The woman seems like she must be beautiful, although you can’t see her face. In the photograph, she stands with her back turned, gazing into the woods on a sunny day in late fall or early winter, her dark-blonde hair brushing her shoulders, almost tangibly present but at the same time unreachable. She’s real, but only in her world, not yours.

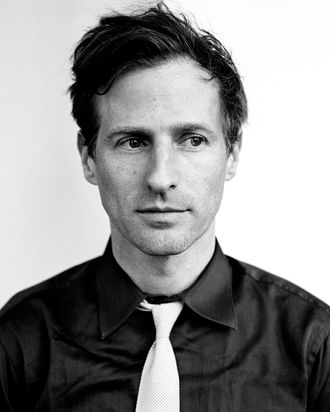

The print, by the artist Todd Hido, hangs on a wall near a giant rectangular dining-and-conference table in the loft where Spike Jonze lives and works when he’s in New York. Several years ago, Jonze saw it in a gallery and felt stirred by what he calls “the beautiful mysteriousness of it. And also, you know, the memory of it.”

Around a corner from where we’re standing, a bedroom glows behind a wall of curtained glass, but the flow of Jonze’s sunsplashed Lower East Side living space allows him to pad barefoot from where he writes to where he plays music to where he has meetings to where he eats to where he hangs out. Jonze grew up on the East Coast but has recently spent much of his time in Los Angeles, and the loft feels capacious enough to accommodate his many selves—one can imagine the skateboard brat of the eighties heel-flipping across the floor while the subversive-music-video prodigy of the nineties blasts the Beastie Boys and the still precocious but mature film artist of the last ten years shuts out the noise and works alone at his desk. His home is large enough to accommodate a crowd, but it’s designed for a party of one. Specifically, for a grown-up who wants room to think.

“It feels like a memory,” he says, raising his fingers toward the photograph. “The mood of a day without the specifics. A memory of this girl, in this beautiful, funny forest.”

When Jonze started to write his newest film, he made a small editorial addition to the image—a ragged piece of a yellow Post-it note that he stuck on the glass over the photograph. Then he took it off, replaced it with another, and then another. On the one that he finally decided felt right, he had written three lowercase letters in black marker: her.

“Huh, that’s still there!” he says, pleasantly surprised.

The movie that grew from that gesture will have its world premiere as the closing-night attraction of the New York Film Festival on October 12 and will open in New York on December 18. Her is not about the woman in the photo so much as it is about the man longing, perhaps hopelessly, to connect with that woman. It may be the most personal film yet from a director who has long juggled so many personae that his actual identity remains deliberately elusive, even after twenty years in the spotlight. The film, a wistful adult romantic drama set in a near-future L.A., is the first Jonze has written on his own as well as directed. Like his other work, it is searching, disarmingly sincere, and melancholy in surprising places. Her springs from a notion that could be played as rimshot contemporary satire: A sensitive, lonely guy (Joaquin Phoenix) coming off a rough divorce falls head over heels for a woman who’s literally custom-made for him—the artificially sentient female voice of his new computer operating system. But just as he did in Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, Jonze uses the gimmick to unlock a door to unsmirky human feeling. The result is not just a cautionary meditation on romance and technology but a subtle exploration of the weirdness, delusiveness, and one-sidedness of love. For all his imaginative conceits, Jonze is, in his way, a realist; he’s less interested in playing with the technologically extraordinary than he is in demonstrating the ways in which it can burrow into our most private selves.

“I always wanted it to be a relationship movie,” he says, “and that was at odds with it being high-concept-y.”

“Let’s go again! Right away!” It’s the morning of June 21, 2012, and Jonze is on Stage 6 at L.A. Center Studios, a lot in downtown Los Angeles the best-known tenants of which are currently Mad Men and The Voice. He’s about to shoot the sixth take of scene 45 of Her, in which his protagonist, Theodore Twombly, engages in some languid, quietly flirtatious bonding with his operating system while riding an elevated train.

