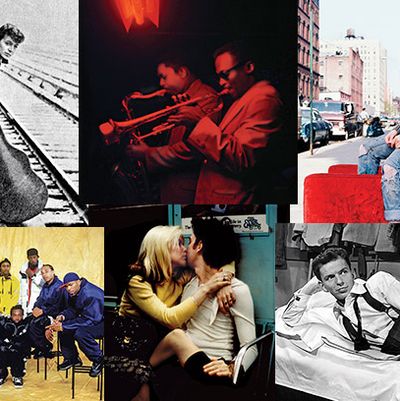

This is not the history of popular music in New York, but a history—an impressionistic, anecdotal, suggestive, but by definition incomplete survey of the past 100 years of New York pop, focusing on key figures and watershed events. Sharp readers will find that many illustrious musicians and moments—even whole genres—have been left on the cutting-room floor. But we’ve tried to convey the crazy-quilt variety of New York’s pop music, to highlight telling vignettes, and, where possible, to let the musicians speak for themselves. (Plus, check back throughout the week for extended testimonies from Burt Bacharach, Grandmaster Flash, Thurston Moore, and more.)

*This article appeared in the March 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

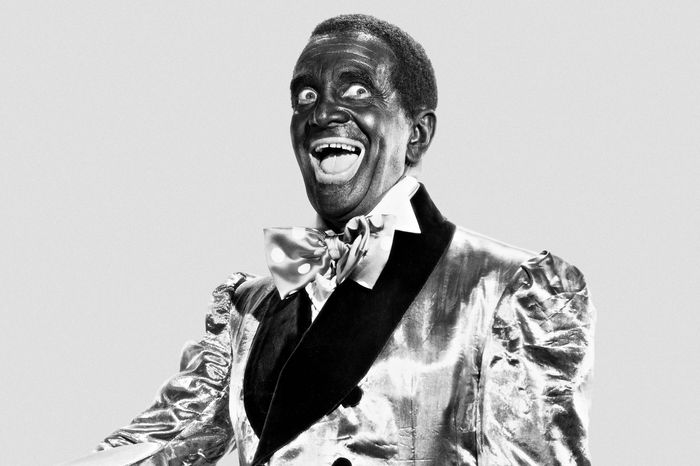

In 1918, when Al Jolson was booked to perform at the Winter Garden on Broadway between 50th and 51st Streets, the theater’s owners, J. J. and Lee Shubert, installed a ramp that ran down the center of the aisle so he could get right next to the audience. Jolson had been making box-office-breaking runs at the venue for nearly a decade. That year, the vehicle was Sinbad, a dopey musical retelling of the Arabian Nights that involved Long Island socialites, a crystal ball, and a bunch of elaborately Orientalist song-and-dance numbers. The plot, the staging—none of it really mattered. Sinbad was the Al Jolson Show, and in 1918, Jolson was at the height of his superstardom, the most popular singer on the planet.

The Winter Garden was a “classy” uptown venue—but, as usual, Jolson brought the house down with an act that retained the grit and funk of the downtown Rialto, singing fanatically sentimental songs behind a mask of garish burned cork. Today, we rightly recoil from blackface—but our aversion to the minstrelsy should not cause us to mistake the genius of this minstrel. Jolson was a dynamo like few performers before or since. His art expressed itself in extremes: high decibels, outsize gestures, madcap comedy, grotesque gesticulations, torrents of schmaltz. His style was about volume and intensity first; in those days before the microphone, you had to project to reach the cheap seats. But Jolson also specialized in vocal effects: slurred phrases, sobs, stretched vowels, horselike whinnying, and abrupt changes in register, moving manically from full-throated belting to talk-singing and back again.

His vocal athleticism was matched by a feverish physical presence. He bragged to reporters that he ran the equivalent of a marathon in a typical performance. Jolson’s trademark move—dropping to his knees with arms spread wide—was pure Broadway hokum, but it was also an erotic gesture and a supplication: an attempt to collapse distance, to smash the fourth wall, to literally reach the audience. Jolson confessed that he liked to shake his head so that his perspiration doused theatergoers in their seats. —Jody Rosen

“I made up a character named Soph—it was an homage more than an impersonation. There were other women working at the time who did what she did: Mae West, in her way, who sang and told stories, and Belle Barth and Frances Faye and Rusty Warren. The character I made up was a little bit of a tribute to those kind of bighearted broads who sang and told stories. They were very risqué. I wanted to be able to tell their jokes, but some of them were so appalling. I felt that if I took credit for them I would be diminished in some way, so I made up a persona that I could hide behind. And people recognized her as a kind of iconic character from their own childhoods. Those performers had been on television. They had been in the public consciousness. Their parents brought home those records—in brown paper wrappers, you know? It was a part of their growing up. It was very Jewish, and very Catskills-y.” —Bette Midler

Photo: 2002/Daily News, L.P. (New York)

Watch Your Step was the first musical comedy fully scored by Irving Berlin, the archetypal New York City songwriter. It was also, you might say, the first New York City musical. Of course, there had been countless shows staged in the city before; Broadway had been synonymous with musical theater since the 1830s. But with Watch Your Step, Berlin sought not only to write New York songs but to represent the city sonically: to make music that sounded like the clangorous, cacophonous metropolis of 1914.

He did it with rhythm. The songwriter’s monster 1911 hit “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” established ragtime as America’s pop-music lingua franca and earned Berlin the title of “Ragtime King.” Watch Your Step, accordingly, was billed as a “syncopated musical,” a show that brought the rhythms—the racket—that had ignited dance halls across the country to the august Broadway stage. A critic in the New York Dramatic Mirror called Watch Your Step “the noisiest affair I have ever attended”; the New York World praised the show for introducing “cow bells, tin pans, squawkers, rattles, and other election-night musical instruments into the modern dance orchestra.” The score showcased Berlin’s range: There were love ballads, minstrel-show numbers, comic novelty songs, and, of course, a lot of dance music. At the center of it all was the superstar husband-and-wife team of Vernon and Irene Castle, who gentrified saucy dance steps like the Grizzly Bear and the Turkey Trot for mainstream consumption. The show was a smash, launching Berlin’s Broadway career, which would continue into the 1960s. It was also, in its polite way, a generational gauntlet—notice served that American popular music had arrived to lay waste to fusty old-world sounds. The blowout Act II finale, “Ragtime Opera Medley,” drove the point home: “Aida / We’re gonna chop up your meter / We’re getting tired of you and so / Here’s where we’re going to / Hurdy-gurdy Mister Verdi.” —J.R.

Photo: © Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

Five decades before the phrase was coined, a Ziegfeld Follies girl with a mediocre voice embodied the spirit of rock and roll. One of her many lovers, the mystic Aleister Crowley, memorably captured her appeal: “She is like the hashish dream of a hermit who is possessed of the devil. She cannot sing, as others sing; or dance, as others dance. She simply keeps on vibrating, both limbs and vocal cords without rhythm, tone, melody, or purpose … I feel as if I were poisoned by strychnine … I jerk, I writhe, I twist, I find no ease … She is perpetual irritation without possibility of satisfaction, an Avatar of sex-insomnia. Solitude of the Soul, the Worm that dieth not; ah, me!”

When George Gershwin first popped up on Tin Pan Alley, he instantly stood out. The songwriters’ row was full of grizzled street-smart types. Gershwin, who often collaborated with his older lyricist brother Ira, had street-kid bona fides, but his piano chops were, in Alley parlance, “high-class”; his musical knowledge encompassed the usual pop ditties but also Beethoven and Chopin and Liszt. Then came “Rhapsody in Blue.” Gershwin, just 25 at the time, was commissioned to write a piece for piano and jazz band. The result was a culture crash the likes of which had never been heard before, elevating American vernacular blues and jazz into the rarefied realm of European orchestral music—or was it bringing classical music down to earthier territory? No matter: “Rhapsody in Blue” was beautiful and thrilling; from its first moments—the famous opening clarion call, a wailing, wavering, trombonelike glissando played on a clarinet—it obliterated the outdated high-low distinctions. —J.R.

Photo: 2011 Getty Images

On May 23, 1921, an unusual musical revue premiered at Daly’s 63rd Street Theatre. Shuffle Along had a silly plot about a mayoral race and municipal corruption in the fictional metropolis of Jimtown, USA. What set the show apart was its music, co-composed by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, whose thrillingly brassy, syncopated sound was summed up by the title of the song that kicked the evening off: “I’m Just Simply Full of Jazz.” Then there was the all-black cast, a veritable Who’s Who of leading African-American performers of the day, including such titans as Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, and Adelaide Hall. The show’s breakout star, though, was Florence Mills, a scrawny 25-year-old Washingtonian making her New York debut. Mills stole the show with “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love,” which she brought to life with an electrifying, slow-burn sauciness that seemed improbable for a performer with her nymphlike stage presence. As Sissle recalled five decades later, “She was Dresden china, and she turned into a stick of dynamite.” —J.R.

