I’m not a businessman / I’m a business, man!

—“Diamonds From Sierra Leone”

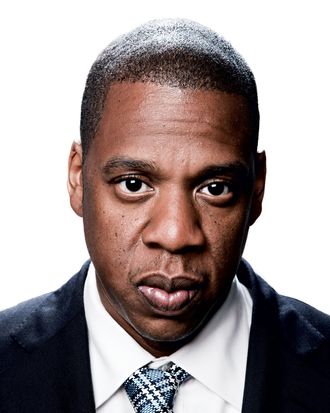

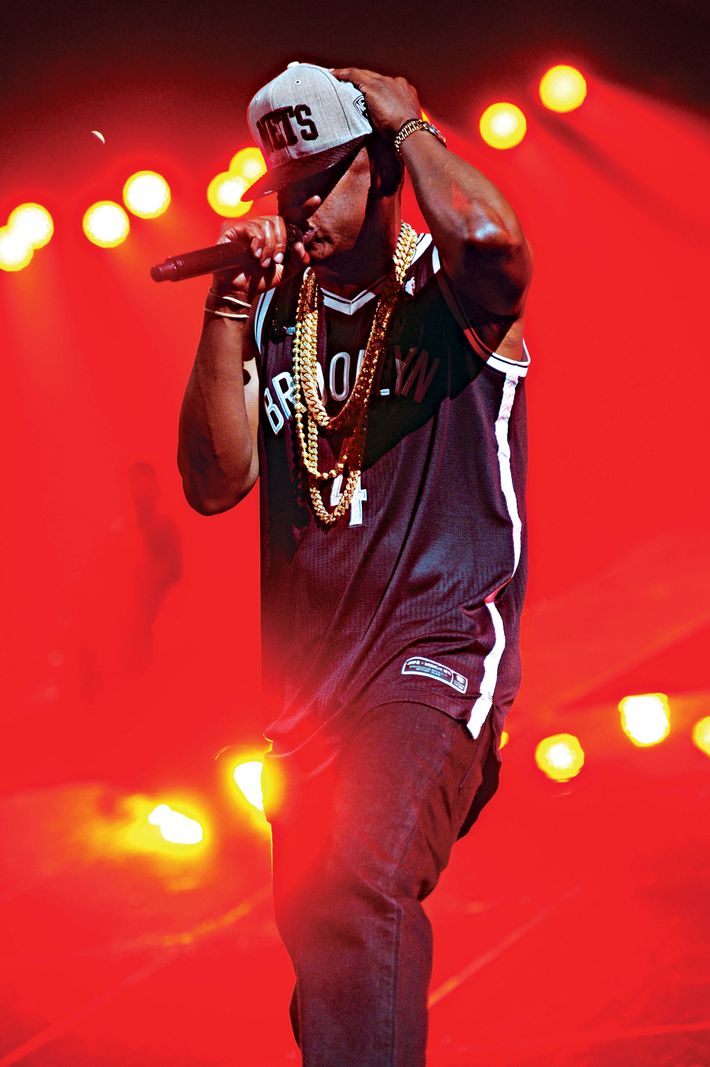

Last week, the twelfth solo studio album by the rapper Jay-Z, Magna Carta … Holy Grail, burst forth from a cloud of calculated obfuscation. The release came with little of the usual promotional buildup: no radio single, no Rolling Stone cover. Instead, it was announced via a three-minute commercial during game five of the NBA Finals. Shot in vérité style, the ad purported to show the artist in his studio, his Brooklyn Nets cap slung backward, as he made gnomic pronouncements to producers Timbaland, Pharrell Williams, Swizz Beatz, and the graybeard Rick Rubin. “We need to write the new rules,” Jay-Z declared.

The nature of those rules was revealed in the spot’s final second, when the words SAMSUNG GALAXY flashed on the screen. Viewers were directed to a website, where they could make out—amid stylized redactions—directions that allowed Samsung users to download a free app, which would in turn give them the album five days ahead of its general release. Samsung paid $5 each for a million digital copies, assuring the album of platinum status before it even appeared, while also giving Jay-Z the benefit of free advertising. The Wall Street Journal valued the partnership at $20 million—a figure that shocked an industry battered by piracy and declining revenues.

The deal was about much more, however, than solving a distribution problem. Before the release, the free app worked as a machine for data-mining and promotion, trading scraps of information, like lyric sheets and cover art, for access to users’ social networks. Though some critics objected to the crass intrusiveness—“If Jay-Z wants to know about my phone calls and e-mail accounts,” the Times’ Jon Pareles groused, “why doesn’t he join the National Security Agency?”—it didn’t much affect his standing with fans. A total of 1.2 million people downloaded the app, creating a mailing list at the very least and potentially offering something more, like the core audience for a music-streaming service.

