Editor’s note: This essay first appeared on May 1, 2014, after the death of the longtime Mad magazine editor Al Feldstein. To mark the news of of Mad’s forthcoming closure, we’re republishing it today.

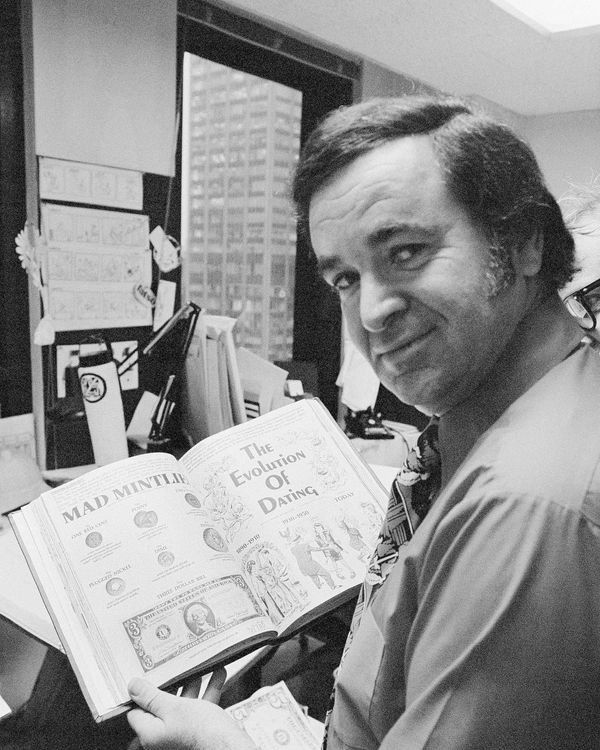

When people think of Mad magazine, they recall the familiar features: Al Jaffee’s Fold-ins, “Spy vs. Spy,” the floppy-footed guys drawn by Don Martin, Alfred E. Neuman on the cover. Some talk about William Gaines, the eccentric owner-founder-publisher who relentlessly kept overhead low and spirits high. Comic-book enthusiasts talk about Harvey Kurtzman, the magazine’s original editor, who set its boundaries wide open and established its DNA. But only the true fans think of Al Feldstein — who died on Tuesday at 88, and edited Mad from 1956 to 1985 — and he is, arguably, the man who made it the incredibly influential publication it was.

When Feldstein took over Mad from Kurtzman in 1956, it had published all of 28 issues, and just a year earlier had shifted from being a comic book to a standard-size magazine with a glossy cover. (In the business, the new format was called a “slick.”) Its form was in flux, but Kurtzman had figured a template: movie parodies, social commentary, ad parodies, and single-page multi-panel jokes, all for 25 cents (“Cheap”). The tone was arch, but not louche like Playboy’s or uptown like The New Yorker’s; it was down-and-dirty, more Lower East Side than midtown. The offices were on Lafayette Street, amid the sweatshops and light industry of downtown, and Feldstein himself was from Flatbush. In fact, the Jewishness of Mad’s humor cannot be overstated: It was, for many people outside New York, the first place they ever heard words like knish and shnook. The very first issue, in 1952, included a crime story titled “Ganefs!” The editors’ favorite words seemed to be “Blecch!” and “Yeccch!”