Photo: Anthony Barboza

It makes sense that James P. Johnson wrote “Charleston,” the anthem of the Jazz Age. Piano players, capable of turning any bar or living room into an all-night party, had the run of the city. “When a real smart ‘tickler’ would enter a place,” he said, “say, in winter, he’d leave his overcoat on and keep his hat on, too. We used to wear military overcoats, or a coat like a coachman’s—blue, double-breasted, fitted to the waist and with long skirts … Some ticklers would sit sideways at the piano, cross their legs, and go on chatting with friends nearby. It took a lot of practice to play this way. Then, without stopping the smart talk or turning back to the piano, he’d attack without warning, smashing right into the regular beat of the piece. That would knock them dead.” Johnson modernized the piano’s left-hand rhythms, turning ragtime’s oompah into the driving, danceable power of stride. But “Charleston” came from something older. The song’s rhythm, he said, was based on “a regular cotillion step” from South Carolina. Included in the 1923 Broadway show Runnin’ Wild, the old plantation dance swept the world. —John Homans

Photo: Time & Life Pictures

Before Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan—before, for that matter, Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston and Beyoncé—there was Ethel Waters, the imperial blues singer and Harlem Renaissance leading light who showed that an African-American woman could move from “race music” marginalization to mainstream pop stardom. The song that put her over the top was “Am I Blue?,” which, despite the title, wasn’t a blues at all but a vaguely bluesy pop torch song, written by Tin Pan Alley hacks Harry Akst and Grant Clarke for the 1929 film On With the Show! The number was staged in heinous Hollywood minstrel-show fashion: Waters sings on a slave-plantation stage set while gripping a bale of cotton. But her performance blasted through the surrounding racist kitsch, showcasing Waters’s vibrant and expressive voice, her masterful phrasing, and her queenly diction, which would put the most exacting opera prima donna to shame. “I’m just a woman that’s only human / One you should feel sorry for,” Waters sang—but it was hard to feel anything but wonder at her regal presence. —J.R.

Photo: 1929 Gilles Petard

At first, swing clarinetist Benny Goodman, who’d grown up poor and Jewish, resisted producer John Hammond’s entreaties to record with black musicians, great as he knew they were. “If it gets around that I recorded with colored fellows,” Goodman said, “I won’t get another job in this town.” But after one long night of jamming at the Queens home of singer Mildred Bailey and vibraphonist Red Norvo, Teddy Wilson’s elegant, Champagne-bubbling piano style, so perfectly suited to Goodman’s own playing, won him over. “Teddy and I began to play as though we were thinking with the same brain,” Goodman said. “It was a real kick.” And thus the most popular band of the swing era was integrated. —J.H.

Photo: Time & Life Pictures

Open-minded and exploratory in the way that certain children of privilege can be, John Hammond had a catalytic effect on the New York music scene for a half-century, in multiple genres as well as in politics. In the 1930s, he changed the course of jazz as much as any single musician, putting together bands, importing artists from the hinterlands, and marking the music with his own sensibility. Later, as a long-in-the-tooth producer at Columbia, he championed rock and folk artists whose talents younger colleagues simply couldn’t recognize. It seems cognitively dissonant that the great-great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt could have spent so long on the musical vanguard—but the list of musicians whose careers he transformed tells the story: Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Teddy Wilson, Charlie Christian, Count Basie, Aretha Franklin, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Fletcher Henderson, Lionel Hampton, Joe Venuti, Benny Carter, Robert Johnson, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Babatunde Olatunji.

Hard-living daughter of a prostitute who turned tricks herself, Billie Holiday had hardly dreamed of a musical career—then, at the Log Cabin Club in Harlem, she opened her mouth to sing. “One day we were so hungry we could barely breathe. I started out the door. It was cold as all hell, and I walked from 145th to 133rd … going in every joint trying to find work … I stopped in the Log Cabin Club, run by Jerry Preston … told him I was a dancer. He said to dance. I tried it. He said I stunk. I told him I could sing. He said sing. Over in the corner was an old guy playing the piano. He struck “Trav’lin,” and I sang. The customers stopped drinking. They turned around and watched. The pianist … swung into “Body and Soul.” Jeez, you should have seen those people—all of them started crying. Preston came over, shook his head, and said, “Kid, you win.” —Billie Holiday, Downbeat Magazine

In 1938, composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Edgar “Yip” Harburg were asked to write a score for a movie musical based on L. Frank Baum’s children’s classic The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). The songwriters were seasoned pros; Arlen was Tin Pan Alley’s foremost pop-blues composer, Harburg the wit behind “April in Paris” and the classic Great Depression lament “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” But this was a tricky assignment. Baum’s book was a strange, sprawling fantasy about a Kansas farm girl who travels to a magical land. Critics had often read it as a Gilded Age political allegory; Baum had always insisted it was a fairy tale. The dramatis personae included talking lions and scarecrows, witches, flying monkeys, and little people. What kind of music could a couple of Jewish Tin Pan Alley pros come up with for this mishegoss?

The answer, it turned out, was one of the greatest—possibly the greatest—pop songs of all time. Seven decades later, the movie’s centerpiece, “Over the Rainbow,” remains the essence of pop-ballad splendor. With its cresting rainbow-arc melody and startling octave leaps, Arlen’s tune feels both magical and inevitable. Harburg’s lyric—“Somewhere over the rainbow / Way up high / There’s a land that I heard of / Once in a lullaby”—is a feat of artful artlessness, an expression of yearning that works both in context, as the interior monologue of Dorothy from Kansas, and for everyone, for all audiences. Years later, recalling the struggle to write the song, Harburg praised Arlen’s flair for the dramatic. “One person is born with a sense of dramaturgy, another not … It’s got to be something that moves an audience, either to laughter or to tears.” —J.R.

Photo: 2004 Getty Images

Both Fats Waller and Andy Razaf grew up in Harlem, and both were in the thick of the action in the 1920s, when their home turf became the vibrant center of black cultural and intellectual life. But it wasn’t until the end of that decade that Waller (singer, songwriter, stride pianist, clown prince nonpareil) and Razaf (lyricist and poet) began collaborating. The results were magic. Waller and Razaf brought the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance—the wit and urbanity and sass and effortless cool—into the American mainstream, merging that distinctly uptown vibe with the commercially savvy craftsmanship of Tin Pan Alley, where Razaf had been toiling since he dropped out of school at 16. Listening to hits like “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” “Ain’t Cha Glad?,” and “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now,” audiences who’d never been north of 96th Street—who’d never been east of the Mississippi—could imagine they’d scored an invite to the world’s hippest and most exclusive Harlem rent party. —J.R.

Photo: 1935 Gilles Petard

Yale-educated and independently wealthy, he lived with a flamboyant Manhattan style that was reflected in his music, as in this lyric from his 1936 song “Down in the Depths.” While the crowds at El Morocco punish the parquet / And at 21 the couples clamor for more / I’m deserted and depressed / In my regal eagle’s nest / Down in the depths of the 90th floor.

Photo: © Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

New York has had its share of illustrious house bands—the Roots on Jimmy Fallon’s show, the Velvet Underground at the Factory, Leonard Bernstein’s New York Philharmonic—but no musical residency holds a candle to Duke Ellington’s three-year run at the Cotton Club, from late 1927 to early 1931. The city was at the height of its interwar heyday: The skyline was shooting up, along with flappers’ hemlines; bons mots were flying across the Algonquin Round Table; and home runs were sailing off the bats of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig into the original Yankee Stadium’s bleachers. But it was the music made by Ellington and his orchestra at the Cotton Club in Harlem that best captured the beauty and ferment of that Roaring Twenties apotheosis. The Cotton Club was founded as a magnet for slummers, showcasing entertainment by black musicians and dancers for a strictly whites-only crowd. Ellington was hired to give those white thrill-seekers what they came for—exotic “jungle music”—but from the first note his orchestra played, in its December 4, 1927, revue, it offered something else: “Creole Love Call,” “Black and Tan Fantasy,” and other deathless songs that transmuted African-American experience into symphonic music as rich as any this country has ever produced. —J.R.