“Jay-Z is bulletproof,” one prominent rock-band manager said with wonder two days after the commercial aired. “I don’t think anyone even cares how good his records are.”

In any event, the critical reception was lukewarm and the downloading process buggy. But that can subtract little from the legacy of Jay-Z the musician, a virtuoso whose evolution traces a broader societal progression. When he started out, his lyrics reflected a life not far removed from drug dealing. A few years ago, he and his wife, Beyoncé Knowles, were photographed in the White House Situation Room, with Jay-Z occupying the chair of President Obama, a fan. To a degree that rivals any entertainer, Jay-Z has managed to reconcile the dualities of black and white cultures, Bed-Stuy and Tribeca, art and commerce. There’s a reason why he likes to call himself, among many other things, J-Hova. But behind the bombast and heroic couplets, there is a man named Shawn Carter. His success is not just a metaphor: It is the product of a canny commercial intelligence.

Carter the businessman is working at a creative peak this summer. The new album is merely the loud opening salvo in an inescapable cross-promotional barrage. He’s headed out with Justin Timberlake on a fourteen-show tour promoted by Live Nation, his most important business partner. (He signed a $150 million deal, the largest of its kind, with the company in 2008.) Beyoncé is also touring in what she has titled, demurely, “The Mrs. Carter Show,” and headlining a Philadelphia music festival that her husband is curating for Budweiser. Meanwhile, the entertainment company Carter runs in partnership with Live Nation is launching a sports agency. The move, which required Carter to sell his interest in the Brooklyn Nets, is part of an ambitious diversification strategy that has shaken up the sports world.

Carter’s company, Roc Nation, already manages a stable of music clients, including Rihanna and M.I.A. It is the centerpiece of a portfolio that includes interests in technology (Powermat, a cell-phone-charging device made with Duracell), software (a video-sharing app called Viddy), real estate (small stakes in Barclays Center and the surrounding real-estate project), movie production (The Great Gatsby, a tale with a certain resonance), theater (Fela!), nightlife (the 40/40 Club, a high-end sports bar with locations in the Flatiron district and at the Nets arena), and apparel (in addition to Rocawear, the label he started and still endorses, he’s part of a joint venture that recently acquired half of Pharrell’s lines). A decade ago, Carter rapped that he wouldn’t rest until he was “the hundred million man.” Though a conclusive accounting is impossible, it seems certain he’s surpassed that figure, and on Magna Carta … Holy Grail, he sets a new goal: “Fuck it, I want a billion.”

While other rappers have made comparable fortunes—Dr. Dre, for instance, through his association with Beats headphones—no one rivals Jay-Z when it comes to synergies. In his new songs, he rhymes about the transactional mechanics of the Samsung deal (“A million sold before the album dropped”), boasts of signing sports stars like the NBA’s Kevin Durant and Yankee Robinson Cano, takes a swipe at the latter’s old agent (“Scott Boras, you over, baby”), and taunts those who suggest he overstated his ownership role in the Nets. “He made a song,” says Steve Stoute, his friend and partner in a marketing agency. “A businessman would have put out a press release.”

Before the album came out, Carter quietly attended a few public events, such as a benefit luncheon honoring Columbia Records executive Rob Stringer, who acknowledged him as “the guy from Samsung.” Once the downloading commenced, he emerged with a series of social-media stunts. He performed the same song for six hours at a Manhattan art gallery and took to his usually taciturn Twitter account for a lighthearted conversation with followers. But for the most part, he withheld himself from traditional publicity, marketing the album through a conversation about marketing. During the secretive rollout, Roc Nation publicist Jana Fleishman sent fans on scavenger hunts via photos posted to Instagram. One Sunday afternoon, she was sitting in front of a restaurant not far from her boss’s Tribeca condo, parceling out commemorative books and high-fives to anyone who said the password: “new rules.” The books contained song titles and lyric sheets that were covered with heavy black redactions, and offered little further information. This illustrates the first, and most fundamental, of Jay-Z’s rules: You must carefully manage your myth.

“The righteous seed in a hustler’s mentality was this: He wanted something more for himself.”

—Decoded

The scavenger hunt was not a new idea: Carter did something similar in 2010 to promote the release of his book Decoded. Spiegel & Grau had paid seven figures for the rights to the book, but the editor had only $50,000 budgeted for marketing. “I was shocked,” Carter’s longtime business manager John Meneilly told the authors of a Harvard Business School study. “I thought she was missing a couple of zeros.” So the imprint approached Droga5, an innovative advertising agency, which came up with the idea of hiding pages of the book all over the world. Fans could look for them via Bing, the new search engine from Microsoft, which covered the $2 million cost of the campaign. Even so, Carter insisted on approval of every detail, from the wording of clues to the size of Bing’s logo.

“Jay-Z is not just a billboard,” Meneilly told Microsoft. “We want creative control.”

