1. Defining a new form.

We live in the age of the selfie. A fast self-portrait, made with a smartphone’s camera and immediately distributed and inscribed into a network, is an instant visual communication of where we are, what we’re doing, who we think we are, and who we think is watching. Selfies have changed aspects of social interaction, body language, self-awareness, privacy, and humor, altering temporality, irony, and public behavior. It’s become a new visual genre—a type of self-portraiture formally distinct from all others in history. Selfies have their own structural autonomy. This is a very big deal for art.

Genres arise relatively rarely. Portraiture is a genre. So is still-life, landscape, animal painting, history painting. (They overlap, too: A portrait might be in a seascape.) A genre possesses its own formal logic, with tropes and structural wisdom, and lasts a long time, until all the problems it was invented to address have been fully addressed. (Genres are distinct from styles, which come and go: There are Expressionist portraits, Cubist portraits, Impressionist portraits, Norman Rockwell portraits. Style is the endless variation within genre.)

These are not like the self-portraits we are used to. Setting aside the formal dissimilarities between these two forms—of framing, of technique—traditional photographic self-portraiture is far less spontaneous and casual than a selfie is. This new genre isn’t dominated by artists. When made by amateurs, traditional photographic self-portraiture didn’t become a distinct thing, didn’t have a codified look or transform into social dialogue and conversation. These pictures were not usually disseminated to strangers and were never made in such numbers by so many people. It’s possible that the selfie is the most prevalent popular genre ever.

Let’s stipulate that most selfies are silly, typical, boring. Guys flexing muscles, girls making pouty lips (“duckface”), people mugging in bars or throwing gang signs or posing with monuments or someone famous. Still, the new genre has its earmarks. Excluding those taken in mirrors—a distinct subset of this universe—selfies are nearly always taken from within an arm’s length of the subject. For this reason the cropping and composition of selfies are very different from those of all preceding self-portraiture. There is the near-constant visual presence of one of the photographer’s arms, typically the one holding the camera. Bad camera angles predominate, as the subject is nearly always off-center. The wide-angle lens on most cell-phone cameras exaggerates the depth of noses and chins, and the arm holding the camera often looks huge. (Over time, this distortion has become less noticeable. Recall, however, the skewed look of the early cell-phone snap.) If both your hands are in the picture and it’s not a mirror shot, technically, it’s not a selfie—it’s a portrait.

Selfies are usually casual, improvised, fast; their primary purpose is to be seen here, now, by other people, most of them unknown, in social networks. They are never accidental: Whether carefully staged or completely casual, any selfie that you see had to be approved by the sender before being embedded into a network. This implies control as well as the presence of performing, self-criticality, and irony. The distributor of a selfie made it to be looked at by us, right now, and when we look at it, we know that. (And the maker knows we know that.) The critic Alicia Eler notes that they’re “where we become our own biggest fans and private paparazzi,” and that they are “ways for celebrities to pretend they’re just like regular people, making themselves their own controlled PR machines.”

When it is not just PR, though, it is a powerful, instantaneous ironic interaction that has intensity, intimacy, and strangeness. In some way, selfies reach back to the Greek theatrical idea of methexis—a group sharing wherein the speaker addresses the audience directly, much like when comic actors look at the TV camera and make a face. Finally, fascinatingly, the genre wasn’t created by artists. Selfies come from all of us; they are a folk art that is already expanding the language and lexicon of photography. Selfies are a photography of modern life—not that academics or curators are paying much attention to them. They will, though: In a hundred years, the mass of selfies will be an incredible record of the fine details of everyday life. Imagine what we could see if we had millions of these from the streets of imperial Rome.