Photo: Time & Life Pictures

His dust-bowl wanderings fueled his music, but New York City was where he felt most at home: “I walked along, the day just leaving out over the tops of the tall buildings, and sifting through the old scarred chimneys sticking up. Thank the good Lord, everybody, everything ain’t all slicked up, and starched and imitation. Thank God, everybody ain’t afraid. Afraid in the skyscrapers, and afraid in the red-tape offices, and afraid in the tick of the little machine that never explodes, stock-market tickers, that scare how many to death, ticking off deaths, marriages, and divorces, friends and enemies; tickers connected and plugged in like jukeboxes, playing the false and corny lies that are sung in the wild canyons of Wall Street.” —Woody Guthrie, Bound for Glory

Photo: Eric Schaal/Time Life Pictures

Maybe what is called modernism began to emerge with the invention of the steam engine. Perhaps it was with Darwin, the publishing of Madame Bovary, or Picasso. But it peaked on West 118th Street in Harlem, which is where Thelonious Monk, with melodic input from drummer Kenny Clarke, wrote and first played “Epistrophy” in 1941. Originally titled “Fly Rite” and then “Iambic Pentameter,” the song was named for the Greek epistrophe, meaning the repetition of the same word or sound at the end of successive sentences or musical phrases. The idea is a perfect distillation of the pianist’s style, except that Monk, most of whose neighborhood was bulldozed by Robert Moses to make way for Lincoln Center, somehow never quite repeated anything, at least not the way he played it before. Probably the single greatest composer in jazz history, Monk wrote a lot of famous tunes. But it was with “Epistrophy” that jazz fully embraced the direction that would lead to a sonic revolution. The first of Monk’s major works, the tune bridges the swing elements of jazz’s popular-music phase with the foreboding of a world already headlong into another war, as well as the ongoing anguish of the black American. Played bouncily—an irony Monk often employed—“Epistrophy” remains a low-slung dance number, but it is a dance set in an underworld. Its message is simultaneously stark and subversively joyful. —Mark Jacobson

Photo: Herman Leonard/© Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

“Three in the morning the doorbell rang and I opened it as far as the latch chain permitted. There was Bird, horn in hand, and he says, “Let me in, Diz, I’ve got it; you must hear this thing I’ve worked out.” I had been putting down Bird’s solos on paper, which is something Bird never had the patience for himself. “Not now,” I said. “Later, man, tomorrow.” “No,” Bird cried. “I won’t remember it tomorrow; it’s in my head now; let me in, please.” From the other room, my wife yelled, “Throw him out,” and I obediently slammed the door in Bird’s face. Parker then took his horn to his mouth and played the tune in the hallway. I grabbed a pencil and paper and took it down from the other side of the door.” —Dizzy Gillespie

Photo: Herman Leonard/© Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

Alan Freed might have been the first person to mention the phrase “rock and roll,” but a good argument can be made that Louis Jordan was the first to play it, on the stage of the Apollo Theater. After a sojourn playing his alto sax with Chick Webb at the iconic Savoy Ballroom, Jordan and his Tympany Five tore things up at the Apollo, on and off, for the next 25 years. It was at the Apollo that he first introduced many of his fabulously titled tunes like “The Chicks I Pick Are Slender, Tender and Tall,” “G.I. Jive,” and “Somebody Done Changed the Lock on My Door,” along with the famous hits “Caldonia (What Makes Your Big Head So Hard?),” “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie,” and “Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens.” Locked out of most segregated venues (he spent many a night on the all-black TOBA circuit, which stood for Theater Owners Booking Association, but it was quickly renamed Tough on Black Asses), Jordan was making what were often characterized as “race” records. But plenty of rock and roll’s official founding family, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bill Haley—all of whom acknowledge their debts—knew what they were hearing. Jordan maintained something of a love-hate relationship with the Apollo, complaining that the place was “a filthy theater. The same dirt was there from year to year.” It was there that another Apollo star, James Brown, saw Jordan. Asked what influence Jordan’s high-flying act had on him, Brown said, “He was everything.” —M.J.

Photo: © Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

In a TV interview, she recalled her accidental debut: “I wanted to be a dancer. I never knew I was a singer until I made a bet with some girlfriends. They made me a bet and we signed for an audition at the Apollo Theater, and I was the one who was chosen, and I went on to dance. When I got on the stage, I lost my nerves when I saw all the people. The man said, “When you’re out here, do something.” My mother had a record of Miss Connee Boswell, and I tried to sing “Object of My Affection” like her, and I won first prize.”

Photo: Yale Joel/Time Life Pictures

“It was the beginning of what’s happened later on to Elvis Presley and the Beatles as it is today and the Rolling Stones. It was phenomenal. The biggest fan club in the world was outside the Paramount Theater, people waiting for hours and hours in the street just to have a glimpse of Sinatra. In those days, it was so inhuman for the artists to do seven shows a day, that’s how popular Sinatra became. I was pretty frightened because Perry Como [chose me as] a summer replacement. I had a million-selling record at the beginning of my career, but I still had a lot to learn. So I was pretty frightened, and so I went and took a chance and met Sinatra backstage and he was nice enough to have me up to his dressing room, and he said, “What’s the matter kid?” I said, “Well, I’m very nervous performing.” And he gave me great advice. He said, “Don’t worry about that. The public senses if you’re nervous. They’ll even support you even more, and you’ll find out it’s one of the best things that could ever happen.” And sure enough, it really relaxed me for the rest of my life. From that day on, we became great friends.” —Tony Bennett

Photo: Ike Vern/Time & Life Pictures

“There was no rock and roll when I was growing up. Late at night, I would find stations from Wheeling, West Virginia, or this country station coming out of Newark. I heard a Hank Williams song one day when I was 10 or 11, and I went out of my mind. He was so committed emotionally, physically, spiritually. It sounded like he would bite into his words at the end of a sentence and rip them off. Then I started listening to Jimmy Reed, and he was always inside the song, never trying. I wanted to groove like Jimmy Reed and communicate like Hank Williams.

I never knew I was a songwriter. I didn’t even know I was a singer. My parents just got me a guitar ’cause my uncle told them to get me one. There was a black superintendent of a tenement building on Crotona Avenue, his name was Willie Green; he played guitar, stuff like John Lee Hooker. I couldn’t wait to get out of school in junior high to pick up some of the riffs he knew. When I first got an audition at Laurie Records, at 17, Willie encouraged me. He said, “Be yourself. Do that song we usually do.” It was called “I Wanna Ride With You.”

For Dion and the Belmonts, I recruited the best street-corner singers in the Bronx that I knew—Carlo Mastrangelo and Freddie Milano and Angelo D’Aleo. I met Carlo up at Tally’s Pool Room on Crotona Avenue. He liked Duke Ellington, King Curtis. If you walked into the candy store on Mapes Avenue, Freddie Milano’d always be hugging the jukebox. He was really learning the harmonies. And Angelo D’Aleo, he studied opera and had perfect pitch. When I got them in my room in my parents’ apartment and we put “I Wonder Why” together, I was like on a heavenly merry-go-round. We needed a name, and all the insects were taken—you know, like the Crickets or whatever—and all the cars were taken—the Cadillacs, the El Dorados, the Impalas—and some of the birds were taken up—the Flamingos—so we started concentrating on streets. Back then, a rock-and-roll group needed a name that fit criteria in three areas: It had to be great for a bowling team, great for a gang, and great for a rock-and-roll group. We were gonna call ourselves Dion and the Crotonas, but Belmont had a nice ring.”

Miles Davis dropped out of Juilliard to play with Charlie Parker, paid his dues with a heroin habit, and emerged in the mid-1950s to form some of the greatest bands in jazz history. “We had Trane on sax, Philly Joe on drums, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and myself on trumpet. And faster than I could have imagined, the music that we were playing together was just unbelievable. It was so bad that it used to send chills through me at night, and it did the same thing to audiences, too. Man, the shit we were playing in a short time was scary, so scary that I used to pinch myself to see if I was really there.” —Miles Davis, from Miles: The Autobiography

Photo: © Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

As much as he was a singer, Pete Seeger was a musicologist who mined American music for songs with the power to change the world, and also an organizer who cajoled people to sing. He first found the song “We Will Overcome” among tobacco workers; changed Will to Shall; printed it in his New York newsletter, People’s Songs, in 1948; and in 1960, taught it at a workshop with civil-rights organizer Guy Carawan, who soon made it the song of SNCC, from whence it powered a movement. —J.H.

Everyone was under the spell of the clave, the mysteriously propulsive algorithmic arrangement of musical time and space that made Latin music an indelible sound of the New York street. People used to argue where exactly in Africa the clave came from, how old it was, or how it had traveled across the ocean in the slave ships to be perfected in the New World. But most agreed that it arrived in the Apple with Machito and his Afro-Cubans. —M.J.