Even after it was all put together, though, Decoded still left much unanswered. Structured around footnoted lyrics, it was an elliptical text. Much of it focused on what Carter called his “core story,” his first career as a drug dealer. “To this day people look at me and assume that I must not be serious on some level, that I must be playing some kind of joke on the world,” he writes. But if the middle-aged Yankees fans who sing along to “Empire State of Mind”—a crack-trade ballad—think it’s posturing or role play, Carter says they don’t understand him.

“I never had to reject Shawn Carter,” he writes, “to become Jay-Z.”

In fact, Carter really was a drug trafficker for a considerable period of time, and that was his formative business experience. When he was growing up in the eighties, crack merchants were the kings of his neighborhood. Carter fell in with a tough kid from across the hall, DeHaven Irby, who—he later rapped—“introduced me to the game.” He writes that he followed the drug market to Trenton, where Irby had family, and then Maryland. “One of the benefits of me and my crew working out of town was that I never had to be under the thumb of one of the big Brooklyn bosses,” Carter writes. “We were like pioneers on the frontier, staking out new territory where we could run things ourselves.”

The Maryland ring was based in Cambridge, a town of about 12,000 on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake. Irby allegedly ran cocaine down the I-95 corridor, supplying a ring of local distributors. The partners often cooked up the crack at a house on Robbins Street belonging to a man named Emory Jones. In Decoded, Carter recounts winter nights spent shivering in alleys, taking wrinkled bills from addicts.

In the song “99 Problems,” Carter describes a tense police stop—an incident that really happened, he claims, though he wasn’t traveling with a trunkful of cocaine, just a small sunroof-compartment’s worth. The cop let Carter go without a search. He was lucky: When Jones was apprehended in 1993, coming off a train from New York with 624 grams of coke, he ended up doing a year in a prison boot camp. Irby was also incarcerated for stints. Years later, he would release a series of YouTube videos claiming that he was the real kingpin of the operation and that Carter had merely appropriated. “He was there to see things, but doing some big-time Frank Lucas–type thing? No,” Irby told New York in 2007. “He nickeled and dimed, but nothing on a major scale.”

Whether or not he took poetic license, Carter’s involvement was deep enough to distract him from other opportunities. Since his teens, he had been circulating on the margins of hip-hop, rapping with small-time acts from his Brooklyn neighborhood and hanging in the entourage of Big Daddy Kane. D.J. Clark Kent, a performer who had a day job in the record business, recognized his skill as a rapper, but drugs were paying well enough that Carter wasn’t convinced that concentrating on music was worth his time.

“He said, ‘I’ll do it, but I ain’t putting up no money,’ ” Kent recalls. Just as he would later seek out Bing and Samsung to promote his book and his album, Carter wanted a partner who would bear the brunt of the upfront risk. “He was a hustler when I met him, and he’s a hustler now,” Kent says. “As the money changes, the elements within the hustle change.”

Kent introduced Carter to a Harlem promoter named Damon Dash, who arranged financing for his work. They recorded some songs but met with rejection from record executives. So they came up with a business plan and convened potential investors for a meeting in Harlem. “Jay-Z said to us that he had some ideas on how to make the brand bigger,” one attendee, Kareem “Biggs” Burke, told me. Carter talked about making music and clothing, staging live events, even building an amusement park. Burke was supportive, and eventually Dash and Carter asked him to join them in starting a music label, Roc-A-Fella Records. “I agreed and put up the money,” Burke wrote in an e-mail from a federal prison in Pennsylvania, where he is currently serving a five-year sentence for marijuana trafficking.

Carter says it was not until around the time he released his classic debut album, Reasonable Doubt, in 1996, that he “fully made the transition from one life to the next.” As it turned out, his career departure was well timed. An Eastern Shore drug dealer had begun working as an undercover informant, and in 1997, federal prosecutors indicted Irby, Jones, and a third defendant, alleging a seven-year conspiracy to develop “a massive consumer market” for cocaine. Irby fought the charges, and though no transcript of his 1999 trial is available, the first entry on a list of government exhibits was a picture of him, Jones, and an individual identified as “JZ.” (The picture was not preserved, and the prosecutor says she does not recall Carter’s name figuring in the case.) Irby was acquitted on technical grounds. But Jones had previously pleaded guilty and was sentenced to fifteen years.

Carter later wrote a song, “Do U Wanna Ride,” which began with a collect call from Jones in prison, and promised, “When you get home you know your spot’s reserved.” “We were together every single day,” Carter said in 2010 as he sat next to Warren Buffett for a joint interview conducted by Steve Forbes. “And had it not been for music taking me out at the right time, my life could have very easily been his.”