On movie sets, many directors spend their time hunched over a bank of monitors in the electronic enclave known as “video village,” often at a considerable distance from what’s being shot. But Jonze is disinclined to root himself anywhere but where the action is; as the next take starts, he can be found about four feet from his leading man’s face and seven inches from the back of his cinematographer’s head. “It’s just the way I like to work,” he says. “I’d rather be close.”

In part, that’s because Jonze actually enjoys sweating the small stuff—the microtwitch of a reaction, the movement of light across Theodore’s face, even the contours of a three-inch prop. Onscreen, the OS, who names herself “Samantha,” exists as a small portable gadget, the look of which was inspired by a vintage Deco cigarette lighter that Jonze and production designer K. K. Barrett found in an L.A. antiques store.

For weeks before filming started, they and the rest of Jonze’s team, many of whom have worked with him for years, holed up in a suite of rooms lent to them by David Fincher (“He always gives us space before we have offices,” says Jonze). Every day, he and Barrett worked on fine-tuning the design of a future that they imagined would be filled with soft curves, handsome fabrics, and appealing lighting and textures—an idea Jonze says he first got, improbably, from the interior of a Jamba Juice, and then refined in talks with the partners of the architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the designers behind the warm and inviting reinventions of Lincoln Center and the High Line. “K.K. looked at a lot of futurism on YouTube,” he says, “but glass with screens in it, phones that looked like thin plastic cards, and nanotechnology just didn’t seem like our movie, aesthetically.” Instead, Jonze wanted to set Theodore’s solitude in a reassuringly comfortable milieu in which, says Barrett, “everything is bespoke, really nice, tactile, beautiful.” That includes the blond-wood, white train car built on massive springs that was, just an hour earlier, still being finished with hammers and drills, before Phoenix and a group of extras stepped into it and took their seats. “Everybody talk to your devices,” Jonze’s assistant director tells the passengers. “Just have whatever ordinary, mundane conversations you’d be having on the equivalent of today’s cell phone.”

Across the stage, Jonze is up, moving, always on his feet, the squeaky skid of his scuffed white sneakers echoing at a pitch high above the crew chatter and the metallic rumble of equipment that’s being rolled through the hangarlike space. “I’m surprised he hasn’t busted out the skateboard yet,” says producer and longtime colleague Vincent Landay. “He usually does. He was skateboarding around the set when he directed the Kanye video ‘Otis.’ ”

Jonze has directed four movies in fifteen years, a pace just deliberate enough so that every time he reappears, it’s something of a surprise. It’s not that he gives himself a lot of downtime—between movies, Spike the entrepreneur, Spike the music-video wunderkind turned eminence, Spike the skateboard punk, and Spike the daredevil all need room to play. This is the résumé of someone who, in Landay’s words, “likes to do stuff and make things”: innovative videos, short films, and successful ventures ranging from a skateboard business to an executive position with Vice Media, an upstart company whose underground-to-cult-to-mass trajectory neatly matches his own career arc. Even with a movie opening, he needs projects—he’ll serve as creative director for the first YouTube Music Awards in New York on November 3. He also remains committed to what he calls, only half-kiddingly, a “night job” as one of the creative overseers of the Jackass franchise; his latest collaboration with Johnny Knoxville, Jackass Presents Bad Grandpa, which he calls “a semi-scripted hidden-camera prank film with a narrative,” opens October 25. Jonze occupies a unique niche among American filmmakers—he’s a first-rank auteur who’s also such an idiosyncratic shape-shifter that he never seems entirely ready to join any club that would gladly have him as a member. Try to pin him down, and he’ll probably turn the pin into an art project. As he begins his third decade as a restless genre-hopper in the public eye, he remains one of the rare film artists who is equally respected in and out of the mainstream. He’s never been tagged a sellout, and—amazingly, given the accelerated pace of public taste and Internet mood swings—he has never not been cool.

As a director, Jonze has chosen to work slowly, privately, and without an eye on the calendar. He’s not a serial committer who attaches himself to five or six projects for every one he directs; he stands far outside the studio–agency–development deal food chain. At this point, he acknowledges, he’s pretty sure that people in the industry “don’t really imagine that I’m just going to read a script and want to make it.”

