A few years ago, Sting found himself in a position that was unique to his experience, though perhaps familiar to certain others: He had grown sick and tired of Sting. For three decades, Sting had been not just one of the world’s most famous musicians but one of its preeminent musical confessors: a singer-songwriter who, through all of his incarnations—spiky white reggae man, stadium rock star, sleek fixture of adult-contemporary radio—had kept the music coming by, he says, “scraping the barrel of my soul.” The result was a prolific output: five LPs with the Police and a string of hit solo albums, a run that concluded in 2003 with his eighth solo release, Sacred Love. Then, abruptly, the songs stopped. Sting has released three albums in the years since, all on the classical label Deutsche Grammophon; none were pop records, per se, and none included new songs written by Sting. Eventually, he realized he was blocked.

“I thought: Maybe I’ve lost my mojo to write,” Sting recalls. “There’s a lot of self-obsession involved in being a singer-songwriter. I’d gotten sick of navel-gazing. I’d gotten sick of putting myself on the couch.”

Sting wasn’t on the couch when he sat for an interview one afternoon this past June. In fact, he was on the table: He’d helped himself to a seat on top of a big wooden coffee table, in a plushly appointed room on an upper floor of his record label’s midtown headquarters. He was there to discuss the project that had pulled him out of the songwriting doldrums: a musical set in the eighties about the decline of the shipbuilding industry in his hometown of Newcastle, England. The show, The Last Ship, has songs by Sting and a book co-written by John Logan and Brian Yorkey; it’s slated to reach Broadway in the autumn of 2014, in a production directed by Joe Mantello (Wicked). In the meantime, we have an album also titled The Last Ship, Sting’s first original music in a decade, a selection of songs written not for Sting himself but for the play. “Once I came up with these characters, the songs began to pour out,” Sting says. “It was such a relief not to write about myself. I had to get myself out of the way.”

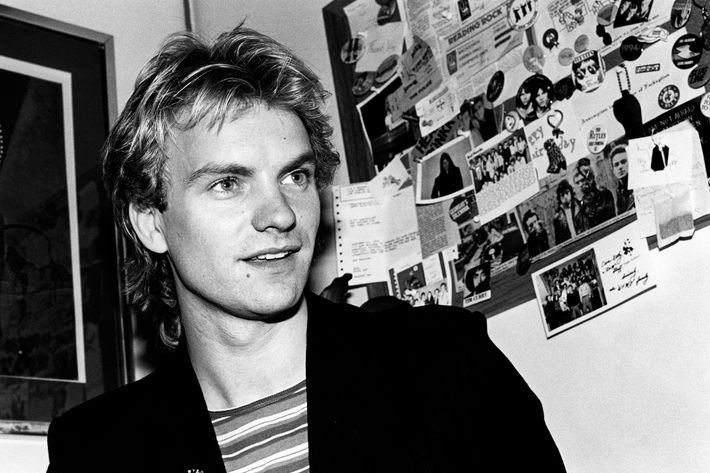

In person, the first thing you notice about Sting is how familiarly—almost laughably—Stingish he looks. His eyes are greenish-blue; when he shakes your hand, he fixes you with a gaze that can only be called steely. He wears tight-fitting jeans and a sweater and is as svelte and toned as a man a third his age—a walking advertisement for yoga and good eating and Tantric sex and whatever other benefits accrue from the lifestyle of a multimillionaire with homes in Manhattan, London, Malibu, the English countryside, and Tuscany. In “I Love Her But She Loves Someone Else,” a dusky ballad on The Last Ship, Sting sings in the voice of a man contemplating the ravages of time in the bathroom mirror: “When a man of my age shaves his face in the morning / Who is it that stares back and greets him? / The ghost of his father long dead all these years? / Or the boy that he was, still wet in the ears?” At 61, Sting’s face has gotten fleshier; his hairline has moved back a few inches, and he wears it buzzed close to the scalp. But you’d be hard-pressed to find a better-looking, balding sexagenarian. “I do like to keep fit,” he says. “It’s vanity.”

Vanity, of course, is a charge that has often been leveled at Sting. It’s a strange thing to criticize a pop star for, but Sting has long provoked strong animosity, especially among tastemakers and the self-consciously hip. The Last Ship is unlikely to sway the Sting-haters. The show doesn’t hide its Brecht-Weill aspirations. It’s an allegory about deindustrialization: the story of workers who occupy their shipyard, which the government has ordered closed, and build one last ship for their own use. “It’s a crazy idea for a story, really,” Sting says. “A quixotic, even Homeric idea.”

The music, meanwhile, veers far from rock and pop. The songs are steeped in the folk sounds of Northeastern England, with its rich weave of Celtic influences. Sting sings several numbers in a thick Northumbrian burr. The instrumentation is regional, too, with many songs anchored by tooting Northumbrian pipes and melodeon, a button accordion frequently found in folk music of the British Isles. There are waltzes, reels, sing-alongs that lurch and thump like sea shanties. But there’s also urbanity in the music: dashes of bossa nova and lots of Broadway, the lush chromaticism of Gershwin and Rodgers and Sondheim.

“If you scratch me, I start singing show tunes,” Sting says. “I’m singing the whole of Carousel, the whole of Oklahoma. I love My Fair Lady. I love South Pacific, West Side Story.”