The musical universe, says Mike Stoller, was contained in a white building on Broadway. When Jerry Leiber and I moved to New York in ’57, we’d had a number of hits already—“Hound Dog,” “Kansas City,” “Searchin’, ” and “Young Blood,” which was a million-seller single. We didn’t have an office at first, and in 1961 we moved to the Brill Building. It was between two eating establishments: the Turf, where the walls were covered with sheet music from the early ’40s and ’50s; on the other side was Jack Dempsey’s restaurant—the better-heeled and gamblers would have lunches there. The Turf was a hangout for a lot of musicians. If someone needed a bass player to do a demo, they could run over to the Turf and see who was there. Almost every floor of Brill was inhabited by music publishers, songwriters, bandleaders, talent agents. There were guys on the street who used the phone booth as an office. They’d give out the phone number, and would stand outside waiting for a phone call, trying to scare others away from using the phone. Next to us on the ninth floor was the office of Irving Caesar. Irving was in his late 60s; he wrote “Swanee” with George Gershwin, and “Tea for Two.” He’d be in early in the morning, and then we’d see him on his way to the track. Seemed many people in the music business were gamblers. Bobby Darin moved in when he moved out. Johnny Marx was in the building, who wrote “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” I guess every December he made enough to pay for a year’s rent. People would come up to the 11th floor and work their way down the staircase knocking on every door, trying to sell a song. The restrooms on the landings were used by a lot of R&B groups to rehearse, because the tile walls made a good echo. There were a lot of very good writers circulating who either had a publisher in the building or came from Don Kirshner’s office at 1650 Broadway, like Carole King and Gerry Goffin and Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. We often worked with Doc Pomus and his writing partner, Morty Shuman. Otis Blackwell, a wonderful writer who wrote “Don’t Be Cruel.” And of course Burt Bacharach, who was working with Bob Hilliard—in fact we made one of their first hits, “(Don’t Go) Please Stay” by the Drifters, which we produced. Barry and Cynthia, Carole and Gerry were also around. And of course Phil Spector, who had been a protégé of Jerry’s and mine. He was arrogant, and also talented. He put his arms around everything and claimed they were his. Unfortunately, he went on to take credit for everything Jerry and I did, including records we produced before he ever got to New York.

“I’d been on the road playing for acts—Vic Damone was the first, then the Ames Brothers. I’d hear some of these songs that were being submitted to the Ames Brothers, like the one song “You, you, you / I’m in love with you, you, you.” They had a big hit on that, and I thought this song was so absurdly simple, and maybe very easy to write, that I left to come back to New York to write songs. At the Brill Building, I became pretty good friends with Jerry Leiber. He and Mike Stoller were going to do a song of mine written with Bob Hilliard called “Mexican Divorce,” and they wanted background vocals. So we got this background group from New Jersey. That was an amazing group: Dionne Warwick; Dee Dee, her sister; Cissy Houston, Whitney’s mother; and Myrna Utley, who was a cousin. That was my introduction to Dionne. I saw Jerry in the studio and Mike in the control room when they did “On Broadway.” They had four or five guitars, percussion players, and a string section—all that going on! It was just amazing watching what they could get on tape, with that many people playing. Hal David, Hilliard, and I initially wrote some very bad songs. Our office window didn’t open, and Hal smoked constantly. There were a lot of turndowns in that period. There was a publisher named Goldie Goldmark, and after he’d had a chance to show a song Bob and I wrote, Goldie said, “No good. Nobody wants it.” Hilliard said, “Goldie, lie to me! Just tell me somebody likes it.”

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

as told to Joe Hagan

The Gaslight’s soundman Richard Alderson remembers the night Bob Dylan became Bob Dylan: “In the fall of ’62, I was living in Greenwich Village, and everybody knew Bob Dylan. I had done the sound system at the Village Gate and operated it. And when the new owners of the Gaslight, Sam Hood and his father, Clarence, took over, they hired me to put in a simple sound system.

Everybody said, “Well, Dylan’s written these great new songs, and he’s going to be performing them for the first time at this private, after-hours gig at the Gaslight. And you gotta come and bring your tape machine.” So I did. It was over two nights.

It was invitation only, and there were probably 25 people in the room. It started around midnight, after the Gaslight had closed for business. The first night was all sort of conventional, original Bob Dylan folk-music stuff. And the second night was the beginning of the Bob Dylan everybody knows. It was one of the first times he performed “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” You can hear his introduction to “No More Auction Block,” it’s the chords for “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which he hadn’t recorded yet.

I was sitting right in front of Dylan, stage right, his left. The stage was maybe two feet high. He wore the scruffy clothes that everybody associates with him. The weird jacket with the sheepskin collar and the funny little hat.

I used a portable Nagra, which was a tape machine that was made for early film work. Which is why all the songs begin and end oddly. The little five-inch reels would run out at odd times before the song ended, and I’d have to make changes.

I’ve never been in a situation where everyone was as rapt. It was like Jesus had come down and appeared in the flesh. And here was this guy, who was basically unknown outside of a small circle at that time. He was just beginning to break.

It was really an audition kind of a thing for him, where he was testing to see how people would react to this stuff that had never happened before. Dylan wanted to hear it, so he was more than willing to tape it. And there was never any talk about who the tapes belonged to—you know, at that time, they didn’t have great value.

I had a little one-room studio at Carnegie Hall with some big speakers that I’d built, and I brought him up and played Dylan the original ones. We got stoned together, and we were very relaxed. It was kind of like a serious moment, you know, like Picasso had just started to paint and he would show you his painting. It was like, What are you going to say?

I can remember he was happy with them. He wanted [Dylan manager] Albert Grossman to hear them, and that’s when I gave copies to Grossman—those are the copies people must have made bootlegs from. I remastered the Gaslight recordings in ’65. I just put the songs on tape that I thought were important—“Hard Rain,” “Don’t Think Twice,” “Hezekiah Jones,” “No More Auction Block,” “Rocks and Gravel,” “Barbara Allen,” and “Moonshiner.” When the tapes were finally released by Starbucks, they didn’t use “Hezekiah Jones” because Dylan uses the word nigger in it. They used “Rocks and Gravel” for a Jeep commercial and in HBO’s True Detective.”

The Fugs, led by Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg, made protest an ecstatic, sarcastic comedy (“Kill for Peace” was their hit), bridging the gap between Beats and hippies, creating a template later followed by Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. At the Bridge Theater, at 4 St. Marks Place, on August 7, 1965, a little more than a week after Lyndon Johnson sent 50,000 more troops to Vietnam, the Fugs held a “Night of Napalm.” After their set, in what they termed the “new Fug spaghetti death,” they pelted each other and their audience with spaghetti. “I spotted Andy Warhol in the front row,” Sanders once wrote. “It appeared that he was wearing a leather tie—then blap! I got him full face with a glop of spaghetti.” —J.H.

Not two years earlier, after a vicious bout of hepatitis, she’d been told she had only a few years to live and would never sing again. But on Sunday evening, April 23, 1961, Judy Garland, in good voice, moderate trim, and excellent spirits, performed for two hours at Carnegie Hall, the country’s most prestigious concert venue, bringing to bear on some two dozen songs all the entertainment know-how she’d acquired in 30 years of performing. A triumph, it was also, for her and for old-line pop entertainment, a last gasp (sometimes literally); three years later, the Beatles arrived on Ed Sullivan. Their sway over an audience would be different: diffuse and literally barricaded. Garland’s, as you can see in photos of the event—the men reaching up to grab her and she reaching down just as happily to be grabbed—was direct, seemingly personal, informed by her self-deprecating chatter about her hair and weight and also by their immense, inchoate gratitude. Which is why, despite astounding lung-splitters like “Swanee,” and “San Francisco” and “Chicago,” the concert’s highlights were the quiet ballads—“You’re Nearer,” “Do It Again”—in which her voice, unprotected by its brass armor, is a marvel of longing, phrasing, and making do with what you’ve got. “Do it again,” indeed; the live recording, which sometimes seems as if it’s half applause, has never been out of print. —Jesse Green