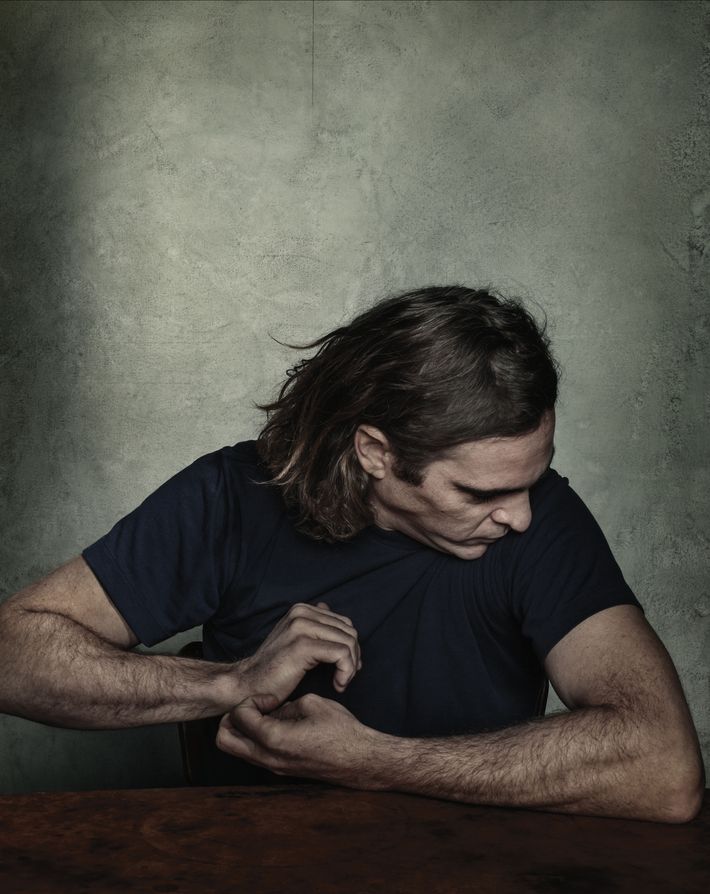

When Jonze was writing Her, he thought of the main character as being in his fifties, but he came to realize that there were advantages in making Theodore a younger man whose romantic misfortunes had knocked him down but perhaps not out. As soon as he finished the screenplay in 2011, he brought it to Joaquin Phoenix, then 37, whom he had met a decade earlier, when Phoenix read for Adaptation. The actor had spent the earlier meeting saying, “ ‘I fuckin’ can’t do this, I’m wrong, you don’t wanna cast me,’ ” Jonze tells me. “I loved him.” When Phoenix read Her, “I was astonished,” recalls the actor, who was then prepping for The Master. “I find it hard to focus on anything else when I’m working, so over the next year there were big gaps when I didn’t talk to him at all,” says Phoenix. “But when I was free, we’d talk and he’d make changes.”

Phoenix is, in some ways, an ideal doppelgänger for Jonze (or, at least, Jonze on a very dark day): He has also dabbled in pranking the media—the beard, the shades, the quitting-acting-to-pursue-a-hip-hop-career moment—and also alternates periods of retreat with surprise returns. Late-night comedians may use him as an occasional dartboard, but among his generation of actors, he is eccentric royalty, revered as someone who will wrench a performance of complete integrity out of himself no matter what it costs emotionally. Jonze describes him as “all instinct” and says that, as they went through the script together, “when something felt weird, when Joaquin was uncomfortable with something, I knew it meant there was some place I had cheated or hadn’t thought through or hadn’t gone deep enough. His flinch is always worth listening to.”

By the time production started, the two men had worked out a relaxed, shorthand conversational style. After a take, Jonze clambers onto the train set, perches next to Phoenix, and whispers in his ear. “I’m always amazed when any actor can decipher my direction,” he says. “I think, God, I can’t believe Joaquin just understood what I meant when I barely said anything.”