Own boss, own your masters, slaves / The mentality I carry with me to this very day

—“No Hook”

There’s a scene in The Big Payback, Dan Charnas’s wonderful history of the hip-hop business, that captures Roc-A-Fella’s early mentality. The three partners went to visit Kevin Liles, then an executive at the label Def Jam. To open the conversation, they presented him with a gift: a giant stack of cash.

“It was in a brown-paper bag,” Liles recalled recently. Today, his office is decorated with a version of the The Last Supper depicting Def Jam luminaries as the apostles; Jay-Z is Saint Andrew. Though Liles laughed off the bribe, he appreciated Carter’s sound and brought up a record contract. Carter had something else in mind. “He told me, ‘Why would I sign with you all?’ ” Liles said. “ ‘I’m Roc-A-Fella.’ ”

Just as Carter says he couldn’t work for the “Brooklyn bosses,” after Reasonable Doubt he was wary of signing a major-label deal—“the most contractually exploitative relationship you can have in America,” as he has described it—and his initial successes gave him leverage. Roc-A-Fella negotiated a joint-venture agreement with Def Jam, selling an equity stake but retaining a major degree of autonomy over production, A&R, and other creative functions. In exchange for splitting revenues, Roc-A-Fella gained a distribution platform. Carter put it to use, releasing seven studio albums in as many years. Burke told me that the Def Jam contract had performance bonuses built in. “They didn’t expect us to get so big,” he wrote. “By the time the formula kicked in we knocked it [out of] the park with Hard Knock Life. 5 million sold.” Jay-Z’s solo releases between 1997 and 2003 went on to sell 21 million copies.

Roc-A-Fella expanded by starting a clothing label, Rocawear. Although Jay-Z was the face of both companies, Dash was responsible for actually building them. A volcanic impresario, he padded the payroll with friends just out of prison, ran into continual trouble with women, and often barged around the offices trailed by a personal video crew. “When I wanted to create problems, I went to Damon,” says Lyor Cohen, the legendarily tough record executive who oversaw Def Jam. “And when I wanted to solve problems, I went to Jay.” But Dash had an ear—over Carter’s skepticism, he pushed the producer Kanye West out front as a performer—and an eye. He hired young graffiti artists to make Rocawear’s designs.

In 2003, Carter put out The Black Album, which supposedly marked his retirement from performing. The move was a feint, but it coincided with a more substantial break from his past. Def Jam had been acquired by Universal Music. When Cohen and Liles left for another company, they took much of the label’s upper echelon, and they also wanted to poach Jay-Z. Facing the loss of a marquee talent, Universal decided to exercise an option to buy out the remainder of Roc-A-Fella for $10 million. Carter could have resisted or departed, but Universal offered an enticing inducement to acquiesce: an agreement to eventually hand over all the rights to his master recordings, the most valuable intellectual property in the music business and a potential wellspring of residual revenue for an important artist.

“It was ownership,” Liles said, explaining his friend’s thought process. “ ‘Those are my words, my lyrics, my beats, and you mean I have the opportunity to own—not just partially own, but to own—and operate my creation?’ ”

The decision carried costs, however. It precipitated an ugly divorce from Dash, who was forced out of both Roc-A-Fella and Rocawear. Universal offered Carter the vacant presidency of its Def Jam subsidiary, but the prestigious title came with less power than it appeared. Def Jam was in dispirited shape when he took over, hollowed out by layoffs and defections. Carter found himself lording over a minor duchy in Universal’s entertainment empire. He discovered he had little patience for dealing with corporate hierarchy. Later, when Rolling Stone asked Carter if he recalled any meetings that left him frustrated, he replied: “Honestly? All of them.”

The label broke some major acts during Carter’s tenure, including Rihanna, but overall music revenues were declining as distribution moved online, and no one had any idea how to repair the model. When Carter produced his inevitable comeback record, its sales were disappointing, less than half of the 3.5 million copies he’d done with The Black Album. Meanwhile, Def Jam veterans like LL Cool J complained that he was too busy being a star to run the label. “It wasn’t his,” Liles said. “Jay operates best when it’s his.”

Word up on Madison Ave is I’m a cash cow / Word down on Wall Street homie you get the cash out

—“Operation Corporate Takeover”

Unpleasant as it may have been at times, the Def Jam job served Carter’s greater ambitions. This was a transitional period when both he and hip-hop were striving for respectability. The bloody era of Biggie and Tupac was still recent history, and Carter himself had been arrested for a vengeful stabbing in 1999. On The Black Album, though, he declared he was setting aside childish things—“I don’t wear jerseys, I’m 30-plus / Give me a crisp pair of jeans, nigga, button up”—and changed Rocawear’s look accordingly. (Despite staff anxiety, the upscale look sold even better, and revenues of Rocawear’s parent company rose 20 percent over the following three years.) The new style accorded with his broader conviction that his brand could carry power outside the niche euphemistically known as the “urban market.” But the route to the mainstream was nervously guarded by corporate executives. So Carter became one.