Photo: © Joshua Greene

“Paul and I would hold rehearsals in my basement, and we worked intensely to get a sound. Really serious rehearsals for hours, getting tighter and tighter in our blend. We were in junior high. I like to think of it as a New Yorker’s commercial instinct. There’s New York! We got a leg up. Because I was singing nicely at a young age and had this gift and it was noticeable, and because Paul came from a professional musician’s family, both of us already had one leg on the F train, going into Manhattan, going to the Brill Building, even though we were out in Queens, in Flushing, Main Street and Jewel Avenue. Soon we were copying the rock-and-roll records that we heard on the radio, emulating the sound. We loved Buddy Holly. [Sings] “All of my love, all of my kissing / You don’t know what you’ve been a-missing, oh boy!” That one, that was very up-tempo, very fast. [Sings] “Every day, it’s a-getting closer / Going faster than a roller coaster.” And we started writing our own rockabilly songs. We went to the Brill Building with our hearts in our throats. Paul and I and his guitar, we’d get on the train, and I would be absolutely fearful. This was kind of advanced, beyond me, and thank God I had my buddy, Paul Simon. The two of us could manage it, and I knew I had a singing voice in my throat. When you cling to those things—your pal, the guitar, the rehearsals that we’d worked on the songs, and this lucky gift I got from God, to be able to sing—you could make the leap from a middle-class Jewish kid in Queens to the Big Apple. And we would knock on the doors in the Brill Building—we were 14 years old, and I can see it now. They were invariably cigar-smoking businessmen that looked down on rock and roll as a dirty business. And with our hearts in our throats: “Anybody looking for material here?” “Whatcha got, kid?” And we would sing right on the threshold of the door—they wouldn’t even let us in. We’d sing a tune, they’d stop us on the third line. “No. What else you got?” —Art Garfunkel

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives

“Dave Van Ronk was loud and big and funny and laughed like a sailor. You could hear him a half-block away. He could also get angry and belligerent, but he had a huge generosity that just flew out of him. When I was working on my debut album, he told me that I didn’t give a fuck about folk music, which I thought was not really fair because I did. And I do. One of my first gigs was performing with Pete Seeger at Carnegie Hall. I knew his work, I knew a lot of folk music. I knew Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, I knew their work—that’s how I taught myself to play guitar. It’s the stuff I used to sing to the kids I babysat for. I loved it, but I wasn’t going to stay there forever. Van Ronk was particularly kind in the beginning, when I was 20, 21. By the time I was 25, I’d been around for five years and didn’t get a chance to make up with him. We weren’t close, but we were friendly. But I didn’t hold anything against him. It was at a birthday party for him, and I didn’t stay.” —Suzanne Vega

Photo: 1963 AP

At Shea in 1965, there were too many girls. “At Shea, we were in Jerry Schatzberg’s Bentley. [Ronette] Nedra’s then-boyfriend, Scott, looked like Paul McCartney, and Schatzberg looked like one of the Beatles—he had the long hair too—so when people saw us, they said, “There are the Ronettes! And there are two Beatles!” And they ran. We had to hurry up and close our doors. They started shaking the car back and forth. I said, “Jerry, we’re going to die here. We’re going to die!” Luckily, Bentleys are strong. I said, “Jerry, just put your foot on the gas and go!” But we couldn’t even move! Later, we took the Beatles up to Spanish Harlem, to Sherman’s BBQ. John Lennon had called me: “Ronnie, we’re prisoners here at the Plaza.” So I went down there and I snuck them out. At Sherman’s, no one paid them any attention! No one looked up from their plates! All people cared about was the jukebox and their ribs. They loved not being recognized. They loved not being screamed at.” —Ronnie Spector

“At my West Side Story audition, I sort of entertained him, because I sang “My Man’s Gone Now” from Porgy and Bess, and that, coming from my mouth and my vocal ability, was really pretty funny to him. When he did teach me the songs, he just made me do things and allowed me to realize there were things I could do I never dreamed I could. At that time, dancers really thought dancers dance and singers sing. I was brave to even go audition, because we just never thought we could get anything out of our throats—it all came through our feet. I was just hoping I wouldn’t throw up all over his piano! I remember putting my hands behind my back, I was shaking so much. You have to have people like Leonard Bernstein to teach you, to coach you, to give you that confidence. His adjectives were big and colorful. He did everything 200 percent, and you learn from that—you mimic that. It was like Technicolor. I mean, he was very sexy too. Please! He was handsome, and those eyes just sparkled—you’d do anything for him. Hit a high C—I would’ve done it. I’ll never forget when we were doing “Tonight.” Lenny was in the pit—he was conducting us, and he had more energy than all of us put together. He was pulling it out of us—and all of a sudden he disappeared. He was so energized that he fell through the chair! He just went straight through it.” —Chita Rivera

Preparing for her first Broadway star turn, Streisand explained to Jerome Weidman, the writer of I Can Get It for You Wholesale, why she’d changed her name. “I hapna love Brooklyn, but it’s like the name Barbara. Every day with the third “a” in the middle, you could go out of your mind. I mean, what are we here for? Every day the same thing? No change? No variety? Why get born? Every day the same thing, you might as well be dead. I’ve had 19 years of “Barbara” with three a’s and all my life born in Brooklyn. Enough is enough. Don’t you understand that?”

Photo: Harry Benson/2014 Getty Images

Richard Hell on why the genius of Lou Reed, John Cale, et al. has never been surpassed. In my opinion the Velvet Underground are the best rock-and-roll band in history. I’m still shocked and awed to rediscover this every time I listen to them. I can hardly contain myself. Just this moment, I played “Temptation Inside Your Heart” (recorded in 1968, unreleased until the VU compilation), for instance, and there are worlds in it. By many pop-music standards their recordings are ridiculous, but the recordings expose those standards as ignorant and inane.

I can’t deny it took me many ignorant and inane years to realize how good they are. I first heard their records when I was 17 or 18 and the band was actually playing in dark places in my neighborhood, but I never went to see them. They sounded to me like an incompetent Bob Dylan imitation. (This is the only thing that makes me think it might be worthwhile to live forever—the way one’s perceptions change across time. Then again, that can be exhausting, its own kind of monotony.) For a while back then—the late ’60s—I was hanging in the art world, where everybody seemed to dote on the Velvets, and I could only understand it as a kind of arty weak-mindedness of painters. Even when I started paying more attention to music a few years later and came to love them, they seemed like a sidebar. Now, after all these years, they’re the most dependable, inexhaustible music of all.

It almost makes me forgive Lou Reed for being such a shit. I never met the guy, but I’ve heard a lot of firsthand stories and read interviews. He wasn’t nice. He must have known how good he was. When I think about it, of course he did, and it was not only what made the music possible but what made him mean—he resented the various failures of proper respect for himself, because he knew he was right. Whatever. But it’s a similar thing that accounts for the supremacy of the band. The Velvet Underground is rock and roll without any niceties, without anything but rock and roll. There are no concessions to people’s needs for flattery and safety and polish. It is pure rock and roll and comes from absolute confidence. That doesn’t mean it’s ugly or cruel—there’s a lot of empathy and oceans of beauty in the Velvet Underground. It’s just that it operates on the certainty that rock and roll is enough; it’s everything.

I expect that a lot of how this came about for the band was that they were middle-class kids who had the values of avant-garde artists. Also that Lou Reed was psychotic. They didn’t aim to please. “Always leave them wanting less,” their mentor Andy Warhol advised. (How wack is that? That, on top of everything else they did right, they had Andy Warhol?) The band’s origins were in La Monte Young and John Cage (thanks largely to John Cale) and Ornette Coleman as much as in their love for Bo Diddley and Phil Spector and cheap rock and roll. (I have to name Sterling Morrison and Moe Tucker and Doug Yule, too. The group has never been surpassed.) Reed also brought a literary sophistication that was as disdainful of frills and concessions as his musical sensibility. His lyrics are the most genuinely poetic since Robert Johnson, and his delivery as seemingly throwaway as the band’s musical style feels. He does have that in common with Dylan: The vocals are so casual and sarcastic they hardly seem like singing at all. It’s nothing but rock and roll.

Photo: Nat Finkelstein

If you happen to find yourself on Soho’s western fringe, on King Street between Varick and Hudson, you may notice a building on the south side of the block, a former parking garage that these days houses a Verizon communications facility. Then again, the building might not catch your eye at all. A long, low-slung pile of drab grayish-brown brick, it has never looked like much—not even in 1977. Back then, 84 King Street was home to the greatest nightclub in New York, and in the world; it was the epicenter of disco, the incubator of house, the cauldron in which more or less all of the dance-music culture that has followed in the decades since was cooked up. Which is to say: It was the domain of DJ Larry Levan.

Impresario Michael Brody opened the Paradise Garage in 1977. Fun was the mission of the club—but Brody was serious about fun. The Garage cultivated an exclusive, largely gay clientele and served no alcohol or food; he installed a gargantuan, state-of-the-art sound system, with walloping subwoofers, and placed the DJ at the center of the action. The Garage was, in other words, the model for the megaclubs that have followed, laying emphasis on music and dancing.

