It was a Sunday afternoon in February, and the Fashion Police writers had taken their seats around the large wooden dining-room table in the Pacific Palisades home of Melissa Rivers, the showÔÇÖs executive producer. Her mother, Joan Rivers, lords over these four-to-five-hour joke fests, during which each writer pitches snarky celebrity-fashion dos and donÔÇÖts that theyÔÇÖve spent the past few days crafting. Joan laughs at the funny ones and politely passes over the others; eventually a handful of one-liners will be selected, many of which Joan will tweak and deliver, improvlike, on-camera (ÔÇ£[Jennifer Lawrence] called me, she said she was so embarrassed that she had fallen, and I said, ÔÇÿRelax my darling, itÔÇÖs not the first time a girl got on all fours on her way to getting an OscarÔÇÖÔÇàÔÇØ).

But during this particular meeting last February, the writers had other business to discuss, chiefly their bid to join the Writers Guild of America, West, a union that ┬¡represents Hollywood writers. With Guild membership comes higher pay and benefits, and Rivers is a member of the East Coast branch. So far, the writers were running up against resistance from E! They figured that if they could just get the support of Joan Rivers herselfÔÇöthe seriesÔÇÖ starÔÇötheyÔÇÖd have the leg up they needed.

Ned Rice, a veteran comedy writer who had been with the show since 2010, spoke first: ÔÇ£Joan, before we pitch our jokes, we want to talk to you about the Guild situation.ÔÇØ But before he could continue, Rivers threw her fists down on the table and launched into what the writers describe as a tear-filled tirade that ranged from sarcastic (ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve gained four pounds over thisÔÇØ) to threatening (ÔÇ£The network said I could have a contract, but I can only keep four of you. DonÔÇÖt make me chooseÔÇöI canÔÇÖt choose!ÔÇØ). Even Melissa began yelling: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve given the WGA everything but a kidney!ÔÇØ

After five minutes, Rice walked out. ÔÇ£If anybody else wants to have your little Norma Rae moment, go right ahead,ÔÇØ Rivers reportedly told the group. When writer Michael Prescott explained that Rice had been speaking on behalf of all of them, Rivers pointed at him from the across the table and called him a ÔÇ£fucking asshole.ÔÇØ

Eventually, head writer Tony Tripoli cut in: ÔÇ£All right, letÔÇÖs make jokes about celebrities.ÔÇØ With that, they all went back to work.

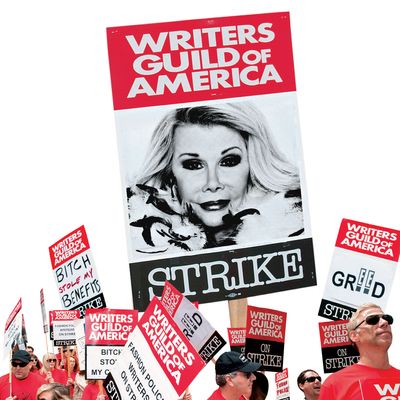

Four days after their confrontational meeting with RiversÔÇöwhich the writers dubbed ÔÇ£Black SundayÔÇØÔÇöthe Writers Guild filed an unfair-labor-practices charge. Three days later, the writers showed up to the Fashion Police Oscars meeting wearing red Writers Guild T-shirts. And two months after that, on April 17, the ┬¡majority of the writers went on strike. Since then, Fashion Police has replaced them and been airing new episodes. In response, the striking writers held a 150-┬¡person-strong protest outside E! headquarters in Los Angeles where they chanted, recycling RiversÔÇÖs famous catchphrase: ÔÇ£Joan Rivers, can we talk?ÔÇØ

Fashion Police has been on the air for three years and boasts viewer numbers equal to, if not more than, that of two other popular E! programs, The Soup and Chelsea Lately. Most of the writers were never officially hired to work on the show. In fact, the network considered only two writers to be on staff; the other ten were part-time. But as each writer was called in week after week, the job required a bigger commitment. Their weekly assignment was to create up to 200 jokes eachÔÇötwenty celebrity photos, eight to ten jokes per shotÔÇöwhich, according to writers, could take up to 35 hours a week, not including the writing marathons required for specials that follow the Oscars or Grammys. Most were paid $610 per week, and at least one writer with a few more decades of experience was getting $1,750 (a WGA contract would secure them $3,000 to $3,900 per episode).