Sting’s Last Ship show tunes include some music that stands with the best of his career. There’s the gorgeous “August Winds,” which swoons and sways over fingerpicked guitar. There’s “Practical Arrangement,” a heartbreaking marriage proposal from a man in love to a woman who doesn’t return the feeling. The title track is a waltz that stirs biblical references and images of apocalypse into the tale of a ship’s launching: “Oh, the roar of the chains and the cracking of timbers / The noise at the end of the world in your ears / As a mountain of steel makes its way to the sea.”

In that song, as elsewhere on The Last Ship, Sting plays to type. He has never been shy about his ambitions, nor reluctant to flaunt his book-learning. Today, some of Sting’s loftier songs plays like self-parody: The Jungian Cliff’s Notes in “Synchronicity” (1983), the portentous Cold War anthem “Russians” (1985), with its musical quotations from Prokofiev and groaning lyrical platitudes (“We share the same biology / Regardless of ideology”). There are songs on The Last Ship that will incite the usual complaints: Sting is pretentious, he’s a show-off, he burdens his songs with ideas that are too weighty — and with ideas that aren’t as weighty as he supposes.

Certainly, Sting has had his pseudy moments. (All together now: “You consider me the young apprentice / Caught between the Scylla and Charybdis.”) But he has also been subject to a special kind of philistinism often directed at popular musicians, who are expected to stick to “basics” and punished when they get above their station, or let on that they may have read a book. “I think there’s an idea pop singers should be idiot savants, and not just savants,” Sting says. “They’re easier to control that way.”

Another frequent complaint is that Sting is a milquetoast, that the vaguely punky reggae-pop adept of the Police’s early albums has devolved into a purveyor of bland, easy-listening music with hoity-toity-jazz and world-music airs. This criticism, too, is rooted in ideology, in rock culture’s preference for “raw” sounds and a knee-jerk reaction to music that prizes other qualities: sophistication, gentility, beauty. There’s no doubting Sting’s gifts. Listen back to his solo albums, from The Dream of the Blue Turtles (1985) to the R&B-inflected Sacred Love to Songs From the Labyrinth, his 2006 tribute to the music of Renaissance composer John Dowland, for which Sting learned to play the lute. You’ll hear the work of a guy who, whatever his weaknesses, is a lavishly gifted tune-crafter and a musician with fearsome chops.

Those qualities are much in evidence on The Last Ship. The theater suits Sting: The artifice of the show-tune form is a good match for his slightly stiff, self-consciously heady mix of words and music. And while the project jolted him out of his confessional songwriter’s funk, The Last Ship may in fact be his most personal record. Growing up on the north bank on the River Tyne, Sting watched huge vessels slowly rising over the shipyard at the end of his street, blotting out the sun. His grandfather was a shipwright; most of his neighbors worked in the shipbuilding trade.

“There was the shipyard at one end of the town and the coal mine at the other,” he says. “There wasn’t really much clue about how you would make a living if you didn’t want to join those two industries. I didn’t. Education and music became my escape. And then, in the eighties, everything shut down. I’ve carried survivor’s guilt ever since.”

You can hear that drama play out in the ballad “Dead Man’s Boots,” a wrenching dialogue between a shipyard worker and his son. It’s as touching a song as any Sting has recorded, but it’s not the sort of thing that will find its way onto a radio playlist.

“It’s unlikely, I think, that I’ll ever have a big hit again,” Sting says. “If I wanted a hit, though, I’d want to have one against the odds. I’d want it to be a song that doesn’t obey the formula.”

Sting himself may have vanished from the top of the pops, but the same can’t be said for Stingism. In recent years, the Zeitgeist has circled back to him. It may be that the Police’s 2007–08 reunion tour, one of the highest grossing in history, brought his music back into earshot. It may simply be a matter of pop culture’s cyclically shifting tides of nostalgia and reappraisal. Has Sting gotten so uncool that he’s cool again?

Today, a younger musical generation is embracing him as a kind of hip granddad. Maroon 5 have squeezed a bunch of hits out of Adam Levine’s sub-Sting croon, and they made the connection explicit with the Police-style, reggae-pop smash “One More Night,” which topped the Billboard Hot 100 for nine weeks in 2012. Just three weeks after “One More Night” ended its run came another, even more flamingly Police-inspired No. 1 hit, Bruno Mars’s “Locked Out of Heaven.” In February, at the Grammy ceremony in Los Angeles, Sting joined Mars, Rihanna, and two of Bob Marley’s sons, Ziggy and Damian, for a medley of “Locked Out of Heaven,” the Police’s “Walking on the Moon,” and Marley’s “Could You Be Loved.” Sting says: “In rehearsal, I was thinking, This is a mistake, trading high C’s with musicians who could be my children.”

In fact, it turned out to be the highlight of the Grammys show, with Mars’s hopped-up soul revue-style backing band careening all over the place, and Rihanna in unusually fine form, sounding nearly as good as she looked. But it was the elder statesman, planted in front of a microphone stand with his bass, who commanded the stage. Sting’s high, bright, cutting singing voice is one of pop’s most distinctive, instantly recognizable instruments. In 2013, that voice is as powerful as ever, and more dexterous; Sting has evidently lost nothing of his signature top-end, and he has developed a burly lower register, which rolls out, in a dark, sea-weathered tone, in several of the ballads on The Last Ship. A voice like his is one of pop music’s holy grails: an indelible sonic signature, a thing that can’t be learned or faked or — despite Adam Levine’s best efforts — mimicked.

“If you have a recognizable sound — a vocal fingerprint, if you like — that’s an X-factor,” Sting says. “It’s not about whether it’s good or bad, ultimately. It’s how identifiable and unique it is. People may love what they hear or hate what they hear — and all the gradations in between. But they’ll always know it’s you.”