In Levan, who began his decadelong Saturday-night run at the club in 1977, Brody found the right priest for his temple. Levan was wizardly and innovative. His epic DJ sets mixed disco and soul and rock; he experimented with synthesizers and drum machines, weaving the disparate music into an eclectic, beatific flow. A commenter on discomusic.com recalled the effect of Levan’s music. “I was a helpless puppet being wildly manipulated by a mad puppeteer,” he wrote. “I became one with the music and the experience, and I have never been the same since.” —J.R.

Photo: photo by ©Tina Paul 1987/©Tina Paul 1987

On how a Studio 54 doorman inadvertently helped write a disco smash. “Grace Jones expressed interest in having me and Bernard Edwards possibly write and produce her next album. Obviously we knew her music and we knew who she was, but we had never spoken to Grace Jones. On the phone she had this very bizarre vocal affectation; when you hear her speaking voice it’s so over-the-top. We just thought she was putting on this voice for us as part of her code message on how to get into Studio 54. So she says, “Tell them you’re personal friends of Miss Grace Jones” [in a faux-Austrian accent]. So we knock on the door and say [in the same accent], “We are personal friends of Meees Graaaysss Jones,” and the guy slams the door in our faces and tells us to fuck off. And we say, “No no no no. Seriously, seriously, seriously,” and we try and get it better. “Weeee’re personal friends of Meeeesss Graaaaysss Jones.” We sounded like Bela Lugosi. He slammed the door in our faces again and told us to fuck off. So we realized that wasn’t going to work. We bought a couple of bottles of Champagne, which we used to call rock-and-roll mouthwash in those days—Dom Pérignon—because we were doing okay, and we just started jamming on a groove. And we were like, “Aww, fuck off!” ’cuz that’s what the guy told us to do. “Fuck Studio 54!” It was sounding great. And then Bernard, in his infinite wisdom, said, “My man, you know this shit is happenin’, right?” And I was like, “How are we gonna get ‘fuck off’ on the radio? No way.” And he’s like, “No, man, I’m telling you, this is really good.” So we changed it to “Freak Off.” And me being true to my hippie roots, the acid head in me, came back, said [in a California-dude affect], “You know, like, how about, man, we call it ‘Freak Out’?” Bernard was like, “What does that mean?” And I was like, “You know, when you drop a tab of acid, man, and things go bad.” And he’s like, “What the fuck?” So immediately I pulled myself together and was like, “No, man, you know when you go to a club and you’re freakin’ out on the dance floor.” And Bernard said something incredible, he said, “Plus my kids are doing that new dance called the ‘Freak.’ ” And I went, “That new dance called the ‘Freak’? Right, Goddamn!” So we made it about being in Studio 54 dancing this new dance. Later, I practically lived in Studio 54.”

Photo: Michael Norcia/© Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

“We used to rehearse in this bicycle store up on the West Side, Columbus and 82nd. The guy used to rent bicycles in the summer, and then we would go in and rehearse during the wintertime. There was a welfare hotel across the street, and we played their holiday show, and that was probably our first performance. So much of the Dolls, it’s like a crazy mishmash. Somebody would have a loft, and we would end up with 50 people there and the police coming. We were kind of pioneers in a sense. We used to have to go into bars or places and convince people that they should have a band. Once we started playing there, it opened it up to a lot of other bands. That’s what happened at the Mercer Arts Center. Suicide started playing there. Great band. The Modern Lovers as well. We were very much comrades. Nobody really articulated it, but we were trying to get a scene going. The East Village at that time was a hotbed of avant-garde everything. The high heels were easy. There was a shoemaker on Second Avenue who used to take the heel off and put in a steel shank so it was kind of indestructible. You could play basketball in them. We would put lipstick on when we were onstage. We didn’t think of it as drag. We were just trying to be what we thought somebody in a great rock band should look like.

At the time, so much of the music that was popular at the Fillmore was kind of like shoegazing, you know? There were so many bands that didn’t do anything, they just stood there and played. We wanted to put the Little Richard jolt back into rock and roll. It wasn’t like we had any kind of ultimate goal or anything. It’s funny, you read a snapshot of history of the Dolls, and it’ll say, “Oh, the Dolls played, but they failed to reach a mass appeal.” This “failed to reach a mass appeal” is the most ridiculous thing in the world. Like that’s the end-all of everything. Which is what the current culture is predicated on. Financial success defines artistic success. But I think the success of an artist is to be inspirational.” —David Johansen

Photo: P. Felix/2006 Getty Images

“There was a bar Patti was playing in, I remember seeing them, and it was basically poetry. Her songwriting was just being developed. I was asked to produce the record that became Horses. They had a lot of really good energy, and it was a family; they were really close-knit. They’d come up through the trenches. And Patti was boss and inspiring. The only challenge I had was getting a really good basic track that was in tune, because the instruments were out of tune. They had these instruments that they treasured, and I came along and said, “You can’t play them anymore. We’re spending more time tuning the damn thing in between takes than we are getting to a good take.” So we called up and got a bunch of new instruments, and that caused a ruckus. All of a sudden they didn’t know how to relate to the new instruments that they got. I mean, Lenny [Kaye] knew what the problem was, but it upset the apple cart a bit, and that’s why it took a little longer. I remember getting Ivan [Král] a Les Paul, and he was happy with it once he got his head around it. It worked. Then I suggested that Patti improvise poetry on top of her lines; she just did that, she just naturally took it over. And when it came to mixing the track, she sat down and did what she felt was right for the two voices. She understood the point between dichotomy and schizophrenia. We were downstairs at Electric Ladyland, downstairs in the dungeon. The thing that kept us laughing, there was some guy during a performance of Patti and the band when they were on tour who came up and in a hallowed voice asked Patti, “Who does your hair?” Nobody did Patti’s hair!” —Velvet Undergrounder John Cale

Photo: Allan Tannenbaum/Allan Tannenbaum

“I’d look at various DJs of that time era, and the way that they were transitioning, I found them to be bumpy. It wasn’t smooth. It wasn’t clean. What was going on inside my head was, How am I going to control this drum solo and make it seamless? Eventually I figured out that in order to control the audio source, the vinyl, a lot of these DJs were using the tone arm. So now I started studying turntables, how they work. I came up with what I call torque theory: When you turn the turntable on, I would lightly rest my hand on the platter to see if the motor had enough muscle to be able to handle me moving my wrist back and forth over the vinyl. Many turntables failed. But there was a little-known company called Technics, and they had this ugly turntable in the window called SL-120, and they were $75 apiece.

Then I had to figure out, “How can I hear the signal of the source in my ear before you can hear it?” So that’s when I created this peek-a-boo system. The peek-a-boo system consisted of a single-pole double-throw switch in a center position, to split the two signals. So when you click it to the left, I could hear the left turntable. Two clicks to the right, I could hear the right turntable. So now I was able to take these songs that had these teeny-tiny drum solos and just make them seamless. I would mark the record with a grease pencil or a crayon, where the break lived, and all the intersecting points. So when I wanted to repeat a break all I had to do is watch how many times the intersecting line passed the tone arm. If it passed four times until it went to the wack part, all I had to do was just rewind it backward and count.

The crowning achievement for me was that I had to do what all DJs wouldn’t do—physically put my hand on the record. My theory was, everything should be controlled via the vinyl, the fingertips. DJs used to treat vinyl like children! They would wipe the record down, and they would very carefully slide it back in the jacket. Me? I was just pulling the record out of the jacket and making it dirty! It had crayon marks all over it! But that was a way that I could execute what was going on inside my head. I came up with a science, you know, with the touch of my hand on a record. I came up with a science that almost the whole world does.”

Photo: David Corio

Hip-hop’s origin story in 1970s New York City is a loop of fable, fact, and circumstance (see Robert Moses’s divisive Cross Bronx Expressway). But Jamaican transplant Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell has been championed, and has championed himself, as the key originator, though Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation demur. The West Bronx high-rise 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, where Herc (short for “Hercules,” a nod to his burly frame) threw parties in the small first-floor rec room, has been dubbed hip-hop’s birthplace. But let’s be honest, no one person could’ve birthed hip-hop’s crazy quilt of styles and rituals. What Herc did was throw the best parties—the loudest, sweatiest, most undeniable. His jams (in parks and elsewhere, featuring his oversize “Herculord” sound system and rapper Coke La Rock) were a refuge from street gangs and silk-shirt disco, but they were historic for how Herc dug into the percussive, fiercely funky “breaks” often found on records by James Brown and more exotic obscurities (English rockers Babe Ruth, the Incredible Bongo Band). He’d shift from break to break in different songs, a routine he called the “Merry-Go-Round,” pushing B-boys into a dancing frenzy and laying hip-hop’s rhythmic groundwork. The rest, like so much, remains history’s ongoing mystery. —Charles Aaron

Talking Heads’ Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth on the Ramones and Talking Heads. Our first show was opening for the Ramones at CBGB in the fall of 1974. We had been going to CBGB from pretty much the first night we moved to New York. The first weekend I went, Patti Smith performed. I went back the following weekend, and the Ramones played. The Ramones were in their formative stages, and they would stop and argue with each other in the middle of a song. Johnny would say, “Okay, stop, stop. Something’s not right. Let’s play ‘I Don’t Wanna Go Down to the Basement.’ ” And Dee Dee would say, “No, Johnny! I don’t wanna play ‘I Don’t Wanna Go Down to the Basement’!” To my way of thinking, it was really advanced artistically, even though a lot of people said that they were moronic.

