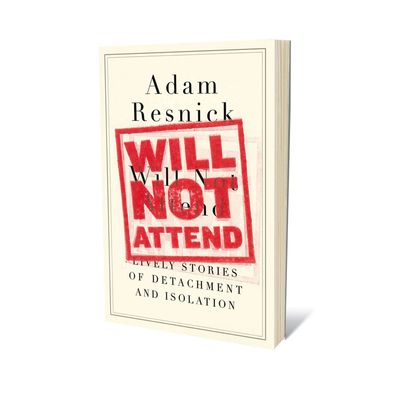

ItÔÇÖs pretty much a well-known fact that there is nothing┬ámore difficult┬áthan being funny. ItÔÇÖs much harder to make someone laugh than it is to operate on their brain or send them into space. But Adam Resnick has never shied away from hard work ÔÇö just people. In his new nonfiction book, Will Not Attend:┬áLively Stories of Detachment and Isolation,┬áthe esteemed former Late Night With David Letterman writer and Chris Elliott cohort (Get a Life and Cabin Boy) manages to crack you up on one page and have you in tears the next. And not because itÔÇÖs sad, either ÔÇö because┬áyouÔÇÖre chuckling so strenuously. I first met Adam in 1986, when I was interning at┬áLate Night┬áduring his long and influential stint there; he and I forged a deep bond over being anxious and┬áconstantly sleepy that continues to give us common ground all these years later. We caught up recently and discussed various neuroses, the Letterman days, and why his ideal place to live would be Overland Park, Kansas.

Before we begin the interview, check out AdamÔÇÖs recent appearance on┬áLate Show With David Letterman, in part so you can see what he looks like.

You talk a lot about being crazy. How has that served you?

Well, when IÔÇÖm talking about myself, ÔÇ£crazyÔÇØ is just a┬áromanticized┬áword for┬áneurotic.┬áTo say┬áthat IÔÇÖm neurotic is a bit misleading because it conjures up the image of a person with all types of worries and phobias. While I am a worrier, I donÔÇÖt have classic neurotic fears. For example, IÔÇÖm not a hypochondriac. I donÔÇÖt obsess about death. I┬áhave no patience for people like that. You know in Annie Hall, thereÔÇÖs the two lobster scenes ÔÇö one┬áwith Diane Keaton, who gets Woody AllenÔÇÖs character and finds his fear of escaped lobsters amusing, and the later scene with the woman who doesnÔÇÖt? And she says something like, ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs the big deal? YouÔÇÖre a┬ágrown man. TheyÔÇÖre just lobsters.ÔÇØ IÔÇÖm that lady. I mean, jeez, first of all, how did the f***ing lobsters get out in the first place? The guy wouldÔÇÖve had to physically remove them from the box and place them around the kitchen. And then what? Make some kind of a scene, so his┬ágirlfriend┬áruns in and saves him? Because heÔÇÖs afraid of lobsters? DonÔÇÖt get me wrong, itÔÇÖs a pretty good movie, but keep me away from┬áanything┬áresembling that guy.┬áSo, to the┬áextent┬áthat I overanalyze┬áand get annoyed by things like that might indicate a basic all-over-the-map craziness. No need to put a fancy name to it.

So what are you afraid of?

Human incompetence and laziness. That will ultimately be the downfall of the planet. You heard it here first.

How did you feel writing about people who are alive, particularly family members, who will presumably be reading your book? If you donÔÇÖt mind me saying, you didnÔÇÖt pull any punches.

ThatÔÇÖs how it read to you? IÔÇÖve been bullshitting myself for over a year that I was using a ÔÇ£light gloveÔÇØ┬áapproach. I thought I┬áwas┬ápulling punches. I was constantly toning┬áthings down┬áand editing out the really bad stuff. And sometimes I used┬ápseudonyms and changed certain details to further disguise people. All I can say is, no one comes off worse than myself. Give me that much, at least.