2. What they say.

I’ve taken them. (I used to take self-shots with old-fashioned cameras and send the film off to be developed, then wait by the mailbox, antsy that my parents would open the Kodak envelope and find the dicey ones. These, unlike selfies, were not for public view.) You’ve taken them. So has almost everyone you know. Selfies are front-page news, subject to intense, widespread public and private scrutiny, shaming, revelation. President Obama caught hell for taking selfies with world leaders. Kim Kardashian takes them of her butt. The pope takes them [1]. So did Anthony Weiner; so did that woman on the New York Post’s front page who, perhaps inadvertently, posted pics of herself with a would-be suicide on the Brooklyn Bridge in the background. James Franco has been called “the selfie king.” [2] A Texas customer-service rep named Benny Winfield Jr. has declared himself “King of the Selfie Movement.” [3]

Many fret that this explosion of selfies proves that ours is an unusually narcissistic age. Discussing one selfie, the Post trotted out a tired line about “the greater global calamity of Western decline.” C’mon: The moral sky isn’t falling. Marina Galperina, who with fellow curator Kyle Chayka presented the National #Selfie Portrait Gallery, rightly says, “It’s less about narcissism—narcissism is so lonely!—and it’s more about being your own digital avatar.” Chayka adds, “Smartphone selfies come out of the same impulse as Rembrandt’s … to make yourself look awesome.” Franco says selfies “are tools of communication more than marks of vanity … Mini-Mes that we send out to give others a sense of who we are.” Selfies are our letters to the world. They are little visual diaries that magnify, reduce, dramatize—that say, “I’m here; look at me.”

Unlike traditional portraiture, selfies don’t make pretentious claims. They go in the other direction—or no direction at all. Although theorists like Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes saw melancholy and signs of death in every photograph, selfies aren’t for the ages. They’re like the cartoon dog who, when asked what time it is, always says, “Now! Now! Now!”

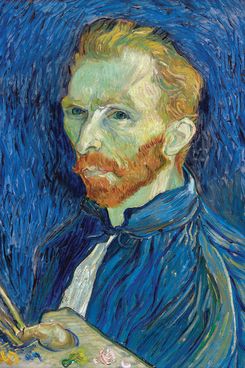

We might ask what art-historical and visual DNA form the selfie’s roots and structures. There are old photos of people holding cameras out to take their own pictures. (Often, people did this to knock off the last frame in a roll of film, so it could be rewound and sent to be processed.) Still, the genre remained unclear, nebulous, and uncodified. Looking back for trace elements, I discern strong selfie echoes in Van Gogh’s amazing self-portraits [4]—some of the same intensity, immediacy, and need to reveal something inner to the outside world in the most vivid way possible. Warhol, of course, comes to mind with his love of the present, performative persona and his wild Day-Glo color. But he took his own instant photos of other subjects, or had his subjects shoot themselves in a photo booth—both devices with far more objective lenses than a smartphone, as well as different formats and depths of field. Many will point to Cindy Sherman. But none of her pictures is taken in any selfie way. Moreover, her photographs show us the characters and selves that exist in her unbridled pictorial imagination. She’s not there.

Maybe the first significant twentieth-century pre-selfie is M. C. Escher’s 1935 lithograph Hand With Reflecting Sphere. Its strange compositional structure is dominated by the artist’s distorted face, reflected in a convex mirror held in his hand and showing his weirdly foreshortened arm. It echoes the closeness, shallow depth, and odd cropping of modern selfies. In another image, which might be called an allegory of a selfie, Escher rendered a hand drawing another hand drawing the first hand. It almost says, “What comes first, the self or the selfie?” My favorite proto-selfie is Parmigianino’s 1523–24 Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, seen on the title page of this story. All the attributes of the selfie are here: the subject’s face from a bizarre angle, the elongated arm, foreshortening, compositional distortion, the close-in intimacy. As the poet John Ashbery wrote of this painting (and seemingly all good selfies), “the right hand / Bigger than the head, thrust at the viewer / And swerving easily away, as though to protect what it advertises.”

Everyone has their own idea of what makes a good selfie. I like the ones that metamorphose into what might be called selfies-plus—pictures that begin to speak in unintended tongues, that carry surpluses of meaning that the maker may not have known were there. Barthes wrote that such images produce what he called “a third meaning,” which passes “from language to significance.”

I’m not talking about cute contradictions, unintended parody, nip slips, moose knuckles. Everyone’s subject to these unveilings. No, I’m talking about more unstable, obstinate meanings that come to the fore: fictions, paranoia, fantasies, voyeurism, exhibitionism, confessions—things that take us to a place where we become the author of another story. That’s thrilling. And something like art.