Phoenix nods, smiles, and makes a small adjustment for the next take, still closed off in Theodore’s lovestruck, half-dream state. Each preamble to the scene differs slightly from the last: At one point, Samantha invents a tune and asks if Theodore would like to hear it; she prepares for another take by humming him “I Wan’na Be Like You” from Disney’s Jungle Book, a song that, in this context, can be heard as her plaintive OS-to-human lament. While Phoenix listens to her, Jonze seems to engineer, without overtly requesting it, a kind of private space for him; everyone backs off a bit. “It’s very easy for film sets to feel scattered,” says Phoenix. “The most difficult thing for me on a movie is to focus my energy while many different things are coming together. It didn’t feel typical on this film. Everybody’s focus was in trying to make it feel intimate, and that’s an amazing feeling to have on a set.” I thank him for letting me visit, and he chuckles, shaking his head and nodding toward Jonze: “Thank him, man, because if it was up to me nobody would be anywhere near here!”

Jonze and his cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) readjust the green-screen projection outside the train window—Jonze is concerned that it looks like the railway is passing too close to the high-rises on the horizon; he doesn’t want his version of L.A. to look so congested. I ask Phoenix if he thinks Her is specifically a Los Angeles story, since it’s about people who enjoy the luxury of large private spaces and suffer the affliction of disconnection from others in a way that feels more West Coast than New York. Phoenix lived in Tribeca for a stretch in the late nineties, but after several years, he says, tucking a cigarette behind his ear, “I came back to L.A., and I got soft. You have a kind of space here where you’re not confronted by humanity the way you are in New York. Although when I was younger, I loved that confrontation. You’d walk out the door and there everyone is. That was exciting.” He asks if we’ve met before. No, I say, I have one of those faces, brown-haired Jewish-looking guy with glasses.

“But isn’t that what I look like?” he says, smiling and walking back onto the train.

In the movie, the flesh-and-blood women in Theodore’s life are portrayed by Amy Adams and Rooney Mara. But much of Her rests on the believability of Samantha, the incorporeal title character. When I visit the set in Los Angeles, she is being played by the British actress Samantha Morton, a two-time Oscar nominee and a Jonze alumna (she appeared in Synecdoche, New York, which he produced). In every one of Jonze’s movies, he has confronted himself with some sort of technical challenge—multiple Malkoviches, twin Nicolas Cages—and this time, he’s scripted himself a good one: an invisible co-lead whose presence will be critical to making Theodore’s amour fou plausible. Rather than prerecord the dialogue, he has decided to have Morton on set, performing her voice-only role with Phoenix in real time whenever possible. “I always knew they would have to be together, from the time we were writing it,” he says.

For her part, Morton has taken the assignment to play a heard-but-not-seen character seriously. She has spent much of her time hidden away in a four-by-four carpeted soundproof booth made of black painted plywood and soft, noise-muffling fabric. I find it tucked out of sight behind a giant screen and peek in. It’s a less than inviting place to spend more than two minutes. The only furnishings are a seat cushion, Kleenex, Chapstick, a makeup case, and a microphone with a spit guard. Jonze sticks his head in the box. “Sam had plants in here before,” he says. “They died.”

Morton has temporarily escaped the booth to make a rare appearance in the middle of the action. She drifts across the set swathed in a black, shroudlike, floor-length dress; she looks like she would hide her face if she could. “For the first weeks, she didn’t even want to come out of the box,” says Jonze. “She only knew the sound people. But now she’s started to emerge. And she’s always in our ears. She told me it’s the strangest environment she’s ever acted in.”

“My box was perfect today,” Morton reassures a set carpenter. “It’s the right size. I can stretch.” Atop a wooden table, cross-legged and meditative, she disappears into the background, and the busy crew barely registers her presence. Jonze strolls over and sits beside her, strumming a guitar. But she retreats before Phoenix steps onto the set; with Jonze’s strong encouragement, the two have tacitly agreed to remain in character by staying out of each other’s sight as much as possible.