“Jay had the ability to transcend the artistic and land on being a lifestyle brand,” Steve Stoute said one morning as he sat deep in a plush couch in a skylit lair high above Times Square. Stoute, a former rap manager, is a guru for companies that want to acquire a touch of hip-hop credibility: On the table between us sat a double-magnum-size bottle with a label that matched the cover of his book on branding, The Tanning of America. In it he recounts how in 2000, he persuaded Jay-Z to mention Motorola’s two-way pager in a song, as a friendly favor. “The shared values of the brand,” Stoute wrote, “and a poet/entrepreneur/icon who stood for all that was real and possible, the coolest and most hopeful path of all, registered overnight with consumers.”

Today, Carter is a partner in Stoute’s firm, Translation, and he never drops a brand name so casually. Carter is intensely aware of the value of his association. Often he forms alliances with brands—HP, Bing, Samsung—that are trying to catch up to a market leader and are willing to pay a premium for his cool. The model for all of these deals is one that Stoute struck a decade ago with Reebok.

At the time, the sneaker company was lagging Nike and trying to cultivate a streetwise image. “He would never, for any amount of money, endorse Reebok,” Stoute said. “But what he would do is have Reebok be his partner in building the Jay-Z brand.” After painstaking negotiations, the two sides formed a joint venture to produce a sneaker, the S. Carter, modeled on a Gucci design favored by the hustlers of the eighties. Carter promoted it by sponsoring a team in the Rucker-playground summer league composed of ringers like Tracy McGrady and a teenage LeBron James. Carter also insisted that his deal include a television spot, which was hashed out at the 40/40 Club and shot to his exacting specifications.

There were limits to how much Carter would shill: Some Reebok executives were annoyed that he occasionally wore Nikes. 50 Cent, who had a lower-end line, was always in Reeboks, and actually ended up making more from his endorsement deal than Carter, who shared in the joint venture’s overhead costs. “Even if it did cost him some money in the short term,” says Que Gaskins, who oversaw the sneaker’s marketing as an executive at Reebok, “I think it was really important to him to be perceived as an equal partner.”

The Reebok deal led to relationships with other major corporations, alliances that often came with an equity stake, an impressive title—“co–brand director, Budweiser Select”—or an advertising campaign timed for Jay-Z’s purposes. He also began seeding his songs with placements for products like the Champagne Armand de Brignac, the cognac D’Usse, and even a beauty-product company called Carol’s Daughter—all enterprises in which he had a disclosed or presumed interest. Stoute once tried to market a trademarked color, “Jay-Z Blue.” That didn’t work, but you might say Carter and his wife have since relaunched it as a diffusion brand. Earlier this year, they trademarked their daughter’s name, Blue Ivy Carter, for the purpose of marketing products like baby strollers, bibs, and teething rings. The name Shawn Carter, meanwhile, was licensed in perpetuity to a joint venture Carter formed with a publicly traded clothing company in 2007.

Some brand associations reap intangible dividends, like Carter’s relationship with the Nets, an investment that was both less and more than met the eye. At a Barclays Center concert last year, Carter gave a lengthy monologue about the origins of the deal: how Jason Kidd—then the New Jersey Nets’ point guard, now the coach—told him one night in 2003 that the team was for sale, which led to a series of meetings with developer Bruce Ratner, who was bidding to buy the team. “He was like, We’re going to Brooklyn,” Carter told the crowd. “I was like, Oh, let’s do that. I actually said, ‘Fuck yeah.’ ”

Minus the profane flourish, that’s pretty much how it happened in Ratner’s recollection. The developer took Carter to the top of a tall building overlooking the state-owned rail yards along Atlantic Avenue, a prime expanse of Brooklyn real estate.* He feared he might lose the Atlantic Yards site if the government went to open bidding, so he had come up with the Nets as a unique anchor tenant. Carter pointed out a nearby building where he had once lived, 560 State Street—later to be immortalized as his “stash spot” on “Empire State of Mind.” “I don’t think I overly thought about, at that point, whether he had good business sense,” Ratner told me. “But I did know this: I knew his history, I knew how he started from nothing.”

Some discerned a political calculus: Ratner was facing a tough public-approval process. “He was kind of their minority poster child,” says L. Londell McMillan, who knew Carter growing up in the projects and went on to become an entertainment attorney and a fellow Nets investor. He added, “You look at his business model, it is very similar to Magic Johnson’s.” In fact, before sealing the deal with Carter, Ratner unsuccessfully wooed Johnson. “I think there was some skepticism,” says one executive who was involved in the project. “Could this guy who was a rough teenager and committed acts of crime, who had these horrible lyrics, come into the corporate fold?”

