It’s a strange business, “reviving” something that’s been revived a few hundred times already: Sometimes you get evolution, and sometimes you just get diminishing returns. The easy rap on our latest batch of folk-rock blockbusters—those stunningly marketable Mumfords, Avetts, Lumineers & Co., with their waistcoats and unison shouts and tub-thumping hootenanny stage business—has always been that they fall too squarely in the latter category. And if you happen to take the “folk” they’re accused of reviving to mean, ultimately, a tradition of southern country-blues and Protestant hill-people music from roughly 100 years ago, then yes, you may find that there’s not a ton of the original left in there, apart from some gravelly affectations and banjos and a whole lot of suspenders. You may even grow uncharitable and conclude that a clutch of conventional rock types are belatedly adopting what amounts to tenant-farmer-chic gimmickry, or putting on arena-rock versions of “A Prairie Home Companion.” Music fans have had (and taken) our copious opportunities to, as they say, problematize certain aspects of this music, let alone just making jokes about the costume.

Then again: What if you take the “folk” they’re accused of reviving to mean the big folk revival—those bits of the fifties and sixties when hip collegiate audiences could put on their most Steinbeckian work shirts and head to the Village to hear kids with romantic-hobo stylings studiously fingerpick songs from about a half-century before that? While, nationwide, viewers of network variety shows could watch broadcasts of squeaky-clean crew-cut folksters in jug-band drag sing songs about railroads and refrains like “Hallelujah, I’m a bum”? In that case, you’d have to conclude that these new acts are pretty true to their source, arguments and anachronistic threads and all.

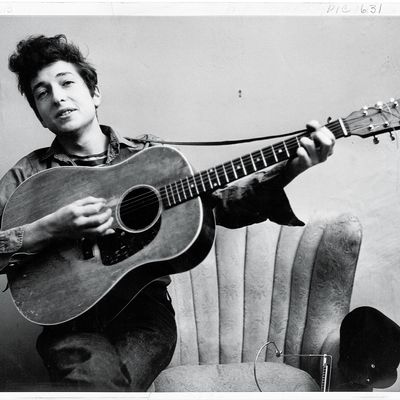

They could probably stand to have more argument. If you hear or read much about that sixties folk boom, you might notice that a huge share of the discussion surrounding the music is basically ideological, steeped in intellectual debate. You tend not to catch people talking about the music being pleasurable, seductive, funny, or infectious—it was, but that kind of rhetoric was forfeited to rock and roll, which was promptly written off as mindless nonsense for kids. No, the claims in favor of folk are always, across the years, that it is somehow right. That it has more depth and spirituality, more connection to history and the people, more political consciousness. It’s presented itself, often, as the “correct” thing for a serious-minded young person to enjoy, on about the same level that kale presents itself as the correct thing for a serious person to eat. And of course, ideology and serious-minded young people being what they are, you can pick apart the old folk scene into ideological camps: cheery pop groups, modern singer-songwriters, gritty blues moaners, academics for whom every folk song deserved an introduction explaining its history and provenance. I mean, this is a scene whose best-known single moment is the intellectualized furor sparked by Bob Dylan picking up an electric guitar at the Newport Folk Festival—how much more ideological sensitivity could you ask for?

That sensitivity seems inevitable, I think, because what we consider folk today might actually be a strange and particular thing. It’s not a living tradition, really. It’s more like a snapshot of a tradition—American rural music as it existed at the precise moment that someone thought to make recordings of it. At some point in the twenties or thirties, once enough of those recordings had been made, the whole thing was trapped in amber: It became, officially, the oldest version of rural-American “folk” music that anyone could go back to consult and imitate using their own ears. It became, almost by technological accident, the wellspring and the touchstone, leaving every generation of revivalists looking like a bunch of people holding blurry Polaroids of Eden and arguing over how to resurrect it. It’s like a cargo cult in reverse: Instead of “primitive” people coming across a modern object and surrounding it with elaborate mystical explanations, we get modern people discovering something traditional and erecting intellectual fetishes around it. And looking back to the “beginning,” even out of an earnest, uncalculated love of the music itself, is always going to be at least a little bit ideological, a response to whatever’s happened since.

I doubt there’s a whit of coincidence in the arrival of a vast commercial interest in folk’s trappings over the past few years. These are years during which the world of actual pop was well and truly reveling in all the qualities that inevitably make certain people crave the sound of a scratchy-throated dude with a tambourine tied to his foot—it’s been glitzy, youthful, synthetic, fashion-steeped, wealth-celebrating, club-oriented, idol-worshipping, ego-focused, “superficial,” and generally making hay of all those things that are both pop’s signature glories and the reasons people hate pop. (All of this to the extent that, you’ll notice, some of the year’s most talked-about pop songs are actually attempting to sneer at pop’s vapidity or materialism—“Royals,” “Thrift Shop,” “Hard Out Here.”) It creates an obvious market niche, a space for (if you’re inclined to be cynical) anyone who can swoop down with a woolly vest, some oil-stained signifiers of great authenticity, and a sound that essentially brands itself as Artisanal Handcrafted Music—or, if you’re inclined to be charitable, for music you can hear being brought into existence by human fingers and voice boxes, in a room full of breathable air.

Part of what makes the new chart-toppers work is that they’re essentially rock bands, not folk acts. They don’t seem to imagine, as musicians did in the sixties, that they can join in or engage with real folk traditions. They’ve evolved instead, straight into the dramaturgy of arena rock. Their music’s spotlit, and the songs are built around self-expression—the romantic rock star bathed in light and sweat and yowling cathartic anthems into the crowd. There are great shows of physical effort and muscle, a far cry from the laconic sing-along vibe of old folksingers. And yet somehow the appeal of these bands is still sort of communal: That’s why they’re always shouting in unison, and putting so much muscle into coaxing an arena-size racket out of old-timey instruments. At their best, they really do create that feeling of voices all raised together in a hushed room—an image of how music might be made that’s been steadily draining out of pop music, and maybe even church music, for decades. It’s a rare thing they’re gesturing at.

The funny part is that it’s such a small gesture, injected into music that’s otherwise following the rules of modern pop. It’s funny because this is the best we can do—arena rock with some gestures toward community, but none of the actual community that makes music genuinely “folk.” I mean, who, amid the cultural conditions of late capitalism, wants to deal in songs for the folk to learn and sing, rather than intellectual property that can be licensed out? How far can you get, in the modern world, treating your music as though it’s part of a tradition that belongs to the audience, rather than something you’re creating as an auteur? How would you even go about trying? If you want to talk about the diminishing returns of folk, this is the fascinating one: As soon as we started recording this stuff, it became awfully difficult for it to exist. So now our revivalists live in a world of authorship and property, documents and influences, and every once in a while they all shout “Hey” in unison, a faint echo of the proposition that music can also work differently.

*This article originally appeared in the December 9, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.