“Here it is,” Patti Astor shrieks. “Here’s my little gallery!” Astor is standing outside a tiny basement storefront at 225 East 11th Street in New York City’s East Village, where she and partner Bill Stelling opened the original FUN Gallery in 1981. That was the year after she starred in Eric Mitchell’s landmark low-budget flick Underground U.S.A. and a couple years before her turn as a reporter in Wild Style, Charlie Ahearn’s celebration of early B-boy culture that features the graffiti artists Lee Quinones and Lady Pink Fabara, as well as hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, Astor’s then-boyfriend and a future host of Yo! MTV Raps.

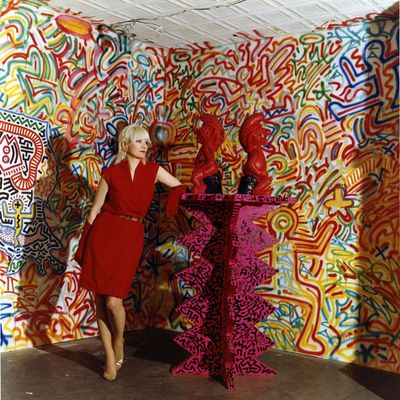

If you’ve never heard of Patti Astor, it may be because she’s one of those people who should take credit for things but doesn’t. Back in the day, she was more interested in making sure the young artists she championed — graffiti masters like Dondi, Zephyr, and Futura 2000, as well as Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and Jean-Michel Basquiat — were properly respected. She’s still at it some 30 years later.

“We were the first gallery to give one-man shows to graffiti artists,” says Astor, poking her head into her former gallery, where a guy is renovating the tiny space. “Our first hit of the big time was [Fab 5 Freddy’s] show. I remember sitting in the gallery, in that tiny room, and Bruno Bischofberger drives up in a limo like a city bus. He looked like Goldfinger and had a babe on each arm. I didn’t know who he was at the time, but [sculptor] Arch Connelly, who was kind of like our art guardian, later told me that Bischofberger was the second biggest collector in the world after Count Panza.” Astor, who sounds like Roseanne Barr, cackles at how ridiculous the names sound. “Anyway, Bischofberger dumps the babes and pulls out these index cards and starts asking me all these questions: Who is the most important person in graffiti? What do you think of Basquiat?” She snorts derisively. “I couldn’t believe it when I saw Tamra Davis’s documentary about Basquiat, which is really valuable for all the footage of him, but the rest is revisionist bullshit. Bruno and all these other people were like, ‘Yeah, we were really good friends.’ And I thought, You fucking pricks! You all treated him so poorly. Fred is the only one in the documentary who was a real friend of his. It really pissed me off.”

Diatribes like that could be another reason Astor isn’t better known; she’s not what you’d call political. Take, for example, her opinion about Julian Schnabel, who was an aspiring artist and fry cook when he first started hanging out at FUN. “Julian was really nice when he was still a cook,” says Astor. “But he got a real chip on his shoulder because he was a fry cook and not some world-famous fat slob artist. And then, of course, he fulfilled both of those goals. I loved how in his Basquiat he took 40 pounds off himself. That movie also makes me sick — that whole scene of him telling Jean-Michel what to do, like they were friends, which they weren’t.”

Don’t even get her started on Jay Z referencing Basquiat.