For Carter, the deal was all about changing perceptions—and making connections. Drew Katz, whose father Lewis was selling the team to Ratner but was planning to hold on to a percentage, helped to broker an initial meeting at the 40/40 Club. “My dad said, ‘Being a partner with Bruce and me, you’ll learn a whole lot more about how to make money,’ ” Katz recalls. “Both sides were trying to feel each other out to see who was going to get the bigger benefit of being connected.” Carter’s investment of a million dollars amounted to one third of one percent of the $300 million purchase of the team and allotted him a similar interest in the planned arena and the rest of the Atlantic Yards real estate. Those numbers weren’t publicized, however, and Carter was presented as a major partner.

At the 2010 ground breaking for Barclays Center, Carter was one of a handful of hard-hatted executives holding shovels. Marty Markowitz, Brooklyn’s blustery borough president, praised him as an entrepreneur who “went from bricks to billboards,” a reference that caused Carter to arch his eyebrows theatrically. Alone among the well over 100 limited partners, Carter had a seat on the arena’s board. “Everyone quieted down when he spoke about anything that had to do with marketing,” Ratner said. The team awarded an advertising contract to Translation. As it prepared for the relocation to Brooklyn, Carter exercised influence over the new logo and color scheme.

There were tensions, particularly during the messy period when Ratner was slashing payroll and struggling to move the team. When naming rights became available for the Meadowlands arena where the Nets played, Carter wanted to rename it “the Roc,” for Rocawear, and he made his displeasure known when he was outbid by Izod. Carter wanted to use his connections to improve the team, but there were limits to what he could do. Many fans hoped he would recruit the biggest pending free agent of all, LeBron James, but he was wary of asking his buddy to come to a losing team. “We’re friends—we’ve still gotta hang out!” Carter told Rolling Stone. James ultimately did grant the Nets an audience, but opted for the Miami Heat. It seems there are no hard feelings: The two superstars host an annual “Two Kings Dinner” for charity during the NBA All-Star break.

Martin had a dream, HOV got a team

—“F.U.T.W.”

The James relationship is emblematic of the way Carter approaches life: His friendships and investments interweave into one very expensive tapestry. “Over time I’ve developed a clearer sense of the difference between business ‘friendships’ and true friendships,” he writes in Decoded. “Loyalty is what sets them apart.” A few of his top executives—like Briant “Bee-High” Biggs, a cousin who has been exploring technology investments in Nigeria, and Tyran “Ty-Ty” Smith, who is ever at his side as a sort of homeboy without portfolio—are confidants from his life before music. Many others date back to the days of Roc-A-Fella.

During his period as Def Jam’s president, Carter found himself in an unaccustomed position, working for a large, unfriendly organization. He tried to sell the higher-ups at Universal on giving him his own vehicle, a fund to invest broadly in entertainment ventures. They passed, and also balked at his contract demands, so he announced his departure in 2007, taking his core team en masse. After a whirling period of free agency, he signed his $150 million deal with Live Nation, the publicly traded concert promoter. One third of the money went to start Roc Nation, the entertainment company he wanted—a boutique firm that capitalizes on Carter’s ability to forge alliances with much larger partners.

At the time, Live Nation was trying to diversify by forming comprehensive “360 deals” with major stars. The rest of the $150 million, a mix of upfront payments and advances, gave the company rights to Carter’s tours, recorded music, and other revenues. For Carter, the deal was appealing because it locked in future profits. For Live Nation, the benefits were less evident: Kenny Chesney sells out football stadiums; the biggest hip-hop acts play arenas.

Last year, Carter toured Europe with Kanye West and staged a celebratory solo stand in Brooklyn to open up Barclays Center. The eight sold-out shows grossed around $7.3 million, according to the trade publication Pollstar. Before the finale, Carter and his entourage caught the subway at Canal Street and rode to Brooklyn, creating a viral-video moment. Walking next to him was a middle-aged man in a Nets cap: his old friend Emory Jones. When Jones was up for a sentence reduction in 2009, Carter wrote a letter to the judge, and on his release there was reportedly a Maybach waiting at the gates. “Welcome home to Emory,” Carter raps on the new album. “Let’s get back to this dinero.”

That night, Carter took the stage in full Nets regalia, in a mood to redress some grievances. A recent front-page New York Times story had revealed that the current size of his ownership stake was just one fifteenth of one percent. “Most media, they try to refer to my participation in the team, they talk these numbers, ‘.0015’—whatever. I don’t know where they get that number from, but hey, that’s their way of diminishing our accomplishments,” Carter said. Then, after referencing his hard-knock childhood, he declared: “I stand before you as an owner of the Brooklyn Nets.” He called on the audience to raise their middle fingers, and launched into “99 Problems.”

