NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts will honor Tisch alumnus and Academy Award–winning film director, screenwriter, and producer Oliver Stone for Outstanding Achievement in the Cinematic Arts at its annual benefit gala, being held tonight at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in Los Angeles. Vulture’s Matt Zoller Seitz talked to Stone last week about his experiences at NYU after Vietnam, and what he learned from his film teacher Martin Scorsese.

Did you go into NYU shortly after you got back from Vietnam?

It was about six months later. I went to the School of Continuing Education to take courses in the summer. Put it this way: It was a rocky time period when I got back. Six months of uncertainty and alienation. A lot of confusion.

Where were you living at that time?

I was living in various apartments in the Village. East Village. Lower East Village. On the edge of Little Italy, etc. Various places.

Did you know a lot of veterans at the time?

Nobody. Nobody that I knew except one person, but he had not been in combat. I’d known him before the war. He came back, and he was in another world completely.

Did you go to NYU specifically to study film, or did you go for some other reason?

It was a little bit more vague than that. A friend of mine had said that he had taken up film as a career, and other people said there was this film [studies course] in school, which may not sound strange to you, but it was a pretty strange idea back then — to go to a class that was dry and academic, and to actually be able to watch films in the middle of the day and write about them. It was pretty wild. Pretty wild idea. It was in the air.

I realized that I did not have a college education, and also the G.I. Bill in those days was covering about 80 percent of the tuition, which is not that high, but still, that was 80 percent.

You had started out at Yale, and you didn’t finish?

No, I didn’t finish. I left Yale twice to go to Vietnam. The first time was as a teacher and as a merchant marine sailor [that] I went there. And then the second time I left there and I ended up volunteering, and then when I got out of the service in November ‘68, I drifted back to Yale and had a hard time, as I said. … In the fall I actually enrolled at New York University undergraduate film and in September ‘69 — I graduated in June ‘71, so two years — and I did summer school, also, both years to speed it up.

I know that you took photos when you were in Vietnam, and that you were a writer from a very young age, but do you remember if there was any particular point at which you said, “Not only do I like movies, but I might like to make them as well”?

It was a little slower than that. I had always been interested in writing since I was a child. My father had encouraged me, paid me money to write. And I got a weekly allowance. So, I wrote short stories and plays. I wrote my book, a book you may be familiar with it, A Child’s Night Dream. It’s a very important part of my life. Something that I submitted and finally got published 30 years later.

So when I went to film school, yes, I had always liked film, but I had never thought that it was possible to get a life in it, because everyone there was kind of a blessed person. I didn’t have any connections — family connections, and so forth. So I didn’t really think that was realistic, and my father was always very realistic. I didn’t know what to do.

The classes were interesting enough, and it seemed like a novel idea, so I went, and in that freshman year I was very lucky because the teachers were great there. Among them was Martin Scorsese. Marty was there, and we didn’t know who he was. He was just a wild-haired, fast-talking New Yorker with a passion for film.

He had already released his first feature by that point.

Who’s That Knocking at My Door.

Do you remember the first time you met Scorsese? Can tell me what impression he made on you? How did he strike you?

A nutcase. A New York nutcase.

I knew a lot of cranky New Yorkers. People who talk fast like Joe Pesci in the movies, the kinda wiseguys. You could barely see Marty’s eyes. He had hair down over his forehead and ears. And definitely funny.

He always looked like he’d not had enough sleep because he’d probably been up the night before looking at all the films on TV. That’s the only way we could see them back then unless you went to a museum. Understand, there was no such thing as video. He would stay up pretty late to watch these old classics on the local channels. And as he was up, I don’t think he slept too much, he would have an early class. I remember him talking fast. I can’t say I understood everything at all. I do remember his enthusiasm and his energy for the subject matter and he was definitely a young protégé. He was the protégé of Haig Manoogian, who was the presiding chief.

What course did Martin Scorsese teach?