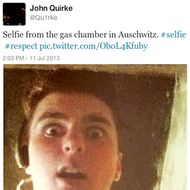

Take, for example, a photo posted last July by John Quirke [5]. The picture itself is nothing; a strapping twentysomething, shot from below in what looks like a basement. His mouth is agape, his eyes wide open. He wears headphones. The impact of the picture comes in Quirke’s tag: “Selfie from the gas chamber in Auschwitz.” The picture exceeds itself, vaults outside meaning, becoming what Barthes described as “locatable but not describable.” Image and text merge in ways that add more oomph. There are similar pictures of people at Chernobyl, in front of car wrecks, with a suicide taking place over one’s shoulder. Another selfie is captioned “The photos are of me at Treblinka …”

We can’t merely dismiss these as violations of sanctified spaces or lapses of judgment. Atget photographed crime scenes. War correspondents catch images of people being blown to bits. Many of us have taken pictures of homeless people, Dealey Plaza in Dallas, an electric chair, the hole left by the World Trade Center. I photographed the second tower falling. The new twist of the selfie is that we’re in these pictures. (I didn’t include myself in that one.) Many are in bad taste, and some indulge in shock value for shock value’s sake, but they are, nevertheless, reactions to death, fear, confusion, terror, annihilation.

They can, at times, evince our need to unsee things. On the pickup site Grindr, people use as their avatars selfies taken in Berlin’s Holocaust memorial. Captions include “Aussie on holidays :-) Lets [sic] have some fun” and “How many times did you jerk off.” We know our sex drives are with us always, but so is something just as archaic: taboo. After making an idiotic knock-knock joke in court, George Zimmerman’s defense lawyer, Don West, took a selfie in a car with his daughters eating ice-cream cones [6]. The chilling caption is by his daughter Molly: “We beat stupidity celebration cones,” followed by emoticons of a ringing bell, a grinning face, and the hashtag “#dadkilledit.” The world grows dark before our eyes in selfies like these.

3. What they don’t say (but do reveal).

The bizarre side of the mirror is Kim Kardashian’s now-famous picture of her ass and side-boob [7]. The pose is utterly banal; she’s like millions of others admiring themselves in mirrors, trying to show some part of their body to best advantage. Kardashian goes a step further. As she gets everything to show just right while admiring her own image in the phone, the third meaning that pops out is not her body. It’s how weirdly stage-managed the scene is. Her body is blatantly visible while her décor is carefully blocked off by Japanese screens. Her ass-crack is intentionally outlined, but she doesn’t want us to see her sofa. Kim has even authored four rules for the perfect selfie: “Hold your phone high [as you shoot]; know your angle; know your lighting; and no duckface!”

Equally idiotic winds of third meaning blow through other recent celebrity selfies. Seventy-year-old Geraldo Rivera’s selfie shows him gazing at his own stomach muscles in a bathroom mirror [8], naked but for a low-slung towel. Unlike third meanings that tell us something new, selfies like this confirm what we already know. (Here, that Geraldo is a self-involved publicity-loving hound dog.) It’s no different from those celebrity porn films that are self-released accidentally-on-purpose, either to remake images or out of simple sociopathology. Then there’s the subcategory of what I call the Selfie Sublime: an extraordinary moment, photographed to incorporate the shooter’s own astonishment. We see it in astronaut Aki Hoshide’s selfie hovering in space [9], his silver helmet showing none of his features, the Sun behind him, the Earth reflected in his visor. In its counterpart, the Selfie Terrible Sublime, we see not beauty but agony. On December 11, Ferdinand Puentes photographed himself in the beautiful blue ocean off the shore of Molokai, in Hawaii, seconds after his small passenger plane crashed and began to sink [10]. The look on his face is spectral, terrified, ecstatic, eerie, vertiginous. This is someone photographing himself lost and imperiled, recording and sending off what he knows might be his final moments. After being rescued, Puentes said that when they heard sirens and bells going off in the plane and the water coming up fast, “everyone knew what was going on.” While looking at the selfie, he repeated, “It hurts.” We know this from his selfie.