The origin of Carter’s diatribe was a change in his business relationship with the Nets. In 2008, after years of lawsuits and delays, the crash hit, scuttling Ratner’s bond financing. As he was about to lose the site, Ratner called on an unlikely savior, the Russian nickel billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov, who invested $200 million in cash and took on a similar amount of debt. Carter, like all the limited partners, saw his equity in the team diluted by 80 percent. It wasn’t just the proportions that changed, though. “Bruce was a pretty egoless owner,” Drew Katz said. The same could not be said for Prokhorov, an international playboy who recently ran for Russia’s presidency.

Nonetheless, Carter made the most of his role as the revived franchise’s most visible fan. He put a branch of the 40/40 Club on the luxury-suite level of Barclays Center. (On the less exalted concourse, his cousin also opened a chicken-wing concession.) Carter applied his expertise to the Vault, the ultraexclusive luxury-suite complex on the court level. “Jay-Z looks at the design,” Ratner recalls, “and he says, ‘Nope!’ ” Carter had a suite in the Vault, and he often sat with members of his inner council in a row of courtside seats just left of the Nets bench.

As always, Carter exploited the marketing opportunities. During the Nets’ first regular-season home game, for instance, he wore a conspicuous pair of custom-retrofitted Air Jordans, overlaid with nine different animal skins. The exposure of the “Brooklyn Zoo” shoes, which retailed for $2,500, provided a major boost to PMK Customs, the Cleveland firm that designed them. It is now consulting with Puma and Under Armour, says André Scott, the company’s chief executive. Scott told me his sneakers caught Jay-Z’s attention through Emory Jones, who, getting back to the dinero, had previously acquired part of PMK Customs.

Carter wasn’t just there to be seen, though: He is a genuine fan. “He appears to be absolutely thrilled and enthralled with the game,” says David Kuperberg, a real-estate executive and Nets investor who has seats behind Carter’s. He isn’t an obnoxious partisan like Spike Lee. “The opposing players are always saying hello to him,” Kuperberg says. As it turned out, Carter wasn’t just being friendly. He was networking.

I’m on to the next one / On to the next one / I’m on to the next one

—“On to the Next One”

Jay-Z’s chorus blasted over Barclays Center’s sound system as David Stern prepared to announce the next pick in the NBA draft. Carter himself was nowhere to be seen, but it was still very much his building. His presence hung in the air as prospects waited in a corral ringed with cameras, families and agents at their sides. The agents were easy to identify—they were the white guys—and they had reason to be nervous. A few days before, Carter had become licensed to represent NBA players, and now he was free to come after their clients.

The launch of Roc Nation Sports was orchestrated through the usual social-media striptease. One day in early April, Roc Nation and CAA announced they were forming a partnership to start the agency and stealing Robinson Cano from powerhouse Scott Boras. As an opening statement, it was like picking a fight with the biggest guy in prison. Cano tweeted out a picture with Carter and the message “Rocboys!” Over the ensuing weeks, further clues leaked: A picture of Carter with the Jets’ rookie quarterback Geno Smith appeared on Instagram, as did one of the WNBA player Skylar Diggins standing next to a gift from the agency, a white Mercedes. Then, moments after game seven of the NBA Finals ended, Roc Nation executive Rich Kleiman tweeted: “Everything starts Now.” A few days later, Kevin Durant posted an Instagram photo of himself and Carter signing a contract, with the hashtag #newrules.

If the promotional connection between the agency and the new album might seem tenuous, it made sense to one audience: professional athletes. The night the Samsung ad ran during the NBA Finals, C. J. McCollum, a guard who was expected to be picked high in the draft, sent out a tweet marveling that Jay-Z had “managed to pitch his album and was probably paid by Galaxy too.” At an interview session the day before the draft, McCollum and other touted prospects spoke admiringly of Carter’s marketing savvy. “It’s Jay-Z!” said Ben McLemore, who was wooed by Roc Nation, as was Nerlens Noel, thought by many to be the draft’s top talent. Last week, reports linked Carter to two baseball phenoms, Yasiel Puig and Yoenis Cespedes. In a radio interview, Carter said he was seeking to get clients “their just due,” as opposed to “half-ass agents or people who rob them.”

Sports agents are a paranoid bunch, always on guard against rivals, but Carter’s entry into the business has incited a different order of hysteria. “Guys are just going to Jay-Z because they fetishize him,” said one agent. “It’s getting crazy.” Some were fighting covertly, pressing the NFL Players Association to look into whether Carter’s courting of Geno Smith violated a technical regulation. On the new album, Jay-Z responds: “NFL investigations / Oh, don’t make me laugh.”

As it is, the agency business is roiling, with big firms squeezing embattled boutiques. Carter aligned himself with one of the giants. He has a long-standing relationship with CAA agent William Wesley, a shadowy fixer who used to play gatekeeper to LeBron James. But James left CAA last year. Carter will function as a new rainmaker, bringing in lucrative talent like Durant. In return, Carter gets a partner that will presumably defray his start-up costs and provide negotiating expertise. Fees for playing contracts are set fairly modestly: usually between 3 and 5 percent. The cut from marketing deals is considerably higher, and that will be where Carter concentrates his efforts.