Marty was our instructor in Sight and Sound.

What was Sight and Sound?

That was an introductory production class. They taught us the art of filmmaking, and we looked at each other’s films. We had a collective where we’d make three or four short films of 60 seconds up to three or four minutes each over the semester. We all took turns directing, writing, editing, acting.

And then the next semester I guess we moved up to a higher grade. We showed films. We talked. All the theoretical classes, the screenwriting classes, the ones that I took, not everyone was forced to take. Basic Sight and Sound was a chance to make these very low-rent films, black-and-white 16 millimeter, with the NYU equipment and footage. Not much footage — you had to be economical.

I can say that honestly, most of us didn’t know what we were doing, for the first couple of films were very clumsy. But we’d have critiques. Like a Chinese communist collective, we’d come together and watch these films. There’d be pretty harsh criticism. But it was a part of that growing process. You had to sell your idea to the class. And have much critique.

And at that time, I was very confused by the war and I didn’t talk about it at all to anyone. I really was into myself. Quiet. And most of the ideas [in the other students’ movies] were pretty radical to me, and progressively left. Most of them were New York people or — how do you say? — Eastern people, and they were definitely into documentaries about Mao, tunnel workers, labor unions. There was huge interest in what you’d call the left documentary cinema at NYU. George Stoney [Editor’s note: creator of some 50 nonfiction films, including the midwifing documentary All My Babies] was one of the teachers. … There was a left documentary tradition that had gone back at NYU, back to the forties, I think, maybe sooner.

