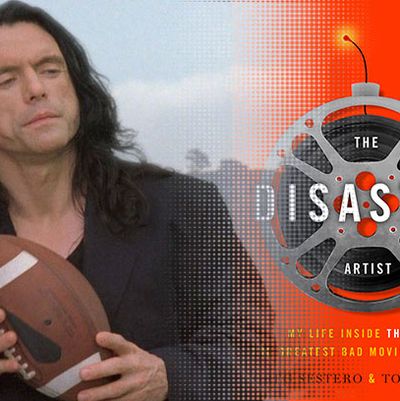

As anyone who has seen The Room can attest, the 2003 film from writer, producer, director, and actor Tommy Wiseau isn’t just awful, it’s hilariously awful. On Tuesday, Simon & Schuster will publish The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made, Greg Sestero’s first-hand account (co-authored with Tom Bissell) of the making of the film. In the following excerpt, Sestero describes the improbably difficult task of getting Wiseau to set on the first day of shooting.

On the first day of The Room’s production it was my job to make sure Tommy got up and to the set on time. This would remain my job for the entirety of filming, during which Tommy was routinely three to four hours late. In my defense, Tommy’s interior clock is more attuned to the circadian frequencies of a bat or possum than a man. He typically goes to bed around six or seven in the morning and gets up at three or four in the afternoon. Yet he was insisting on morning shoots for The Room.

After quitting my job at French Connection, I parked my Lumina in Tommy’s driveway. I walked through his front door, which was ajar, and called his name. No answer. There was a kettle of boiling water on his stove, whistling away. I took the nearly empty kettle off and went upstairs. Tommy’s bedroom door was closed but I heard him make a few grumbly noises, one of which sounded like “Five minutes.” I went back downstairs and sat on his couch, where I found a note from him to me that said: “You will receive majority of candy (95%) when completion of production. I’m not Santa Claus.”

“Candy” was Tommy’s unusually creepy slang for money. It was typical Tommy behavior to delay revealing an agreement’s fine print until after the handshake.

After twenty minutes, I went back upstairs and knocked on his door. “Five minutes,” Tommy said again.

I realized, sitting there on his couch, that there was a pretty significant loophole in Tommy’s payment plan: What if we never completed production?

Tommy briefly appeared on the staircase, looking disheveled. “We take your car, okay?”

“Okay,” I said. “But why?”

“Because these people talk if they see my car.” He started heading back to his room.

“We’re late,” I said. “When will you be ready to go?”

“Five minutes,” he said.

Soon I was lying down on the couch. Tommy’s plan was kind of ingenious when I thought about it. How better to incentivize my in- volvement in the film? How else to convince me to wait on his couch for an hour after he told me he’d only be five minutes?

What was Tommy doing? Primping, getting dressed, getting undressed, reprimping, doing pull-ups, getting dressed, primping again, falling asleep. At one point I marched up the stairs to inform Tommy that he couldn’t be two hours late on the first day of filming his own movie. But before I could give him this blast of tough-love truth, Tommy walked out of his bedroom wearing white surgical gloves stained to the wrist with black hair dye. Tommy had actually decided to redye his hair before heading over to the set. I went back downstairs and started watching Spy Game. Tommy had hundreds of DVDs scattered all over the floor, though I’m not sure he watched many of them. By the time Spy Game was over, Tommy was ready to go. We were four hours late now — and we hadn’t even stopped at 7-Eleven for Tommy’s customary five cans of Red Bull. I think this could be deemed an inauspicious beginning.

The Room was being filmed on the Highland Avenue lot of Birns & Sawyer, which over the last five decades had become a legendary provider of cameras and equipment to mainstream Hollywood film and television productions. Birns & Sawyer’s owner, Bill Meurer, had made the unusual decision to let Tommy use the company’s parking lot and small studio space because Tommy had made the breathtakingly expensive decision to purchase, rather than rent, all his equipment. This was a million-dollar investment that not even a large Hollywood studio would dare. Camera and filmmaking technology is always improving and anything regarded as cutting-edge will be obsolete within twelve months. Tommy’s purchases included two Panasonic HD cameras, a 35mm film camera, a dozen extremely expensive lenses, and a moving truck full of Arriflex lighting equipment. With one careless gesture Tommy threw a century of prevailing film-production wisdom into the wind.

Probably the most wasteful and pointless aspect of The Room’s production was Tommy’s decision to simultaneously shoot his movie with both a 35mm film camera and a high-definition (HD) camera. In 2002, an HD and 35mm film camera cost around $250,000 combined; the lenses ran from $20,000 to $40,000 apiece. And, of course, you had to hire an entirely different crew to operate this stuff. Tommy had a mount constructed that was able to accommodate both the 35mm camera and HD camera at the same time, meaning Tommy needed two different crews and two different lighting systems on set at all times. The film veterans on set had no idea why Tommy was doing this. Tommy was doing this because he wanted to be the first filmmaker to ever do so. He never stopped to ask himself why no one else had tried.

I navigated my loud, coughing Lumina through the parked trucks and construction equipment toward Tommy’s reserved spot, which had been ostentatiously blocked off with large orange cones. Guess who put them there?

The best description I ever heard of Tommy was that he looks like one of the anonymous, Uzi-lugging goons who appeared for two seconds in a Jean-Claude Van Damme film before getting kicked off a catwalk. That’s what Tommy looked like now, sans Uzi. This particular day, he was wearing tennis shoes, black slacks, a loose and billowy dark blue dress shirt, and sunglasses, his hair secured in a ponytail by his favorite purple scrunchie. As we walked from the car to the set, he was yelling in every direction: “Why are you standing around like Statue of Liberty? You, do your job! You, move those here! And you film operators, don’t touch anything for HD. Be delicate! We need to hurry! There is no time for waste!” Everyone stared back at him with expressions that said, Are you fucking kidding me? Tommy was ludicrously late for his own shoot and his first leadership step was to hassle the crew? It was not a hot day, but already I was sweating.

Copyright © 2013 by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell. From the forthcoming book The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell to be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.