On the soundstage, the mood is not tense but dense—concentrated, packed, and tightly timed. After production is finished, Jonze will give himself room to breathe—“For him,” Landay says, “a fairly aggressive schedule, if everything goes smoothly, would be to finish by the beginning of next summer.” But right now, the pressure is on. In three days, Jonze, Phoenix, and a very lean crew will fly to Shanghai for two weeks of shooting in which the new skyscrapers and raised walkways of the Pudong business district will double for downtown L.A. circa the day after tomorrow. Jonze had originally hoped to shoot Her entirely in China, making full use of modern Shanghai’s architecture and design aesthetic. But, although Warner Bros. will distribute Her, it is actually Jonze’s first film in more than a decade to be made without studio money, which necessitates some compromises. When the deep-pocketed 27-year-old maverick producer Megan Ellison, who produced Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master and Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty, agreed to finance the movie, Jonze decided to save money by doing most of the shooting in L.A.

The working days there are long. Lunch for the senior production team doesn’t start until 4 p.m., and when it does, it becomes clear that not for nothing is Jonze dressed in a tailored light-gray suit, a dress shirt with subtle pastel stripes, and a pale-yellow tie (an on-set look it’s hard to imagine anyone other than Wes Anderson pulling off). During the 30-minute meal, he’s as bombarded as the CEO of a tech start-up. Van Hoytema wants him to know that they’re going to need to use colored gels to achieve the effect he wants during the China shoot, and to air his distress that their window to film during the “magic hour” (around sunrise or sunset) is limited. Barrett needs to discuss the look of a giant LED monitor in one scene. And Jonze’s first assistant director crisply announces that “something has gone wrong with the casting process in China. They’re having trouble finding 100 extras with the right racial and age balance.”

Jonze is still one problem behind. “There was a location in Shanghai that had a monitor that spilled light onto a dance floor—that’s what I’m looking for with the monitor,” he tells Barrett. Someone slides a sheaf of photos across the table.

“These are the extras? We can’t have this many with short buzzed hair,” Jonze says pleasantly, handing the pictures back.

“Well, we could always use Ukrainians,” the second assistant director says in a tone that suggests this would open up a Pandora’s box of miseries.

“Two points about extras … ,” someone says, drawing a deep breath.

“Time,” somebody else says warningly.

“All right,” says Jonze, standing up. “Let’s go back to work.”

Jonze first emerged as a movie director as part of the “class of ’99,” making his debut in what turned out to be an epochal year that also saw breakthroughs for the Wachowskis, Kimberly Peirce, David O. Russell, Brad Bird, and Tom Tykwer, not to mention Jonze’s then-bride Sofia Coppola (the two married in 1999 and divorced in 2003). His contribution to the new-generation vibe of that moment was particularly auspicious: After winning good reviews for his first major acting role, as a hayseed soldier in Russell’s acclaimed Three Kings, he arrived months later as a director with Being John Malkovich, a surreal dark comedy about a sad-sack starving artist (John Cusack) who discovers a portal that allows him—or anyone else—to jump into the consciousness of the title character.

Jonze had won respect as a music-video director for Weezer, Daft Punk, and the Beastie Boys at a time when that was still primarily a dismissive term; his videos often felt like performance-art installations in which viewers were confronted with a technical innovation (the Pharcyde’s “Drop” is a long take that you gradually realize is being played backward), a haunting image (a man running down the street on fire in California’s “Wax”), or a put-on without a trace of snideness (the amateur public dance performance in Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You,” with Jonze co-starring as choreographer “Richard Koufey”).* But the soulfulness and assurance with which he handled screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s genre-busting script still came as a huge surprise. Jonze won the New York Film Critics Award for Best First Film and, at 30, an Oscar nomination for Best Director, the first time the Academy had ever recognized someone so strongly identified with the disdained realm of MTV. He says it was only around then that he started watching movies seriously: “I wasn’t a film kid,” he says, citing Fargo and Hal Ashby especially for showing him that movies could have many tones at once. “I think I probably suffered from what a lot of young people suffered from—‘Oh, that’s going to be old, that’s going to be old-fashioned.’ I’ve definitely thought, Oh, that’s a classic movie and then seen it and thought, Oh, no, no, that’s a great movie!” Malkovich was a high-end indie (it was made for $13 million), but now, the major studios were eager to get their hands on him. When he and Kaufman reteamed in 2002 for Adaptation, the result was every bit as acclaimed as Malkovich had been, and this time, Sony was writing the checks.