Tina: “The one who always took authority was Johnny, because Johnny had gone to military school, and he had, let us say, a very stern father. Totally conservative. Republican …”

Chris: “I would say reactionary. But anyway, when it came time for us to make our debut, our audition at CBGB, I spoke to Hilly Kristal about it: ‘Hilly, we have a band …’ He recognized me from being a regular patron there, and I said, ‘We have a band, and I think we’re ready to do a show here.’ And he said, ‘Well, I could put you on with the Ramones.’ Someone asked Johnny, ‘Is it okay if the Talking Heads open for you?” and Johnny said, “Oh yeah, they’re going to suck, so it’s no problem. They can open for us.’”

Tina: “A few years later, in the spring of ’77, we went on tour to Europe with them.”

Chris: “It wasn’t a regular rock-and-roll tour bus, with bunks and everything; it was just like a tourist bus, with seats. So the Ramones would sit in their assigned seats, and we would sit pretty much wherever we wanted, and we would change seats from time to time, which really upset Johnny because he liked everybody to be in the same seat each day. And one of the famous episodes was the first show we went to: We went straight from the plane to the sound check in Zurich, Switzerland, and it was a nice theater and it had a restaurant connected to it, and we were allowed to have dinner at the restaurant. So we went down there and they started us off with a beautiful salad, nice, leafy green lettuce, and Johnny said, ‘What the fuck is this?!’” [Laughs]

Tina: “He wanted iceberg lettuce. He would hate kale. He would hate everything like that.”

Photo: Roberta Bayley

“John lived right across the hall from me. I used to hear him play through the wall. As a matter of fact, I heard him writing “Imagine” through the wall. Mmmm, yes I did. Whoever sits down and plays the piano in that room, it usually comes trailing through the wall. I was in the studio with him on a couple of occasions; it was like a special thing that I didn’t take for granted. I was so nervous. I was going, I’m going to sing with John Lennon, whoo! And that’s what it was like being this close to him, hearing him write songs through the wall. In the case of “Imagine,” I know that was him, because, like yourself, I know that song now. But I didn’t know it when I heard it. I couldn’t hear, “Imagine there’s no heaven …” I couldn’t understand the words that well. But I could make out the melody and the little chords. And when I heard the full song, I was just completely overwhelmed.” —Roberta Flack

Photo: 2005 Getty Images

“I was in fifth grade when I first heard Billy Joel, and I think the first Billy Joel record I heard was The Stranger. I guess that was about ’77. When I discovered The Stranger, I think that was the record that got me to finally listen to something more than the Beatles. I definitely identified with him a lot as a kid, because I was a piano-playing kid, and he was from the area, and I knew some of the places, or I’d heard of some of the places, that he was singing about, especially on that record. But a lot of his records were filled with story-songs, songs that were telling little stories, and that’s a way that I ended up writing, more often than not. I think Billy Joel’s written a lot of songs that have ended up essentially being new classics, and I think he’s someone that rock critics have always looked down on as not authentic in some way, but his songs have outlasted many other people’s songs.” —Adam Schlesinger of Fountains of Wayne

Photo: Don Huntstein/Courtesy of Sony Music Archives

At the Bottom Line in 1974, the stakes were high, as his introduction to “Kitty’s Back” reveals: “Before I came in tonight, somebody sent me this box, this long box, and I opened it up and in there was this knife—remember that, boys? It was covered with blood. There was a little letter explaining that this was an approximation of … of how my blood would look on that knife if I wasn’t good tonight, because … Kitty’s back!”

“Klaus Nomi, as far as we were concerned, was a bigger rock star than Mick Jagger, because he seemed so completely otherworldly. What I loved so much about the music and the culture back then is that on first glance, none of it made any sense. And it seemed like part of the criteria by which it was judged was, how effectively did it challenge the viewer or the listener? There was nothing about Klaus Nomi—or Sid Vicious, for that matter—that was accommodating. You felt like it was your duty to try and understand what he was doing. He was this otherworldly, Nosferatu-style benign operatic vampire. And what I was incredibly grateful for is I lived in Darien, Connecticut, in this really conservative, dry, anodyne suburb, but we were 40 minutes away from Manhattan, which at the time was this amazing, dysfunctional, crumbling, artistic place. So much of the otherworldly culture coming out of Manhattan seduced me, because it was just the antithesis of what I was experiencing on a day-to-day basis in the suburbs. There was nothing [laughs] suburban or American or quotidian about Klaus Nomi!” —Moby

Photo: Francois LE DIASCORN/Francois LE DIASCORN/RAPHO

“I bleached my hair and I started getting a lot of street noise about it. And we had been trying to think of a good name that would be commercial and easy to understand, and one day I was walking along Houston Street, Chris Stein was living on First Avenue, and somebody yelled, “Blondie!” out the window, and I said, “Oh! Gee, that’s an easy name to remember.”

Then Chris and I got a loft at 266 Bowery, right down the street from CBGB. It was a pretty strange building. It had once been a sweatshop, maybe a doll factory. On the ground floor, the street floor, was a liquor store, where all the Bowery bums would get their Night Train. We thought it was haunted.

Record labels weren’t running out to sign the next hot babe. They were looking for, you know, cute guys. It made me feel like they were really stupid and missing the point. It probably made me feel more aggressive. And sometimes it probably made me more frustrated. I think it was a time of aggression, in a way. People were struggling so much at that point. And it was sort of like staring out into the void. As much as you wanted to think that you were going to be a huge rock star, nobody was really; it wasn’t really making a dent in anyone’s income. It was strictly determination and that kind of aggression.” —Debbie Harry

“Do the Right Thing takes place on the hottest day of the summer. And one thing about New York City is that there’s always one song that becomes the song of the summer—coming out of people’s cars, it’s coming out of people’s windows, it’s coming out the boom box, back then. So I wanted to have a song like that, an anthem. And automatically I thought of Public Enemy. There was no one else making that type of music, their lyrical content, the militancy. Here’s the thing that a lot of people don’t know—“Fight the Power” was not the first song that was submitted to me. No. The first song was a good song, but it wasn’t really what I wanted. By that time, we had a cut, so I showed him the film. And Chuck got it. He sat in the front and I was sitting in the back while he watched it, and he loved it. They were hyped. I mean, they had never seen a film like this before, dealing with issues like that before. And let’s remember, 1989, New York City was a very racially polarized city. You got Koch, you got Howard Beach. Things were tense. And they understood exactly the tone, the message, and what this film was saying. And once I showed him the film, they murdered it. Chuck D and the Bomb Squad came back with “Fight the Power.”

They came back with this gem, and I lost my mind. [Laughs] I was jumping up and down, like I had stuck my finger in an electric socket. Because I knew that this song would propel the film.” —Spike Lee

Photo: Lisa Haun

By 1986, one of New York City’s most epochal structures was a grimy relic. Built for the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens’s Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, the Unisphere had fallen victim to budget cuts—its geyser fountains, which once gave the illusion that the 900,000-pound, 12-story-high, stainless-steel model of the Earth was floating above the ground, were dry. Speckled by litter and graffiti, it wasn’t even a storied skateboarding spot yet. Once symbolizing the city’s, and America’s, expansive ingenuity at the height of the Space Age, the Unisphere instead spotlighted our petty dysfunction.

But when Def Jam Recordings co-founder Rick Rubin envisioned the gatefold art of the Beastie Boys’ ’86 debut album, Licensed to Ill, he had only one setting in mind. “Rick and Russell [Simmons, Rubin’s Def Jam partner] had this idea of the Beasties as a ‘Let’s take over the world’ kind of thing,” explains Sunny Bak, who took the iconic photo of the Boys posing in front of the silver orb.