Soon, from somewhere in the digital universe, came comparisons to Puentes’s with selfies taken by gamer avatars in Grand Theft Auto 5 [11] that depict themselves with catastrophes. Here, people have created fictional figures that mimic what we do, and amazingly enough, the genre’s earmarks are often present in their avatars’ self-shots: the telltale raised shoulder, the close-in view, the bad camera angle, and the stare.

Back on Earth, the most famous selfie of 2013 has never actually been seen. When President Obama, British prime minister David Cameron, and Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt took a group selfie at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service [12], we saw only Roberto Schmidt’s photograph of them doing so. This was a kind of Las Meninas selfie—akin to Velázquez’s astonishing royal-portrait-plus-self-portrait, which ricochets among the subjects, switching up who’s seeing whom from where. Many bellowed about the Obama selfie’s gall and pomposity. Its third meaning, however, is far more pedestrian and human: It’s the invisible thought balloon over the subjects. “It is totally incomprehensible, even to us, to be us,” they are saying, “or to be us, being here.” It pictures three famous people engaged in what Hegel called “picture-thinking.” Or selfie-thinking.

Prank selfies abound; most are banal, fun Jackass-type pictures. Although there are oddities here as well, like the guy who quietly crawled atop a bathroom stall and photographed himself with the unaware person sitting on a toilet below. There are antic photos of, say, someone doing a headstand with his head in a fishbowl or break-dancing on a sink. A lot of quasi-performance-art selfies are better than a lot of so-called real art. People throwing computers timed to do something—light up, blow up, whatever—in midair and then photographing themselves as the event unfolds, or holding a giant copy machine up to a mirror. There’s a selfie-plus of a guy and his dog taken by—wait for it—the dog! [13] Of course, there are also selfies of people performing oral sex. My predilections lean toward Balzacian selfies, pictures with strange stuff visible in the background—the ones where we see the books on the coffee table, items on the shelves, posters on the walls, leftovers in the kitchen. All these things let me think I’m getting some peek into the person’s unseen life. The less publicity-driven (non-Kardashian) celebrity Instagram and Twitter feeds are good for this, because those lives are usually closed off to us, and the small details seem extra-revelatory. How much they have been staged, of course, we will never know.

4. Art history, art future.

I’m far from the first to say the selfie is something significant. Way back in 2010, the artist-critic David Colman wrote in the New York Times that the selfie “is so common that it is changing photography itself.” Colman in turn quoted the art historian Geoffrey Batchen saying that selfies represent “the shift of the photograph [from] memorial function to a communication device.” What I love about selfies is that we then do a second thing after making them: We make them public. Which is, again, something like art.

Whatever the selfie represents, it’s safe to say it’s in its Neolithic phase. In fact, the genre has already mutated at least once. Artist John Monteith has saved thousands of anonymous images from the selfie’s early digital era, what Monteith calls the “Wild West days” of selfies. These are self-portraits taken with crude early webcams, showing weird coloration, hot spots, bizarre resolution. Posted online starting around 1999, they have mostly evaporated into the ethersphere. The “aesthetic” of these early selfie calling cards and come-ons is noticeably different from today’s, because the cameras were deskbound. Settings are more private, poses more furtive, sexual. Tics crop up: women showing new tongue piercings, shirtless men with nunchucks. They seem as ancient as photographs of nineteenth-century Paris.

It’s easy to project that, with only small changes in technology and other platforms, we will one day see amazing masters of the form. We’ll see selfies of ordeal, adventure, family history, sickness, and death. There will be full-size lifelike animated holographic selfies (can’t wait to see what porn does with that!), pedagogical and short-story selfies. There could be a selfie-Kafka. We will likely make great selfies—but not until we get rid of the stupid-sounding, juvenile, treacly name. It rankles and grates every time one reads, hears, or even thinks it. We can’t have a Rembrandt of selfies with a word like selfie.

*This article originally appeared in the February 3, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.