After Cano’s signing, rumors circulated around baseball of exorbitant endorsement promises, and many experienced agents question whether Roc Nation will be able to deliver. Cano’s upcoming free agency will be closely watched. “In baseball, in the owner’s game of player contracts, it’s about what you know, not who knows you,” Boras said. “Fame plays no part.” Other agents asked whether Carter was prepared for the recruiting corruption and grasping families, the 24-hour demands of client service.

“Is anyone asking why Jay-Z wants to be a sports agent?” asked one. “Does he need to create new income or was he just tired of owning his 0.000002 percent of the Nets?”

Throughout his career, though, Carter has shown he knows when to leave the stage. His deal with Live Nation, in early 2008, was timed for the peak of heedless deal-making on Wall Street. Within months, the Live Nation executive who championed the 360 concept was forced out. “They didn’t get much out of it,” says Rich Tullo, director of research at Albert Fried & Company. “That’s why they don’t do those deals anymore.” Similarly, in 2007, Carter sold Rocawear’s trademark and licensing rights for $200 million in cash, split among three partners, to the public company Iconix. The recession sapped Rocawear’s sales, and analysts now see the label as an overpriced acquisition.

The Nets should be contenders next year, but the team’s aging core looks uncertain beyond that, and after the climax of the inaugural season, the relationship was bound to pay diminishing returns. Carter could call himself an owner, but he could never really control the team. So he left to a triumphal tune, waving a Mutombo-esque finger on a song: “Would’ve brought the Nets to Brooklyn for free / Except I made millions off it, you fuckin’ dweeb.”

There was much speculation about the identity of the “dweeb,” but Ratner says Carter assured him he wasn’t the target. He says he was “surprised” by Carter’s decision, but they talked it out. “It’s part of a bigger business plan,” Ratner says. “Jay-Z sees that the important thing in the world today is content. And content means everything from stuff that’s presented at the arena to sports in particular to sports on TV.”

Sports leagues are legalized cartels with controls on compensation. But there are many other ways to profit from athletes. Iconix has been hinting about “new exciting initiatives” to revive Rocawear, and there are market rumors about a sportswear line. TV networks, in search of content that can’t easily be fast-forwarded, have been showering even marginal sports like soccer with cash, creating a boom economy. Kevin Liles, who watched game seven of the NBA Finals with Carter, told me that if I wanted an idea of what his friend has planned for his sports clients, I should look at the equity-driven deals he’s negotiated for himself. “Sports is just another piece of a portfolio that he’s building to curate culture, to challenge the status quo,” he said. “Why can’t they start to make different demands in the sports business?”

Carter likes to call himself “the new Sinatra,” but even the original Chairman of the Board wasn’t able to sustain his cultural relevance forever. Sooner or later, everyone ends up singing at the Sands. No Jay-Z album over the past decade has come close to selling like those at his peak (and neither, likely, will Magna Carta). Though this is certainly not how Carter would characterize it, the move to build a diversified entertainment company at once hedges a risk—the natural decay of Jay-Z, middle-aged megastar—and capitalizes on skill set: Carter’s ability to spot, cultivate, and exploit talent.

“Jay-Z has, in my view from the outside, figured it out: how the sports and entertainment business has changed and merged,” says Mark Rosentraub, a University of Michigan professor and co-author of the book Sports Finance and Management. “It’s no longer about the team on the field; it’s really about the real estate and entertainment that swirls around it.”

Carter is retaining his interests in the Atlantic Yards real estate, and he and Ratner are now seeking to expand their partnership further, by advancing a proposal to renovate the Nassau Coliseum. In early May, several teams of bidders gathered at a police station in Mineola to present their plans to an advisory council. Rosentraub, a consultant to a competing team, gave a sober presentation of financial projections. Ratner’s group, meanwhile, brought in a surprise guest, who inspired a cascade of flashbulbs when he entered, fashionably late, in the midst of a speech.

“Did I break your train of thought?” asked Carter, dressed in a conservative white shirt and black V-neck sweater. The meeting halted so he could shake hands with members of the council. He took a seat next to Ratner and sat silently, absorbing the room’s attention, as the team presented architectural renderings. When the presentation was over, he lingered for a moment so Nassau County executive Ed Mangano could get a joint photo.

“We may have 99 problems,” the politician said, “but the coliseum’s not one of them.”

Carter gave him an obliging laugh.

“That’s not bad,” he said. “The president used that line.”

*This article originally appeared in the July 22, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been corrected to show that the state-owned rail yards Bruce Ratner redeveloped were part of a larger real estate project called Atlantic Yards.