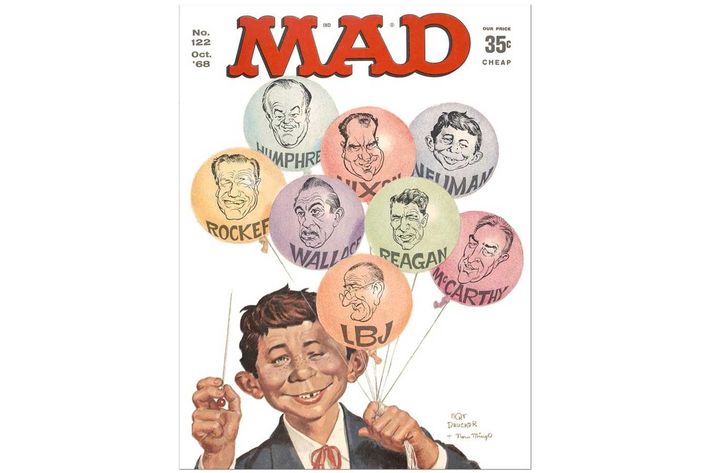

Most of all, though, it was about irreverence. Where other magazines would be uneasy about taking a straight-on shot at the Catholic Church, Mad — and I remember every amazingly well-drawn pane of this story, as if I’d seen it yesterday — showed a portly priest walking a visitor through his church, showing off the wildly ornate and expensive fittings, and then cheerfully opening the front door to reveal that the opulence was surrounded by a desperately poor slum. Every president caught flak from Mad, no two more than Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Corporations got it worst of all, at least when they deserved it: The earliest hard knock on tobacco executives that I ever saw was in Mad. Many companies were horrified at the parodies of their ads that Mad ran; eventually they came around, realizing that their having their images parodically savaged made them seem a lot hipper than they were, and they stopped threatening lawsuits. So did songwriters, and in fact, a suit by Irving Berlin made it all the way to the federal Second Circuit in 1964, where a judge backed up Mad’s right to spoof his lyrics. Turns out that it’s legal to turn “A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody” into “Louella Schwartz Describes Her Malady.”

Some say that Feldstein took the sharpest edges off Kurtzman’s magazine, and maybe he did make it somewhat more mainstream — if such a furshlugginer creature could ever have been “mainstream” in the 1950s and 1960s — but he emphatically did not dumb it down. One glance at a Jack Davis and Arnie Kogen version of M*A*S*H, for example (it’s called M*U*S*H), reveals a superb piece of drawing that completely takes the piss out of this great but sanctimonious sitcom. On the first page, Father Mulcahy reads from Scripture:

“And They said, ‘Let this Show be Different from other Wartime SitComs! Let there be Brisk, Witty Dialogue! But, along with the Comedy, let us show the Stark Reality of War! Let our Show have Integrity!’ And it did! And the Public saw that it was Good! And on the Seventh Day, the Creators rested in the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel!”

Feldstein must have been good at managing upwards, because he did all this with Gaines, a vigorously political Republican-libertarian, in the owner’s chair. Clearly, though, he was also a master at keeping his team of weirdo artists and writers working productively. There is no magazine — not Playboy, not The New Yorker, not Reader’s Digest — that had such a consistently loyal talent pool over the decades. (Al Jaffee is still there, in fact, after nearly 60 years on the job.) Feldstein bought stuff from unknown cartoonists when they walked in off the street — and in the case of Sergio Aragónes, when the unknown in question didn’t speak any English. Longtime contributor Dick DeBartolo tells the story of sending in his first work when he was in high school: A thick envelope came back a few days later, and he didn’t even open it for awhile, figuring he’d been rejected. Once he did, he found a wad of cardboard with a note from Feldstein’s deputy Nick Meglin, saying “Ha ha, thought we rejected your script, but we bought it! Stapled to this cardboard is your check! Please call us about writing more stuff for us!” He did, and still does.

Feldstein also was smart enough to run with an image Kurtzman had dug up and re-drawn on an inside page of the magazine: a dopey-looking, gap-toothed kid they called Alfred E. Neuman. In the fall of 1956, Feldstein put him on the cover as a write-in candidate for president, and he’s been there pretty much ever since. According to The Nation, he eventually won the White House.

It’s a little too much to say that Feldstein’s Mad magazine created the 1960s, but it’s not a totally outlandish idea, either. Its general editorial ethos of “trust nobody who’s trying to sell you something, including us” was, to young boomers and Gen-Xers, irresistible, and we all know that the stuff you read when you’re 10 years old sticks with you in a way that even teenage experiences can’t: You absorb it into your psychic makeup. Future beatniks gravitated to, and had their thought processes formed, by Mad; so did future hippies and Yippies. Future Reaganites, too, for that matter, though they probably missed the point. We would not have had Spy magazine without Mad, nor The Daily Show, nor Colbert, nor CollegeHumor.com, nor Gawker. (Nor, probably, the sound and ethos of the blog you’re reading now.)

Mad itself, now published six times a year, is a hit-or-miss affair these days, largely because it got online late and weakly. Often the magazine seems like it’s straining under its own legacy, seeming to believe it needs to deploy its old wisecracking-in-the-CCNY-cafeteria tone where the sad-funny, more delicate voice of The Onion might get the job done better. (The Onion, in fact, is probably Mad’s truest heir, and has tacitly acknowledged its debt.) Besides, a deliberately cheap-looking print magazine probably can’t be the cultural force it once was. At its peak, in 1973, Mad topped 2 million copies per issue, and the business of the slicks is gone for good.

But every year or so, Mad’s editors produce a cover that has some of the snap and spark of its best days, and you see it on a newsstand somewhere, and it’s good enough that you want to tell your friends. You could tweet it — but then you’d be the sucker, standing there with your stupid expensive phone! Handing over your privacy to a bunch of millionaire California dorks in hoodies? You’re exactly the shmuck that Mad would make fun of, aren’t you? Yeah, they got you again! Yecch.