As told to Jennifer Vineyard

My dad is a massive music fan, so even just growing up in the house, he was buying new cool music, up through when I was born. So I was very familiar with the Ramones, Run DMC, Blondie—core New York music. My parents would often play the Ramones song “We’re a Happy Family,” so I remember when I was 9 or 10, learning the lyrics and trying to understand. At first I didn’t grasp the irony of the song, but then I got it. When you’re a little kid, you just remember the “We’re a happy family / me, mom, and daddy” part, and then when you’re older, you get how sarcastic it is. By the time I got to high school, I had some older friends who were really obsessed with hip-hop, De La Soul, Tribe Called Quest. There’s something about Midnight Marauders; it feels like a late night in the city album. The Low End Theory has its own distinct sound, and they complement each other. I like a lot of the stuff from that era, but Tribe was the one I felt closest to.

Once I got to college, I started seeing a lot more shows. I remember seeing the Roots a lot, like at SummerStage. Seeing Dizzee Rascal’s first show in America. He performed on a flatbed truck. I saw the Streets’ first New York show.

I didn’t become obsessed with music because I saw live shows that blew me away. I became obsessed with music because I was exploring my parents’ record collection, and spending hours in friends’ bedrooms listening to music. I like the imaginary space of the album. More than anything, I feel very at ease with the internet for music, because that’s an imaginary space, not a physical space. I remember when people first started having Napster and playing MP3s, and in some ways, I was like, This is perfect. This is what we always wanted. Just to be able to play each other music, hang out in somebody’s bedroom, just, like, chill. So now the fact that music does exist in a nonphysical space, I love it. That’s not to say I don’t appreciate a beautiful venue or a historic recording studio, but that’s very secondary to me. I like the ideas of music and the concepts. I’m glad the tail end of my childhood overlapped with the internet era of music, because I can still feel nostalgic for the early parts of the internet era of music. It’s not such a clean break. So yes, the nonphysical space.

My first summer back home in New Jersey after freshman year, my friends and I started making this movie called Vampire Weekend. Not because I love vampires, but because I love that kind of weirdo stuff. Never finished it. A few years later, I found the footage, and that was around the time I started to get an idea to start a band. So it basically all just kind of naïve college days. The band, we were all friends, and we knew we were all kind of into music. We worked on other things together before, this rap group for a while. There was a class a bunch of us were in together called Music, Race, and Nation. I wrote “Oxford Comma” on a piano at my parents’ house in New Jersey, and I started to get this idea: It’d be cool to start like a preppy band. That’s kind of all the original idea was. And the first practice, we played “Walcott,” “Oxford Comma,” some other songs that I had written, and some covers. Pretty soon after that we had “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa,” and I felt like after we had “Walcott,” “Oxford Comma,” “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa,” then it was like, Okay, this actually feels like something.

I’d seen there was this Facebook group at Columbia called Students for the Preservation of the Oxford Comma, and that was the first time I’d heard of an Oxford comma. And that appealed to me in a lot of ways, because it has Oxford in it, and I like anything Oxford: Oxford button-downs, Oxford University, all that stuff. But then the fact that it’s a comma, the combination of something like really regal and at the same time, absurd. I remember sitting at my parents’ piano, and that was the first thing that came to my mind: “Who gives a fuck about an Oxford comma?” That’s the first line. I never would have guessed that nine years later, I would almost daily have kids on Twitter making Oxford comma jokes. “Oh, by the way Ezra, I DO give a fuck about an Oxford comma!” I must get that four or five times a week. So I never would have guessed that it would continue. I guess it’s an eternal debate. “Oxford Comma” was the first one where the ideas kind of coalesced. “Walcott” at its heart is just a straightforward rock song, whereas “Oxford Comma” had a bit of a groove, and that to me was the real beginning of Vampire Weekend, at least in the way I thought of it. So for that one to be the one that resonated with people was meaningful. We played Glastonbury after “Oxford Comma” came out, and in the Anglosphere, it’s our only Top-40 single. We got this bottom of the barrel Top-40 single, and suddenly, we’re playing this huge crowd and people are reacting, singing it! And something clicked for me. In some ways, “Oxford Comma” seems like one of the more esoteric songs, because it’s an incredibly obscure or nerdy or silly reference. Which made me realize, you can’t think that way. If something’s funny or unique, don’t worry about trying to generalize it. Maybe you’ll be playing it in a field to 10,000 people, which is just fun.

Being at Columbia, you’re a little bit isolated. You get a sense that cool things are happening in Brooklyn, but you don’t feel very much a part of it. As we started to play, even the idea of forming a band then was like a little bit funny. Which is why we naturally gravitated toward the great African electric guitar tradition as opposed to the U.K./American guitar tradition, because it felt a lot fresher. When we first started playing, people would say, “That’s not the way to rock.” “Oh, no, we can’t do a disco beat.” It wasn’t an amazing time for bands. So that gave us a slightly more unique way to approach being a band. And I knew people like Dave Longstreth [of Dirty Projectors], who I thought was doing really cool stuff, within the kind of big concept of a band. But I didn’t really feel a sense of community with other people in New York.

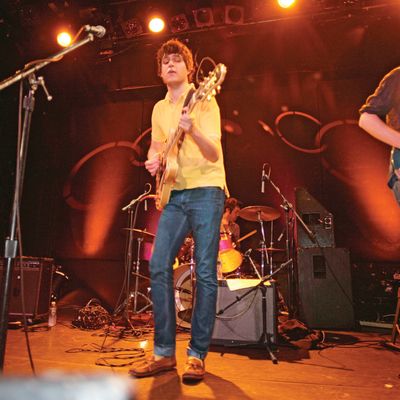

We played at Glasslands [in South Williamsburg], and that was a big show. That was the first time that we had sold out a venue we had heard of, and that also happened to be the first time a major newspaper wrote about us—the New York Times. Of course, any time you get written about in the early days is exciting, but the first time you get written about in the New York Times, you get emails like, “My dad was having breakfast and he pulled out this picture of you.” It was a really hot and sweaty show. A lot of the early shows—it might sound absurd for me to say—had a punk-rock flavor, with people really dancing, moshing almost, and just being really sweaty and crazy. I remember it being really hot and high energy. That was definitely a pivotal show. I remember Wes came on stage and sang Fleetwood Mac’s “Everywhere,” and that was kind of just for fun. We were just doing our thing. The more shows we play, the tighter we get. Sometimes the best shows come out of a comfort of being effortless.

Around the time we were wrapping our tour around Contra, we had sold out three nights at Radio City. There’s a grandeur about that venue, and there’s something about doing a stand in New York City. That felt like a big deal to me, a real homecoming. We had finally, truly established ourselves. Something about that felt like a special moment.

*This is an expanded version of an article that appeared in the March 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.