While major network talk showsÔÇöincluding Fallon, Letterman, and ┬¡KimmelÔÇöare covered by the WGA, itÔÇÖs not uncommon for cable talk shows to start out nonunion. When Hugh Fink, a veteran comedy writer and producer who wrote for Saturday Night Live and Craig Ferguson, created The Showbiz Show With David Spade on Comedy Central in 2005, he requested that the show have a WGA contract. ÔÇ£[Comedy Central] said, ÔÇÿIf you want us to do your show, you can either do it non-Guild, or weÔÇÖre not going to do the show,ÔÇÖÔÇàÔÇØ Fink says. (The show eventually went Guild in its second year, but only after several Comedy Central shows threatened to strike.) That attitude has permeated the industry, he says. ÔÇ£When I was making the transition from being a stand-up comedian to a comedy writer [in 1995], shows that employed comedy writers were all Writers Guild shows, so there was a minimum salary even for the most rookie writers. But there is a bit of a take-it-or-leave-it attitude now.ÔÇØ

At the heart of the issue is the larger fight thatÔÇÖs been raging in recent years about whether the Writers Guild has the heft to represent its members in an ┬¡industry upended by the proliferation of cable programming, reality shows, and the entrance of new players (Netflix, Amazon), new platforms (Hulu, Apple TV) and new formats (webisodes). Back in 2007, the WGA bet it all by ┬¡holding a strike that led 12,000 writers to walk off the job for three months, effectively shutting down the entire industry. While some issues were resolved during that strike and in the years after, others persist. Among them: the WGAÔÇÖs efforts to get basic-cable channels like Bravo and E! to agree to the terms negotiated by the industry.

Rather than wage a war with these cable networks, the WGA has employed a different tactic: tackling one show at a time. ÔÇ£They find writers who want to unionize on shows that are popular, and which also have producers who are sympathetic. Then these shows become models to move forward and gain a foothold into the network,ÔÇØ says Miranda Banks, author of the upcoming Scripted Labor. Two years ago, the WGA-West succeeded in unionizing Chelsea Lately and The Soup. Those negotiations, however, took more than six months to complete, and, according to the writers, only progressed after those showsÔÇÖ hosts, Chelsea Handler and Joel McHale, sent letters of support for the WGA to the network.

It isnÔÇÖt hard to understand why the networks resist. Shows like Fashion Police are among the least expensive to produce, since they have a smaller staff and lower production values. Once union contracts are added into the mix, the costs invariably rise. Not only do the networks have to provide salaries that can be five times as high as what theyÔÇÖre offering, they need to pay into a health and pension plan, not to mention paying residuals and new-media fees that also bump up the costs.

While Rivers hasnÔÇÖt publicly sided with the striking writing staff, the network claims she has been supportive all along. Earlier this year, she performed at a benefit to raise money for one writerÔÇÖs double hip-replacement surgery, and when E! announced that the Oscars special would run 90 minutes instead of an hour, Rivers asked the producers to give the writers more money. Rivers would not comment for this story, but a representative claims that the February meeting went poorly because the writers were airing grievances in the wrong forum. The representative also claims that Rivers sent a letter to E! president Suzanne Kolb in support of the writersÔÇÖ right to unionize. (Says Rice of the letter, ÔÇ£She wasnÔÇÖt forceful enough.ÔÇØ) In the meantime, many of the striking writers have gone on to find new work, and the WGA has banned any of its members from working on Fashion Police.

Within the next few weeks, Rivers will face a three-member WGA East panel that will review whether she violated union rules by performing showrunner duties after the strike began. The penalty could be anything from a fine to expulsion. Rivers issued a statement of her own: ÔÇ£This is such a bunch of bullshit. E! should hire Anthony Weiner to work with [the WGA]. HeÔÇÖd fit right in.ÔÇØ

*This article originally appeared in the August 19, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.