The critical success of his first two pictures won him the chance to work on a larger scale, but on his next movie, an adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are for Warner Bros., released in 2009, that Jonze co-wrote with the novelist Dave Eggers, “nothing was easy.” With a $100 million budget came the constraints of working for a studio that wanted something “indie” enough to please critics while still functioning as a family-friendly brand name. Given its prep time, its technical complexities (dubbing, puppetwork, CGI), and a protracted postproduction during which he and the studio fought over the film’s tone, “it was really like making six movies,” he recalls. Ultimately, Warner Bros. supported Jonze—Wild Things was an uncompromised, independent-feeling film with no blockbuster gloss, and it won the ardent admiration of many critics. But its exactly-break-even $100 million worldwide gross was disappointing, and it arrived at a post-crash moment when many studios were retreating from their flirtations with indie sensibilities.

Jonze, who had never before had his vision challenged by a studio’s economic imperatives, felt so wrung out that he took a year off before starting to write again. “I just wanted short, fun, interesting challenges,” he says. “If a movie is like a painting, I wanted to do sketches. When I used to make music videos all the time, that’s what they were like. ‘Here’s an artist I love, here’s a song I love, here’s an idea, let’s go make it.’ But this time I wanted to do things that originated from an idea I had as opposed to a song.” He and Kanye West collaborated on a short movie called We Were Once a Fairytale, and he co-directed a stop-motion-animation short called Mourir Auprès de Toi (To Die by Your Side), using characters made of felt. Then he accepted a commission from Absolut Vodka to direct another short, an idea that grew into I’m Here, a romantic seriocomedy about young love and sacrifice in contemporary Los Angeles—except with robots. The 31-minute film, which stars Andrew Garfield, feels in many ways like a warm-up for his new movie.

Jonze wrote Her almost three years ago over a long New York winter. He worked from dozens of pages of his own notes, as well as the memory of a brief interaction he had with an artificial-intelligence computer program a decade ago in which “for the first 30 seconds, I had that buzz, like, It’s responding to me! Then it quickly fell apart and you realize, Here are the tricks, here’s how this works. But what if I could sustain that forever? What would that be like? I wanted to take that idea as far as I could possibly imagine and feel.”

Six months after production ends, Jonze and his editors are working on Her in a house in the Hollywood Hills that Ellison has turned into part of a postproduction compound for her filmmakers. It’s a Monday afternoon in February, the day after the 2013 Academy Awards, and he does not seem particularly aware of who won or lost. He’s happy with the way Her is looking; they’ve put together some scenes involving peripheral characters and made some design choices about a 3-D video game that serves as a refuge for Theodore. But he has already made one major decision, and it’s an unanticipated and painful one: He is going to have to recast his title character.

For any other movie, the discovery that you need to replace one of your principals after shooting is over could spell catastrophe—starting from scratch with just a script and a hope that the new footage will work better than the last shoot did. But Jonze seems unfazed. In the editing room, he says, it became apparent to him that despite Morton’s graceful and nuanced work, the relationship between Samantha and Theodore didn’t resonate the way he wanted it to. Jonze doesn’t seem upset about the need for a new actress—he noncommittally bats around a bunch of names, including that of Jennifer Lawrence, whose name is being batted around everywhere in Los Angeles the day after her Best Actress win. The unusual nature of the role has given him more maneuvering room than he’d have with an on-camera performance, and he isn’t hesitant about going back into production; he’s done it before. But having to replace an actress he admires stings, and even now, it’s the only aspect of his experience on the film that makes him wince. “Samantha Morton is one of the best actresses in the world,” he says. “We just couldn’t get there. Making a movie like this, in which a character only exists in her voice, in the reaction of a character onscreen, and in the viewer’s imagination—she had to exist just in the air—it’s hard to know what’s going to make that work. We didn’t know until we got deep into postproduction. But I think all I really want to say is … I want to honor Samantha for what she gave us and what she gave Joaquin. That’s a lot.”