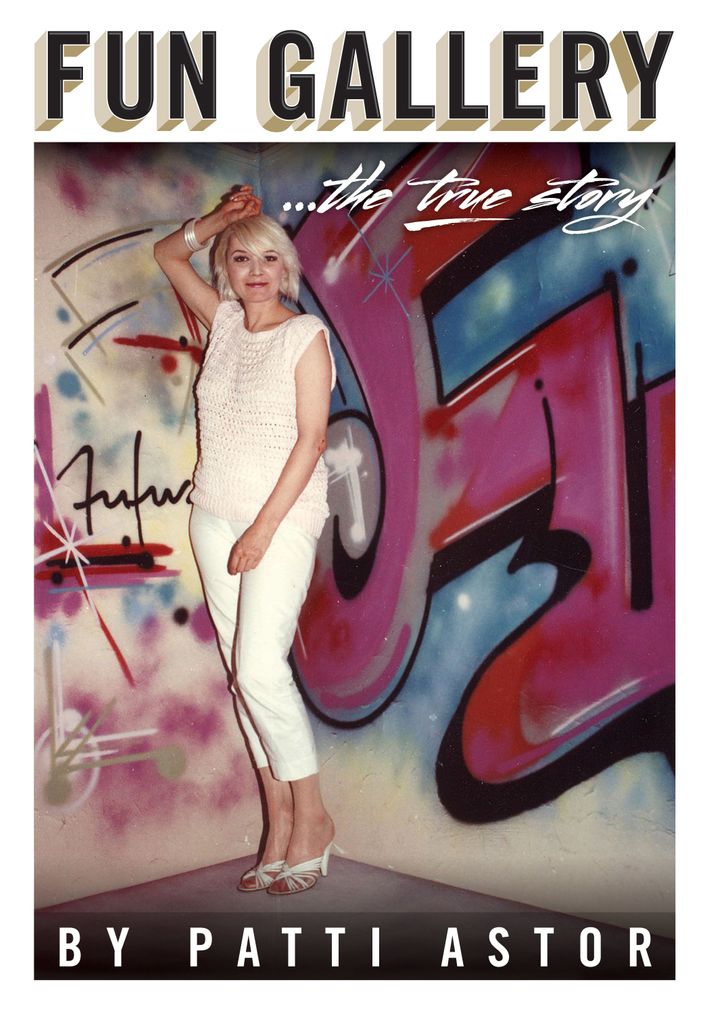

Astor has written and self-published a memoir, Fun Gallery … the True Story, a funny, no-bullshit chronicle of the East Village art scene in the 1980s, as well as her own rather remarkable and picaresque journey, from perfect suburban childhood to joining the SDS in the sixties to dealing pot in seventies San Francisco to tap dancing in Paris to underground movie stardom to doyenne of graffiti art. “One reason I got along so well with the graffiti guys was that they always had really good pot,” says Astor, who also drank a fair amount of Champagne. “They were all ambitious, as well they should have been. People are always saying I should promote the fact that I discovered them, but those guys would have been successful if I hadn’t been there.”

The first FUN Gallery was voted one of New York’s most important cultural spots by an art magazine. “There was a plaque, but somebody stole it,” says Astor. She tells the guy doing construction inside that this used to be her gallery. He feigns interest, and quickly gets back to hammering. “A lot of people ask me why I don’t open another FUN Gallery in L.A.,” says Astor, who moved out west when FUN closed its doors in 1985. “But I’m never gonna have Keith and Kenny and Jean-Michel walk into my life again. I seriously doubt it anyway. It’s probably one of the reasons I’m so broke, because I don’t keep doing the same thing over and over again — that’s how you make money. And now everything is about money. There’s no street culture anymore, or people doing things just to do them.”

Astor lives in Hermosa Beach now, in a trailer park populated with surfers. She occasionally guest curates at L.A. galleries, and slept on an assistant’s couch for eight months to work on the landmark 2011 graffiti show “Art in the Streets” at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. “I did it for the same reason that I wrote the book,” says Astor. “I feel I owe it to Dondi and A-One and Rammellzee and Keith and Jean-Michel, and the list goes on. I owe it to those guys because I made them a promise that I would always represent them in the way they wanted to be seen. Just because they’re not here anymore doesn’t mean I don’t still have the responsibility.”

We decide to look for FUN’s second location, on 10th Street, which was a bigger space. We walk east across 11th Street, the route Astor would take as she staggered home from the Mudd Club, decked out in head-to-toe vintage, at 5 a.m. Astor, along with Anya Phillips (girlfriend of punk legend James Chance) and the late Tina L’Hotsky (actress and Mudd Club queen), popularized the whole eighties vintage craze that Pat Field would eventually turn into big business with Sex and the City. Astor took it the furthest, accessorizing her mother’s old dresses with “gloves, hats, full on,” she says. “I did push it pretty far.” She was around the neighborhood for punk rock and I ask if she saw the Met’s show “PUNK: Chaos to Couture.” “That was a travesty,” she says. “There wasn’t any punk in that show — it was a blatant tradeoff for those designers. You know what was punk? Eric Mitchell running around St. Marks Place in green garbage bags and black tape.”

It must be depressing to see everything you loved because it was underground — punk, hip hop, graffiti, street culture — monetized and marketed. “That’s why I almost never come back to the East Village,” she says. “Gentrifying motherfuckers. I knew everything was going to shit when the St. Marks Cinema became a Gap.” (It’s now a vacant store on the corner of 8th Street and Second Avenue). We pass a gluten-free bakery — another thing you don’t want to get her started on — and eventually find the site of the second FUN at 254 East 10th Street, now an undistinguished apartment building. It’s all just too tame and quiet for Astor, who may be one of the few people who misses boom boxes, which is how she first heard hip-hop. Now she only sees the boxes fetishized on Facebook. “There’s two groups that I know of that are devoted to nothing but boom boxes,” she says. “They post photos of cassettes — blank cassettes! They message each other, “Ooh, that’s so fresh, brother! You have serial number blah, blah, blah.” Astor laughs. Do they play the boom boxes? “They would never touch them, are you kidding me?”

She’s devoted to a group of Brits called Official Aging Beat Boys Unite, who do a weekly radio show of old and new hip-hop; they revere Astor and send her mixtapes. “There’s a whole generation of fans who were 10 when Wild Style came out,” she says. “It’s their equivalent of me seeing Elvis Presley on Ed Sullivan when I was five. I told one of them about meeting D.J. Numark from Jurassic Five and how he told me he’d seen Wild Style 30 times. And this guy said to me, ‘Come on! I must have seen it 100 times.’” She laughs. “These guys are fanatics. They post photos of themselves in front of the milk crates that hold their records. You need to have ten crates to be taken seriously. I have this horrible feeling that some of them have 30 or 40 crates. You definitely don’t want to be the wives or girlfriends of these guys.”

We head over to the Astor Place Cube because she wants to show me where she first met Keith Haring. “I was coming this way,” she says, facing east, with the cube behind her. “He had a little camera and his google sunglasses. I didn’t know who he was yet, but he knew me. He asked if he could take my picture. And I said, ‘Of course.’” She re-creates the pose, smiling demurely, as she must have back then. The years melt away.

Read a lot more about Patti Astor and the 1980s art scene in her book, FUN Gallery …The True Story ($40).