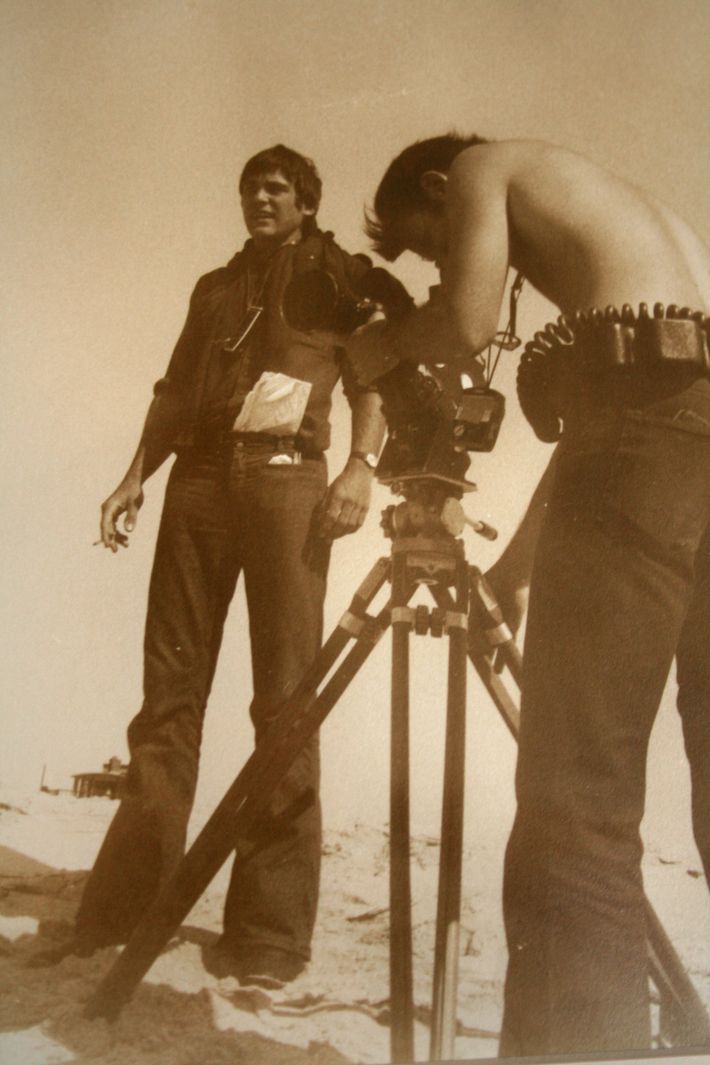

As the semester went on, he was so into film that I don’t think he personalized the students that much. And I remember sometime along the way, I think it was that first year in the spring maybe, I had done a film with a silent soundtrack — there was no dialogue except for voice-over — called Last Year in Viet Nam. I put myself in as an actor and alter ego. It was the simple story of a young man who is a mystery. He has a limp. And basically, through the course of this twelve-minute movie, takes all his possessions from Vietnam and dumps them in the East River from the Staten Island ferry. But it’s nicely done.

And when he saw it, Marty gave me — he said to the class, “Here’s a filmmaker.”

And he’d been so critical of other films through the semester that it did make an impact on me.

When you showed your film about your Vietnam experience to the class, did everyone in the class know by that point that you were a veteran, or were some of them surprised?

I don’t know. Frankly, Matt, I didn’t talk to all of them. I was never asked about it. And if they knew, then certainly I would have been on the wrong side of the fence.

Were you politically conservative?

Yes, yes, I was. I was raised that way. I was Republican. My father was conservative, and very much so.

When you’re describing the politics of the students and the department, you described them as being radical left or kind of “New York left.”

To me, they were. Everybody had to make documentaries about a tunnel worker or about whatever movement was in: black power, revolutionary party stuff. In fact, the school in 1970 went to the left completely, and revolted as part of the Cambodian bombing and the Kent State killings. The students took over the school. No teachers were allowed in, and they trashed the place. I joined the team.

I was a cinematographer on a documentary that Scorsese ultimately ended up editing and directing. It was called Street Scenes 1970. It was about those protests in New York [and Washington, D.C.], which were pretty big. They were on Wall Street, they smashed our cameras, one of our cameras — they didn’t have much left after that. I think it was May of ‘71. They didn’t have much left. The whole thing was taking over.

Was it in May of 1970? Sometimes I get lost on the timeline. You can always check that. Whenever the Cambodian thing — was it May?

It was in May of 1970, yeah.

And I must have done another year after that. I did cover the protests, shot them, and some of my footage is in that film, but I was not part of it. I was not protesting against the war. Definitely not. And I was mixed up.

Were you against the protests?

I can’t tell you I was against them — but to some degree, yeah. I think there was conflict, because we talked so easily about revolution and shit like that, and it was hard for me to buy that, unless you were willing to get a gun and go somewhere on a rooftop and do something about it. Because I was coming from a more practical experience. So, for me, it was a lot of talk: bullshit.

And when the big thing happened, it was a mess. They didn’t know how to organize themselves.

Actually, the black revolutionaries were the ones who took over the whole thing. I remember they were the most radical. And they were like, “What do you white boys know?” All that shit. So it was a little bit racist, a lot of racism going on there. And I think the negative kind. I’m not saying Black Panthers were bad, because they did a lot of good stuff, but a lot of negative Black Panther shit went down [during the 1970 protest]. So, it was ugly.

[The place] was like a fucking pigsty after a few weeks. “Liberated bathrooms” and all that shit. It was just a mess. They couldn’t clean up their own stuff! It wasn’t like the army. where you have some self-discipline. [Laughs.] You understand what I’m saying? Nobody’s taking care!

So, I didn’t like that shit. So I was into getting things done, whether it’s getting into film school, getting a career, or something.

You were a soldier.

I was! But I didn’t relate to a lot of that mentality.

Anyway, I graduated into being a cab driver and so forth.

Can you put on your documentarian’s hat for a second and describe to me what NYU felt like in that period? What were the students like? What were the buildings like? What were the sounds and smells like?

For the most part, the experience was pretty grim and grimy. Some of the students had money. Most of them were living hand to mouth.

Like, a bunch of students living in one apartment?

Yeah, there was a lot of that. Lot of that.

