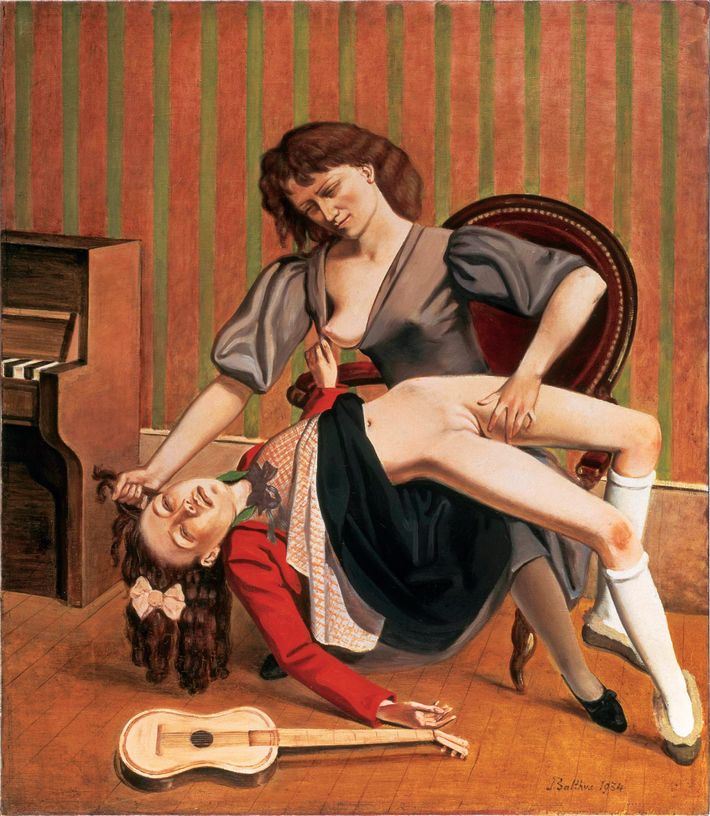

Henry Darger’s little girls, Gustave Courbet’s genital close-up, even Picasso’s explicit depiction of fellatio: You might think we had passed the point where a major painting by a first-tier artist is still taboo. Nonetheless, The Guitar Lesson, from 1934, by (the bogusly named) Count Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, is just such a forbidden work. At its 1934 debut in Paris, it was shown for fifteen days, covered, in the gallery’s back room. In 1977, it appeared for a month at Pierre Matisse’s 57th Street gallery. It has never been exhibited again, as if it were some metaphysical equivalent of the cursed videotape in The Ring that kills anyone who views it.

In his review of that 1977 show in New York Magazine, Thomas Hess lamented that it “can’t be illustrated in the pages of New York.” (Well, times change.) Alas, you also won’t see it in the scintillating “Balthus: Cats and Girls,” opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this week. The exhibition’s organizer, Sabine Rewald, is by far the greatest Balthus scholar ever, and her show’s theme and focus may justify its exclusion. So it remains frustratingly, heartbreakingly hidden from view.

Right after the 1977 exhibition, Pierre Matisse offered to donate this work to the Museum of Modern Art, and it was even delivered to MoMA. There it sat, stored, until 1982, when Blanchette Rockefeller, the museum’s president and a huge donor and fund-raiser, saw it and demanded that MoMA refuse the gift. It went back to Matisse’s gallery, where it was sold (to Mike Nichols), then resold again and again, ending up with the Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos. He, according to Balthus’s biographer, kept it in “an elaborately paneled bedroom, furnished like rooms at Versailles … [next to] a king-size container of Preparation H.” He died in 1996, and the painting remains with his heirs.

Balthus is a difficult artist. Obnoxious. Cheesy. Stiff. Yet by fusing conservative technique with surreal setups and subject matter drawn from the deep reservoirs of sadomasochistic imagery and erotica, his painting is a world apart. I don’t love Balthus’s work, but I grant that all parts of the best examples are charged with something wild, almost half-human, some sleeping need, rage, frustration, and restraint. What makes the banishment of The Guitar Lesson so bitter isn’t only that MoMA came this close to owning a second take on the blatant sexuality of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It’s that, in this one work, Balthus broke through his overweening coyness, predictability, and button-pushing theatricality, depicting a truly mysterious, open-ended picture of our strange, strange loves. Rewald is perhaps the only Balthus scholar who could have let us see this forbidden painting in the best light. I’m sorry she didn’t bend the rules of her show and reveal this exquisite deviation.

*This article originally appeared in the September 30, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.