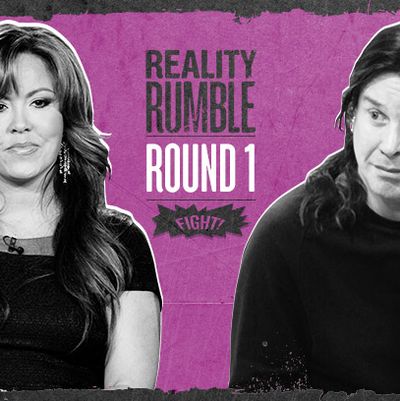

Vulture is holding the ultimate Reality Rumble to determine the greatest season of the greatest reality-TV shows, from The Real World on. Each day, a different writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until Vulture’s Margaret Lyons judges the finals on March 25. As round one continues, Anne Helen Petersen pits So You Think You Can Dance’s third season (featuring Danny and Sabra) against the Patient Zero of celebreality, the first season of The Osbournes.

The reality-TV epoch has been marked by a handful of truly original concepts followed by countless variations on the form. Usually these copies, with their minor tweaks on their predecessors’ formulas, feel stale and uninspired. But on those rare occasions they discover something new in the format, and emerge as something fresh and exciting. Today’s combatants both could have been forgettable cash-ins — So You Think You Can Dance inspired by the era’s biggest reality hit; The Osbournes by the family killing on an episode of MTV Cribs. But with American Idol producers Nigel Lythgoe and Simon Fuller behind So You Think You Can Dance, it immediately distinguished itself from Idol by its incisive and knowledgeable judges. And who wanted to know what Ozzy Osborne was doing on a day-to-day basis? Turns out, everyone. The first execution of a genre we’ve come to know as “celebreality,” The Osbournes grafted the tropes of the classic sitcom (nuclear family, bumbling dad, controlling mother) onto the most un-classical of subjects, with electric results.

Parts of So You Think You Can Dance (now approaching its 12th season) do resemble the Idol format: Americans who believe they have talent audition; a few dozen are selected, and those dozen are whittled down to a single winner, through the process of judge critique and audience votes. But SYTYCD doesn’t waste its time exposing less talented hopefuls to national humiliation; in fact, one of the hallmarks of SYTYCD is its refusal to waste time. There’s no ten-minute cutaway to a contestant’s melodramatic background, no stunt casting. Every contestant has legitimate, breathtaking talent, every judge has an actual critique, and any drama that does take place behind the scenes is masterfully sublimated in the actual dances. (See, for example, the “man dance-off” between Broadway hoofer Neil Haskell and classical ballet dancer Danny Tidwell at the end of season three, our pick for SYTYCD’s best season; the number transforms the tension and different styles of the two remaining male dancers into a riff on two princes dancing for the throne.)

SYTYCD wants to force its contestants outside of their dance comfort zone and, in the process, expose Americans to the expansive marvel that is “dance.” If Idol is a soap opera, and Dancing With the Stars a weird form of dance-themed celebrity rehab, then SYTYCD is a service program — it really is all about the dance. Like Top Chef, SYTYCD trades on the notion that people don’t need reality foolery when you’ve got the spectacle of talent. I’d watch the clips of the dances on repeat for days, and so would millions of you, if the YouTube numbers are to be believed.

As for The Osbournes, I wish we could hop in our mental time machines and go back to March 2002 to witness just how fresh, how different, this show felt. Sure, MTV had The Real World and Road Rules, but Ozzy was a true depraved rock star — with his bat-eating, ants-snorting mythology, who would have ever pictured him having a loving family, let alone struggling to figure out a remote control? And there he was, shuffling around his house, being put in his place by his wife, Sharon, and befuddled by his children, Kelly and Jack. The SNL-skit-like concept of “Ozzy as Ward Cleaver” was the hook, but what kept you watching was the fact that this loud, un-house-trained family had such an authentic bond — more so than the cardboard smiles and back pats found in Leave It to Beaver. The Osbournes launched a still-cresting wave of voyeuristic celebrity-life shows (Newlyweds: Nick & Jessica began the following year), but none have ever felt quite so much like you were getting a true vision of what the central has-beens acted like when the cameras were off. Whether or not producers were off-camera, dreaming up fights and dog-poop placement for the Osbournes, it never felt staged.