I had a broken window on Houston and Mott, I think — a broken window apartment, and snow drifted in.

And this woman, I started living more and more with her, at her place. And I came back from the dead with her.

You came back from the dead. That’s quite a statement.

So to speak. Metaphoric. I couldn’t integrate into society. I had to integrate into society. It was easier if you had been over there, and then you came back to a place where people were supportive. But most people weren’t like that. Most of them, they’d think about it for two seconds, and then it was like, “Oh man, what a dummy,” or, if not that, then: “That poor guy, he went over there. What a waste of time.”

It was the thing: You dropped out, and nothing had happened except you lost your mind for a while. It was a strange phenomenon to be pitied or to be ignored, but I’ve gotten used to it in my lifetime. [Laughs.]

I don’t think I had a great time. But I met a woman. [Author’s note: Najwa Sarkis, to whom Stone was married from 1971–77.] I liked her; I married her. We ended up living together for seven years. So, I was lucky with her ‘cause she really put my life back together, gave me a sense of integrity. Warmth.

Societal relations, that’s very important. I was alienated deeply from my parents at that time, and from American society. I don’t know why, I just felt terrible.

The scenes in Heaven and Earth that show Tommy Lee Jones’s veteran character failing to reintegrate with society after the war — are those scenes in any way drawing on this part of your life? The postwar period?

No, no! Although I think I could identify with someone like Tommy Lee Jones coming back, and also [the film’s heroine, a Vietnamese immigrant played by Hiep Thi Le] coming to a society she couldn’t recognize.

[Pause.]

Yeah, you’re right.

I took a lot of LSD. I didn’t go into that with you earlier. Obviously, in that period, LSD and all kinds of [drugs were popular] in New York. I was smoking since Vietnam. I was very reckless in some ways.

When you look back on that period, what’s the single most important experience you had during those years at NYU? Can you think of anything?

That’s not fair! Life? All that pussy?

[Laughter.]

Maybe it was just going to film school. Certainly it focused me. I started to become more and more interested. The more I knew, the more interested I became. That’s a pretty conventional story, but it’s the truth.

Try to imagine you are able to travel back in time and see yourself as a young man. Can you describe this kid? What did he look like? How did he carry himself? I’m just trying to picture you.

You see it in the movie. If you look at Last Year in Viet Nam on YouTube, you’ll see it. You can see it in that movie. You can see it in the look. It’s very dark, wearing black a lot, boots, very, very — I looked like a young actor. Maybe like a distrusting Russian! A little bit of a Russian thing. Distrusting. I could have been … I used to wear a peacoat jacket. It was more like I was a Travis Bickle type. Outsider.

I was also older. I was two or three years older [than the other students]. So I would say to you that I was dark and broody, and that I was not in general agreement with a lot of the dialogue, which I thought was pitter-patter or sophomoric. I didn’t wanna go back to college, ‘cause I had been at Yale. I didn’t wanna go back to a fuckin’ college! I didn’t believe in that group. I didn’t believe in that goal. I didn’t want be … My dad wanted me to be a socioeconomic product of a niche institution, like he was. Join Wall Street or the banking community or business. Business was the way to make money. I was resisting that, and college was part of that.

A lot of the NYU stuff was much more mundane. A lot of boy-girl stuff. And I wasn’t into any of those girls. I was into older women.

You were?

The woman I married was six years older than me. It was just that [older women] were more mature, more interesting. I wasn’t into the college life. I wasn’t into sophomore-junior shit. Yes. You got a picture now?

I do.

I moved out of Houston Street. I had a horrible place on 9th Street. God, it was the pits! Between Avenue D and C, I think it was. I painted it red. I was insane. I painted it all red: ceilings, everything. Bright red. And I also got ripped off there about three or four times, by people coming in through the window and shit. It was insane. That was when the East Village was pretty nasty.

Then I moved uptown to my future wife’s apartment and I stayed there.