Though your book is extremely funny, itÔÇÖs also quite poignant. Were you conscious of that? Was it a relief to not have to be ha-ha funny every page?

The stories had to be funny to a large extent,┬áotherwise they┬áwould have been too difficult to write, or to even think about. I┬áwouldnÔÇÖt┬ábe able to pull off the Tobias Wolff version. But yeah, as you so beautifully put it ÔÇö I wasnÔÇÖt always going for┬áÔÇ£ha-ha funny.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs a lot of personal stuff in there I have yet to find humor in. Besides, IÔÇÖve never been much of a joke man. Or a song-and-dance man, for that matter. Wait ÔÇö was that a joke?

Did you find writing the book easier or more difficult than screenwriting?

Writing is always a bitch, I think. But IÔÇÖd say I found writing the book way more┬áenjoyable and┬ásatisfying┬áthan screenwriting. For better or worse, itÔÇÖs completely mine. It doesnÔÇÖt have to be turned into anything. Very few meetings are┬árequired. The erosion┬áprocess that typically begins once your writing takes the trip towards being┬áÔÇ£producedÔÇØ doesnÔÇÖt happen. Of course, if the bookÔÇÖs shitty, youÔÇÖre fucked.

People always want to know what it was like to work at Letterman. Tell me the best and worst things about it.

It was all great. IÔÇÖve said this before ÔÇö they was the happiest years of my life. Anything I did after Dave ÔÇö real show-business stuff ÔÇö was never as fun, and in fact, could be pretty awful. As far as bad memories, the only thing I can think of is the fucking birdseed. [Beat] Just go out on that.

Who do you think was the best intern you ever met at Letterman, and if it was me, why? Just kidding.

Well, IÔÇÖd like to think I was the best intern. I did it for about nine years. Back then, at least a third of the U.S. Department of Labor was in DaveÔÇÖs pocket, so no one came sniffing around. But I can still feel those bags of birdseed on my shoulder. His secretary sent me out every day for six of them, rain or shine. Fifty pounds each. At first I thought it was nice that he liked birds so much, but then I found out it was just to lure them towards the porch so he could throw hammers at them.┬á┬áSo ÔǪ other than myself, you were the best intern, Julie. You were bright and, I seem to recall, very clean-looking.

I donÔÇÖt know if you remember, but back in the day, you and I used to talk about what our perfect jobs would be. Mine was working for Woody Allen from┬á10 a.m. to 2 p.m., with two hours for lunch (this was pre-controversial Woody). Tell me what your perfect job would be now ÔÇö or better yet, your perfect life.

Well, back then, I was already working my fantasy job ÔÇö writing for Late Night. Now, I usually daydream about being a different person. Someone whoÔÇÖs wired to be calm and optimistic, and lives in a nice town like Overland Park, Kansas ÔÇö a beautiful place, by the way ÔÇö and I have no creative urges. IÔÇÖm not overly ambitious. I have no envy, jealousy, or sense of competition. Everything is steady and uncomplicated and my family is the only thing thatÔÇÖs important to me. Essentially, weÔÇÖre talking about a brain transplant.

Who is in your mind as your audience when you write? Is it your wife? Your daughter? Your dog?

IÔÇÖve talked about this before; the main person in my head when I write is Dave Letterman. After all these years, I still want to please him more than anyone. Sometimes, though, when IÔÇÖm just doing a money job and IÔÇÖm not creatively enthused, IÔÇÖm thinking, Please, Dave, forgive me. Like IÔÇÖm sinning, you know? Sort of a ÔÇ£Dave as GodÔÇØ type deal. Just good mental hygiene, is all.

Tell me what question I neglected to ask you?

I canÔÇÖt think of anything. Probably something about Bridgegate.

Adam Resnick will discuss Will Not Attend with Bob Odenkirk at Book Court in Brooklyn tomorrow at 1 p.m.