In the spring, Jonze meets with Scarlett Johansson in New York, on her day off from the Broadway run of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and she signs on. He doesn’t want to have Johansson simply go into a postproduction facility and redub the dialogue; too much of Phoenix’s performance was calibrated to the rhythms of Morton’s delivery to make a simple line-for-line substitution effective. Instead, he will spend the next several weeks rebuilding the scenes between Theodore and the OS in a number of different ways, turning Samantha into a character with more tempest and volatility—a mind of her own, or the illusion of one—than she had exhibited before. Whereas Morton could sound maternal, loving, vaguely British, and almost ghostly, Johansson plays the role as younger, more impassioned, and with more yearning. She does her work on a dubbing stage, but sometimes Phoenix comes in to feed her his lines; evenutally he redubs part of his own performance as well. Jonze has always had an appetite for reimagining aspects of his films after he’s shot them. With this one, the casting change means he can do even more—the emotional variation in the multiple takes he did with Phoenix allows him to adjust and alter half the scenes in the movie without dismantling its structure or tossing out its story line, stitching in a new central performance without asking for weeks of expensive reshoots. As Jonze builds his movie again, what he wants is not quite Her 2.0. But with the hiring of Johansson—and, just as important, the cooperation of the very game Phoenix—he has an opportunity to revise not just a role but a relationship. He seizes it.

About a month before Jonze brings Her in front of the cameras again for a few days of additional photography, I meet him at a restaurant near his loft. At 43, he has started to look softly brushed by early middle age; he’s still slight, trim, and boyish, and he has the reedy, cracking voice of a teenager, but he’s no longer going to be mistaken for a kid who wandered onto the set. His bedheady blond hair is not quite as blond as it used to be—when I mention it later, he shoots me an e-mail saying, “I got more rhymes than I got gray hairs and that’s a lot because I got my share.” The line is from “Sure Shot,” a Beastie Boys track for which he directed the video almost two decades ago. “There was definitely a point in my thirties when I thought, Oh, wow, I’m not the youngest person on the set anymore,” he says. “But I like it. Working with younger artists is totally exciting.” He talks about going to Canada to help prepare the score for Her with Arcade Fire, noting that “most of them are ten years younger than me and they just feel like peers. Their process is very democratic. Anyone in the group can come up with an idea and play over someone else”—not, he notes with a wry grin, the way movie directors usually work.

That push and pull between collaboration and going it alone, between connectedness and solitude, isn’t just part of Jonze’s creative process—it’s right there in the text of his movies, all of which are, in some ways, about the limits of authorship. The protagonist of Being John Malkovich is a frustrated puppeteer who can only get people to do what he wants if they’re inanimate. Adaptation is about the mitosis of a screenwriter into twins, one a depressive who believes his sourness equals integrity and the other a cheerful panderer. And Wild Things’ Max writes a whole kingdom for himself only to discover that the weight of being the creator is too heavy. In one of the few overtly futurist flourishes in Her, Jonze has made his main character an expert ghostwriter—people hire Theodore to craft personal handwritten letters to their loved ones, and he becomes their voice for years on end. After Malkovich, one might have called that Kaufman-esque, but three movies later, it is nothing if not Jonzean: Theodore can script other people’s relationships beautifully, but only if he doesn’t let anyone see who he is.

Bounce this theory off Jonze and he will, in his polite way, let you know that all it does, in fact, is bounce off him. But all of his movies play with identity and emotional surrogacy—Charlie Kaufman invents a double for himself in Adaptation, and remember the “three-way” in Malkovich in which Catherine Keener tries to make love to John Malkovich’s semi-willing body and Cameron Diaz’s enthusiastic mind at the same moment? Her offers an astringent and unsentimental reprise that asks whether intimacy is possible in a world in which so many people pretend to be someone they’re not. Surely there’s some resonance there. Jonze, after all, was born Adam Spiegel; he not only gave himself a new identity as a teenager but also chose a name somebody famous already had. Since then, he’s invented other versions of himself. In fact, this magazine wrote in 1999 that “Jonze has been experiencing the world as somebody else for fifteen years, and now that he’s in danger of becoming famous, he’s been working more furiously than ever to stay behind his self-created mask.”