A New Yorker who attended the ’64 World’s Fair as a child, Bak remembered the “Globitron” (as it was later known) in all its original splendor. She was also a part of the Beasties’ circle—they frequented her studio on 18th and Broadway, which was used as the site of the “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)” video. “I practically had to move because of the sour smell; I couldn’t get the whipped cream out of my carpet,” she now says wryly. In case you’re wondering, Bak contends that she never visualized fans rolling joints on her handiwork. There’s been a lot of chatter over the years that the Beasties were “typical New York kids.” Maybe in some idealized sense, but it’s more that they were gifted boho interlocutors who were adept at playing a variety of kids, real or imagined, while their music cannily exploited the myth of the city as a free-floating cultural playground. —C.A.

In a mid-aughts interview, the late Mark Kamins, the Danceteria DJ who helped produce her first single, remembered her priorities: “We had no money and we were sleeping on egg crates. She wasn’t a homemaker. I bought some lingerie for her one night, and she wasn’t interested. To Madonna, a boyfriend was secondary. She knew how to use her sexuality to manipulate men, everyone from promotion guys to radio programmers.”

Thurston Moore on discovering a downtown poetry. “I remember living in Connecticut and seeking out the documents and buying records in places like the Sears record department. Rock Scene was the most important magazine, because it would have all the heavyweights in there, but they were also covering what was going on in the margins of the New York scene. That was really exciting, these little clubs in New York City, because the people just looked fabulous and the music sounded intriguing. Seeing images of Patti Smith standing on the subway platform—all of a sudden it was cool to be in the city. It was this postapocalyptic landscape for artists. I ran to it. I wanted to see Patti Smith.

As soon as I could I sought out Max’s Kansas City. I drove along Park Avenue and yelled out the window, “Where’s Max’s?” The first thing I saw was the Cramps, and they were just playing old sixties garage-rock covers, these spindly American lost gems. And we were just like, “What is this?! This is not … this really is not Pink Floyd, at all.” And then Suicide came out. Alan Vega would wrap his microphone cord around audience members’ necks and scream in their faces. Everybody was barricading themselves behind the tables at Max’s so this singer would not attack them. It was that violent! And weird! I just knew at that point that I was in New York City. It was the sound of downtown New York. Everything about it aesthetically was what I wanted. I wanted that in my life.

I started playing with these guys and moved in with them on South Street in ’76. Kim [Gordon] was in New York to do art, and she also wanted to play guitar, even though she wasn’t trained. Neither was I. It was about creating your own language on the instrument that had all this tradition to it, without denying the tradition. But the technique of the tradition wasn’t necessary for you to create. That was so liberating and exciting and wonderful and beautiful. There was no ambition about it, except to maybe get a gig in a gallery or a loft. Punk rock was an artist’s music, even though it was expressing this reclamation of rock and roll.”

Photo: Ebet Roberts

On confronting one of his idols. “I was very influenced by Miles Davis, but we didn’t really get along. I met him in 1981; Herbie Hancock introduced me to him in Boston. When he saw me, I had a derby on and a polyester gray suit, and he said, “So, you the police, ah?” I didn’t know what he was saying, so I said, “I’m the police? What do you mean by I’m the police?” He said, “You comin’ out here to clean this shit up.” So, you know, it was just like that. I was about the integrity of jazz, and not just making it another type of backbeat pop music. That’s what I grew up playing, so I knew there was a difference. I felt jazz music needed someone to champion it and say, hey, this music is viable and is important too. I always loved his playing—I idolized him—but from a philosophical standpoint, I clashed not just with him but with many people in the field. The guys in my band dared me to jump on the stage with him. All three of them put up a sum of money, and they said they thought I was afraid of him, so after the funds accrued, I said, okay, I’m going to go jump out of the audience. They were playing this blues called “C.C. Rider.” He cut the band off after a while. He requested that I get off the stage—but I had done enough to win the bet.”

Photo: Deborah Feingold/© Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

There never was a New York hip-hop season quite like the autumn of 1994, when 22-year-old Bed-Stuy native Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G., released his debut album. Biggie, who signed with Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs and later joined Bad Boy Records, had been popping up in guest spots. The 1993 single “Party and Bullshit” confirmed the suspicion that the guy was an outrageous talent, a rapper with mesmerizing flow and a devastating gallows-humor wit. He was also, emphatically, a local hero. The songs on Ready to Die gave gangsta rap a New York spin. Like Mickey Spillane, he was a virtuoso teller of hard-boiled street tales, and he was a thugged-out Woody Allen, a classic New York neurotic, stressed by the squad car on the corner, by other hustlers eyeing his loot, by the “everyday struggle.” Ready to Die wasn’t just a personal triumph, it was a municipal one: a New York reclamation of rap, whose center of gravity had shifted to Los Angeles. Of course, the East Coast–West Coast feud was far more serious than anyone believed; soon, it would claim the lives of both Tupac Shakur and Biggie. But for a glorious long moment, New York hip-hop felt reinvigorated, even utopian. Puff’s own debut record, No Way Out, released in the wake of Wallace’s murder, was also unmistakably a New York record: With the album’s shiny surfaces and endless boasts about cash flow, conspicuous consumption, and high-end brands, Puff launched hip-hop into the bling era. —J.R.

In 1999, the Bronx diva talked about her earliest musical education: “I remember being 2 years old and being put on the table and—in Spanish they say menéalo; it means ‘Shake it, shake it.’ I think I was probably dancing out of the womb.”

Photo: Cliff Lipson/2003 Wireimage.com

On a summer day in the early ’90s, Marc Anthony, a 21-year-old singer from East Harlem, found himself in a predicament familiar to a native New Yorker: stuck in a bumper-to-bumper crosstown traffic jam. Anthony’s friend, who was driving the car, dropped a cassette into the tape deck, cuing up “Hasta Que Te Conocí,” a swooning sentimental torch ballad by the Mexican singer Juan Gabriel. “You want to talk epiphany?” Anthony says, recalling the moment. “It was beyond an epiphany. I felt like I was levitating.” Anthony made his friend pull over the car so he could call his manager. “I need to record ‘Hasta Que Te Conocí,’ ” Anthony said. “Well, Juan Gabriel already recorded it,” the manager replied. “Maybe do a salsa version?” Two weeks later, Anthony was in a studio, giving salsa a next-generation makeover, supercharging its bustling rhythms and brass fanfares with injections of modern club music and R&B. —J.R.

Photo: Arnaldo Magnani

On the darkness behind the ecstasy smiles. “In 1990, a 19-year-old kid would go out to a rave or a club and take one or two hits of ecstasy and have an amazing time. By 1993, a 19-year-old kid would go to a rave or a club and take Special K and acid and crystal meth and ecstasy, all in the course of one night. Every now and then I would run into Michael Alig on the street and I would see the consequences of drug use. Because in 1990, Michael Alig had been this light and bubbly and happy-go-lucky club kid. And before he ended up going to prison, he became this vector, just trailing darkness around him.”

Photo: David Corio/Getty

Jay-Z asked me to work on a song with him. He was retiring, and he was making what he thought was his last album. He wanted one song from each of his favorite producers and asked if I would do it. That was my first hip-hop song since the early days, and that was “99 Problems.” It was really fun. He was incredibly inspiring as a lyricist. We worked on a lot of ideas, and then he honed in on the track that felt most exciting to him. Actually, Chris Rock had the idea for the chorus. It’s based on an Ice-T song called “99 Problems,” and he said, “Ice-T has this song, and maybe there’s a way to flip it around and do a new version of that.” And I told Jay-Z the idea and he liked it. The Ice-T song is about “got 99 problems and a bitch ain’t one,” and then it’s a list of him talking about his girls and what a great pimp he is. And our idea was to use that same hook concept, and instead of it being about the girls that are not his problem, instead of being a bragging song, it’s more about the problems. Like this is about the other side of that story. —Rick Rubin

Photo: Arnaldo Magnani

It is hard to imagine at this late date, but there was a time when hip-hop and R&B were like oil and water. “You singers are spineless / As you sing your senseless songs to the mindless / Your general subject, love, is minimal / It’s sex for profit,” ranted Public Enemy’s Chuck D. in 1988—and the disdain was returned by singers who were wont to dismiss hip-hop as a sub-musical nuisance, when they weren’t suing rappers for copyright infringement. All that changed with the arrival of Mary J. Blige. On her 1992 debut album, What’s the 411?, audiences met a new kind of R&B star. Blige was an around-the-way diva—a Bronx-born, Yonkers-bred homegirl who had a firm sense of the musical past but was firmly of the hip-hop generation. She had a big, gusty voice, with a soul woman’s feel for drama—and melodrama. But the attitude was straight hip-hop. What’s the 411? had something for the old-timers—a lush, lovely cover of Chaka Khan’s “Sweet Thing”—but it held a novel kind of wistfulness, too—hip-hop now had its own brand of nostalgia. —J.R.

Photo: Des Willie/1996 Des Willie