In judging between the best seasons of both shows, let’s begin with the characters. Like other “democratic” reality competitions, SYTYCD always starts with a veritable spoonful from the American melting pot — virtually every ethnicity and class group is represented. Or at least that’s how they’re framed: Each contestant is saddled with adjectives that stick with them from the duration of their time on the show (season three breakdancer Dominic, for example, was always referred to in terms of being from “the streets”), if only to show just how much they’ve transformed, both in terms of dance ability and personal identity. And this transformation provides the show’s emotional and artistic wallop: Season three was the show’s high point partly because of its handful of revelatory numbers from blossoming dancers.

My favorites included Sara, the tomboy from Colorado who’d never worn heels but went on to perform an exquisite tango, and Dominic, the arrogant B-Boy who looked so at home during the touchy-feely “contemporary” (which appears to be shorthand for lots of scarves and bare feet and rolling on the ground). My favorite was the Russian ballroom dancer Pasha, who not only mastered West Coast Swing and hip-hop but made the best, most bashful faces of any contestant in the history of the show. He’s the nerdy immigrant (“I’m trying to be cooler!”), which is part of the reason that his mannequin hip-hop dance, when he plays a nerdy guy lusting after a gorgeous mannequin that comes to life, has become a series classic.

Everyone else in America loved Sabra, the plucky amateur who first started dancing just four years before, and Danny, the ballet dancer whose brother, Travis, had been runner-up in season two. Whereas Sabra was eager and smiley, endlessly malleable and appreciative of the judge’s remarks, Danny behaved like he was hot shit. That behavior would get most dancers voted off, but Danny’s talent was impossible to ignore: He was smug, he didn’t partner well, but he could dance.

The Osbournes is another beast entirely: a ‘50s sitcom through a glass darkly, a point that its cheery credits, complete with a faux–Pat Boone cover of Black Sabbath’s “Crazy Train,” makes clear. Each of the characters plays out familial tropes, but they do so in weirdly compelling ways. I want to think that Kelly and Jack are spoiled brats, for example, and the bulk of their actions would seem to communicate as much, but there’s something ineffably vulnerable about each: You think their parents’ fame will make them cocky and/or sophisticated, but outside of the home, they’re both so tentative and nervous. With their big mops of hair and eager eyes, they don’t inspire pity so much as endless curiosity.

Mom Sharon is a firecracker: She says things like “I hate cooking … Martha Stewart can lick my scrotum,” and while you expect her to be a ball-busting mom, she is endlessly supportive of her kids. And as for Ozzy, I can think of no reality character so confusingly hypnotic: I find his voice oddly soothing, and the tension between the moments when he declares “I’m the Prince of Fucking Darkness” and stares, transfixed, at the History Channel, are the very foundation of the show. Is he high? Addled from previous drug use? Or just a blundering Dad?

But you know what makes good characters great? Their interactions with other good characters. In The Osbournes, we see plenty of Kelly wrestling with Jack, and Sharon dressing Ozzy up in ridiculous “metal” outfits and nuzzling him before he goes on air, but for me, the best interactions were always between Ozzy and Kelly. When Kelly barges into the living room complaining that Sharon’s set up an appointment with “the vagina doctor,” Ozzy’s reaction is an ellipsis of concern, bafflement, and fear. When he counsels Kelly that “All you gotta say is ’Fuck off’ when the vagina doctor calls!” it seems clear that Ozzy loves Kelly deeply — and her unfettered willingness to talk to her dad about it (and first thing when she walks in the door!) underlines just how much she trusts Ozzy. It’s a weird, twisted moment, at once hilarious and tender, which is precisely what made that first season such a national phenomenon, and SYTYCD, comparatively, just a fun thing you watched on summer nights.

On SYTYCD, all of our narrative comes from the dancers’ interactions with either the partners, judges, or choreographers. The partners themselves are generally edited to seem super flirtatious — an easy way to telegraph heterosexuality, dancers’ actual inclinations be damned — and respectful of each other’s talent. When beloved Sabra and still-sorta-asshole Danny were asked to say something about the other dancer on the season finale, they both blathered on about what an honor it was just to be on the stage with such a talented dancer, which is the sort of banal crap that always makes me want to fast forward. When judge/choreographer Mia Michaels, still mourning the death of her father, crafted a dance in memory of her relationship with him, it was performed with much earnestness by Neil and Lacey — but it was also just a bit too on the nose to truly touch me: authentic emotion writ (too) large.