If Jonze’s plan is to let the work speak for itself, there’s no question that it’s going to speak in some interesting ways. The protagonist of Her and his creator are both fortyish men who are divorced from high-achieving women, and the decision to cast Johansson in a story of lonely-guy emotional displacement places Her in a kind of fascinating inadvertent dialogue with Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation.

Jonze doesn’t discuss his movies as if they were fragments of an emotional autobiography, but he no longer recoils, as he once did, from questions about the way he works. (He’s come a long way since the jokey DVD extra on Being John Malkovich that showed him clammily attempting to answer an interviewer’s questions for about four excruciating minutes before vomiting into a gutter.) Jonze says he’s pleased with his progress on the film—he’ll finish only a month or two later than his producer guessed he would a year earlier—but he knows he won’t have everything he needs until he goes back into production at the beginning of August. “Not reshoots,” he says. “What I would call them is newly imagined scenes and some new scenes that I had wanted to shoot originally but didn’t.” He grins. “Anyway.” Do you know that you need the new scenes? I ask.

“No,” he says. “But I don’t know that I don’t.”

There’s a truism that all movies are made at least three times, once in the writing, once on the set, and once in the editing room. Jonze believes in that process—especially phase three—and is not particularly defensive about it. “I’ll get there,” he says of his ability to cut his work down to size, “but often it takes me a while to pull things out.” The first cut of Her contained a good deal of what’s referred to in futuristic fiction as “world-building”—information and characters intended to gesture toward a larger environment. At one point, the movie was running two and a half hours.

Because Her was the first script Jonze had written alone, he may have been more attached to specific scenes than he usually is. “So we did something that we’ve always talked about doing but we’ve never done,” he says, “which is to give it to another director to edit.” When Jonze is stuck, he often looks to an eclectic group of friends and confrères—“peers,” he says, “that I rely on deeply for their opinions and their help.” Besides Kaufman, Fincher, and his Jackass cohorts, they include Keener, music-video director Chris Cunningham, writer-directors Nicole Holofcener and Miranda July, director Bennett Miller, who cast him in a small role in Moneyball, and Steven Soderbergh.

This time, it was Soderbergh he turned to—“He’s the smartest, fastest editor-filmmaker I know.” Jonze asked him if he’d be willing to take a weekend to look at the movie and do his own quick, gut-instinct cut. “He got the movie on a Thursday, and in 24 hours, he took it from two and a half hours to 90 minutes. We basically said, ‘Be radical, shock us,’ and it was awesome. He said, ‘I’m not saying this should be the cut of the movie, but these are things to think about.’ It was amazingly generous of him, and it gave us the confidence to lose some big things that I wasn’t ready to lose [before]. Even though we didn’t use that exact cut”—the movie now runs about two hours—“we were able to make connections between scenes out of connections he made. And making many of the cuts he suggested was a really good kind of pain.”

The final version of Her eliminates some intriguing material—a complicated backstory for one supporting character and a documentary-within-the-movie that featured Chris Cooper, whom Jonze directed to an Oscar in Adaptation. Ultimately, Jonze stripped Her of anything that might distract from the story he wanted to tell. “There are certain things I need to shoot,” he says, “even if nobody else thinks they’re going to be in the movie. But there are times when I need room to fall. And other times,” he says, “when I depend on my friends to save me.”

In conversation, Jonze tends to use we rather than I to describe the making of his movies—the we can mean pals, colleagues, his producers, or whichever of his team of collaborators were in the room when inspiration struck. But Her is as much of a solo act as he’s ever attempted. The first poster is an almost jarringly direct and vulnerable close-up of Phoenix looking into the camera. Under the title are the words a spike jonze love story. If that’s not putting yourself—or one of your selves—on the line, what is? “Every time I go to make something,” he wrote a couple of years ago in an essay called “The Working Light,” “I’m trying to discover … what I like and what I’m into. It’s like I’m figuring out who I am again.”

*This article originally appeared in the October 14, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

*The original version of this article incorrectly stated that Jonze directed a video for the song “Wax” by the band California. The video in question is by the band Wax, for the song “California.”