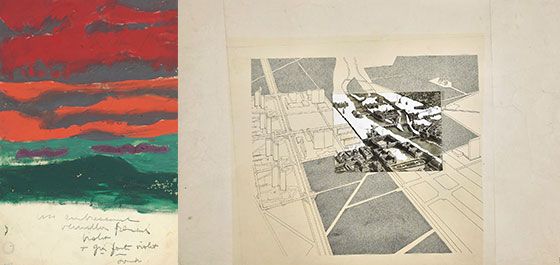

The most chilling image in MoMAÔÇÖs essential and long overdue Le Corbusier show is an aerial view of Paris from 1937, with all of the ┬¡inconveniently tangled bits ┬¡between the monuments neatly whited out. To leave room for the Louvre and Notre-Dame to breathe, the most influential urban planner of the twentieth century simply erased jagged streets, jumbled shops, and damp apartment buildings with their dark staircases and gloomy courts. To the modern mind of the thirties, much of urban life was insalubrious, and ┬¡Le Corbusier saw himself as a surgeon, ministering to diseased cities. But what he really craved was a chance to rip out their hearts.

When the self-invented genius, who was born Charles-├ëdouard Jeanneret, died, in 1965, he bequeathed an explosive package of ideas that invigorated architecture and nearly destroyed cities. Architects have never stopped paying tribute to him. ┬¡TodayÔÇÖs penthouse with wraparound glass, the sinuously contoured concrete wall, the floodproof building raised on stilts, the roof garden, the lonely high-rise encircled by open spaceÔÇöall began as Corbusian ┬¡formulations, grew into causes, and ┬¡eventually degenerated into clich├®s. He developed the horizontal ribbon window as an architectural panorama, for instance, allowing the eye to sweep along a lake or a mountain range, instead of confining it to a fixed, framed box. His principles were cheaply invoked, his signatures easily forged, which gave him an unearned reputation for designing abstract forms that could be plunked down on any bulldozed flat. But the MoMA retrospective makes clear that both he and his architecture ┬¡always reacted forcefully to his surroundings. Born in Switzerland, he lived in Paris and drowned in the Mediterranean, an arc that seemed to express his obsessions with hill, metropolis, and unbroken horizon.

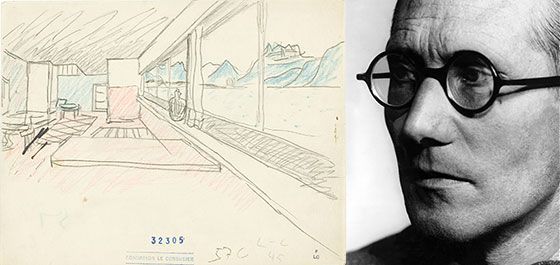

The show has some of its subjectÔÇÖs ┬¡passionate argumentativeness. Curator Jean-Louis Cohen builds a lawyerly case, backed up by paintings, reconstructed interiors, models, sketches, photographs, films, and plans. Yet what Cohen winds up demonstrating is that when ┬¡LeÔÇ»┬¡Corbusier looked at a cliff, a river, or a cityscape, what he saw was a formally satisfying setting for one of his creationsÔÇöor else a collection of what he called ÔÇ£brutal constraints.ÔÇØ The sketches he made during his early travels through Italy and Greece show that he absorbed the classical ethos: Architecture should dominate landscape. In a pair of 1911 watercolors, he depicted the Acropolis as a heroic forest of treelike columns with the sea and distant mountains rippling modestly in the background. His 1918 painting La Chemin├®e renders a white cube glowing like an ancient ruin, hinging ocher earth and lavender sky.

As a planner, he placed great faith in first impressions. He loved his idea of ┬¡Algiers as a white apparition nestled between the hills and the Mediterranean. He drew a plan for the R├¡o de la Plata region in Argentina as a quartet of small glowing tabs at the base of a great dark cliff. He liked New York best from the harbor; once he actually set foot on land, he found it chaotic and ┬¡inhuman. What repelled Le┬áCorbusier about actual cities were the ganglia of streets, the encrustation of experience and improvisation, the perpetual mixture of novelty and obsolescenceÔÇöwhat most of us now think of as their essence.

Projected on the wall in one of the galleries is a film of one of his ruthlessly totalitarian lectures. With a stroke of a Sharpie, he runs a roadway through the ground floors of apartment buildings raised on columns. The lines represent abstractions of speed and convenience, not fumes, noise, traffic, or vibrations. In the same talk, he articulates the ideal proportions of a civilized urban plan: 12 percent buildings, 88 percent open spaceÔÇöroughly the ratios that builders of high-rise housing projects followed. It is those orderly grids of X-shaped towers set on billiard tables of greenery that come the closest to embodying LeÔÇ»CorbusierÔÇÖs visionÔÇöand American cities that adopted it have been regretting it ever since.

So long as he was working on a domestic scale, he was an architect of dazzling sensitivity. He had an intuitive sense for how it feels to pass through a sequence of airy rooms, how light inhabits a home, how a concrete building can feel simultaneously muscular and feathery, how simple geometric forms can merge into lyrical counterpoint. The Villa Savoye, his early house in a suburb of Paris, is the work of a man for whom modern architecture was not a doctrine but a natural artistic expression. Its two slices of white concrete, sandwiching an almost continuous band of windows and resting on two sets of slim pilotis, make up a masterwork of humane modernism. In 1929, it offered a fresh, uncluttered kind of life, the luxury of the simple object perfectly placed in a verdant enclosure.

Yet the larger his ambitions were, the more lunatic his zeal. He resented reality and fumed when authorities lacked the courage to let him eviscerate their capitals. Somehow, though, that reluctance also goaded him. His ­famous plan for Paris was a fantasy, not a practical scheme: Since nobody was going to permit him to execute it anyway, he could be as visionary and violent as he pleased.

*This article originally appeared in the June 17, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.