But the interactions between the clearly dominant Danny and judges — that’s another story entirely. From the beginning, Danny was constructed as arrogant, but not with the “boy from the streets” rhetoric that surrounded breakdancer Dominic. (This despite the fact that Danny began his dancing career in an afterschool program for at-risk youth.) Even if you knew nothing about dance, you knew that Danny was something extraordinary: His dancing was so electric, so graceful, that whenever he was onstage, it’s as if his partner melted away.

And the judges took Danny to task, week after week. In SYTYCD, the judging panel is always expanding and contracting to allow for guest choreographers, but the season three near constants were Mia Michaels (the modern dancer in touch with her feelings), Adam Shankman (best known for being one of Paula Abdul’s backup dancers; directing A Walk to Remember AND Hairspray; and continually marveling at how hot and talented the dancers were), Mary Murphy (former ballroom dancer; all smiles, “you’re amazings” and happy claps), and Nigel, who functions as the SYTYCD equivalent of Simon Cowell, only with an artistic eye instead of an economic one. Together, they form a perfect mélange of genuine joy in the pleasures of dance and honest, instructive criticism.

But their treatment of Danny helped make it into the narrative of season: He was clearly the front-runner, but would he learn to play by the SYTYCD rules? Guest judge and choreographer Shane Sparks declared that he “stood there like he was God’s gift to the world,” while Shankman told him that he danced “like you think you’ve already won the competition.” And Nigel’s advice was somewhat uncharacteristically shrewd: Danny lacked that “little bit of magic,” i.e., charisma, that “makes people want to pick up the phone.”

The perfect, type-A, exacting ballerina … so good that America hated him! But as a New York Times article entitled “So He Knows He Can Dance” pointed out, Danny was didn’t actually need changing — “and both his unflinching poise and his chiseled, determined jaw seem to indicate that he knows it.”

But after being forced to “dance for his life” twice within the first three weeks of the main competition, Danny tried to loosen up — clumsily at first, but then, near the final episodes, he would send sassy messages to Nigel during the practice sessions, winking, literally and figuratively, at the judges’ instructions. But it always felt forced and flat in a way that The Osbournes always, at least in that first season, so deftly avoided. I always felt like Danny was hiding a (totally legit) frustration that he had to play cute to a contest that he would’ve won, no question, on skill.

Reality competition finals should offer the most legible of narratives: good vs. evil, innocent vs. scheming or, in the case of season three of SYTYCD, classically trained (Danny) vs. novice (Sabra). It’s a great New American Dream story, and it’s utterly unsurprising that Sabra won — a testament to how much America believes that “natural” talent can triumph over discipline. As critic Sarah Blackwood once pointed out in Salon, the show doesn’t award America’s best dancer, but its favorite one.

So You Think You Can Dance, especially season three and Sabra’s win, not only suggested that talent was malleable and taste could be transformed, but also that heterosexuality was winning, traditional training isn’t necessarily necessary, and niceness trumps all else. That’s a boring story, and part of the reason that Sabra has faded from memory even as specific performances — Mia’s Dad Dance, The Hummingbird Dance — have not.

Season three was a forum for some truly moving dance moments, yet it failed to make good on its potential to tell a different sort of reality story. Just years before, the phenomenon that was The Osbournes had proven that America was willing, with the slightest amount of pushing, to embrace the imperfect, but SYTYCD’s extension of that principle (yay amateur Sabra; boo professional Danny) didn’t feel progressive or risky, it just felt dull.

The Osbournes may seem a little creaky now, but don’t blame the show: Its willingness to wed the uncanny with the bright, blazing lights of the lit reality home, its stunning ability to undercut and complicate our understanding of the lived experience of celebrity and stereotypes — it’s not wrong to call it revolutionary, at least in terms of television genre. Without The Osbournes, there’d be no Kardashians, no Duck Dynasty. Its tropes, now tired, were once so fresh as to become a phenomenon. I’ll never tire of watching clips from SYTYCD season two, but I’ll never forget The Osbournes.

Winner: The Osbournes, season one

Anne Helen Petersen teaches media studies at Whitman College, writes Scandals of Classic Hollywood, and spends time on Twitter.