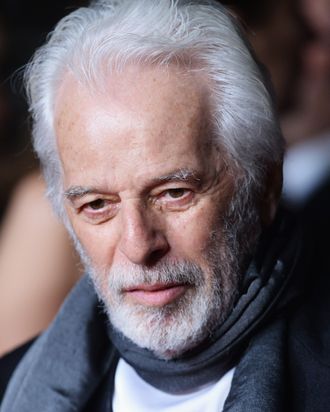

Art and history unfold at their own pace for French-Chilean artist Alejandro Jodorowsky. The 85-year-old filmmaker and comic-book writer is most well known for seminal midnight movies like The Holy Mountain (1973), a consciousness-raising exploitation film that both Marilyn Manson and Kanye West swear by. But Jodorowsky’s now more active than ever. He’s currently working on comic-book sequels to both El Topo (1970) and The Incal (1981–1989), respectively a midnight movie and the comic book series that The Fifth Element mercilessly ripped off. And after 23 years of waiting, Jodorowsky finally wrote and directed The Dance of Reality, his first film since little-seen 1990 fantasy The Rainbow Thief.

In The Dance of Reality, Jodorowsky collects and mythologizes autobiographical stories about his traumatic childhood in Tocopilla, Chile. The film is a family affair: one son, Brontis, plays Jodorowsky’s father, while the other, Adan, composed the film’s soundtrack. Re-creating his own past helps Jodorowsky to keep it from stagnating in his mind as a staid reality. Like much of his art, his film encourages viewers to make up their own mind as to what is real and what is tall-tale exaggeration. Vulture talked to Jodorowsky about his new film’s approach to history, his hatred for movie theaters that serve food, and his love for Drive director Nicolas Winding Refn.

Your father is played in the film by your real-life son, Brontis. Brontis was also in El Topo. I know you felt guilty about his involvement in that earlier film. After asking him to bury his own teddy bear, you apologized to him, and made him dig up his teddy bear, saying, “Now you can be a child.” Do you think that what you asked of Brontis was … too much to ask of a child?

Yes, yes! A person is not the same in his life at all times. Your consciousness is developing all the time. When I started making El Topo, I was one person. When I finished that picture, I was another person. And when I made El Topo, I was just asking [Brontis] to kill some rabbits. “Just!” Because at the time, I said to myself, “We should give everything to art.” So when I finished the picture, I became more human, and asked forgiveness from my child. I’d never kill an animal; I became conscious. If you don’t make errors, how can you be conscious?

Does the process of making your art — whether it’s your comics, your films, your writing on tarology, or your practice of healing and psychomagic — require you to abandon your conscience? Do you have to completely give yourself over to your art, to the demands of what the work needs?

I realize that I’m not just a person who thinks, but a person who feels. I have desires, sexual desires and creative desires. These have nothing to do with thinking. My body has needs, to be healthy, to have good air, to have good water, good space … my body wants things, normal things. Sexually, I am getting old. My desire is changing. I don’t want to just love my family; I want to love all of humanity. I said proudly, “I’m Jewish,” but the Palestinians are people, too. I want to know why we’re fighting. It’s a war of idiots against idiots. And I see big corporations destroying the planet to get more money. It’s not normal!

Also, every day, I think I’ll die. What does it mean to die? What does it mean to despair about this? Many people think about God when they think about death. But what is God?? The Arabs have a God, the Jews have another, and the Catholics have another! And they’re all fighting to maintain that they worship the one real God. Idiots! Religion is idiocy. I’m a conscious person, but I was also born in that world. I made errors, but step by step, I’m trying to amend those errors. [El Topo] was very intellectual, and [Dance of Reality] is very emotional.

In your book [Psychomagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy], you talk about how people have “programmings,” or ideas about how they’ll behave based on the established behavior of their parents, or siblings. I wanted to apply that to your films. So Brontis is playing your father in Dance of Reality. And there are aspects of your father in the character you play in El Topo, specifically the way you discipline and train Brontis to harden his heart. How have these films helped you to break out of your own programming?

A picture is for the public, but it’s also for the people who do the picture. Psychomagic puts everything in your genealogical tree in its place. So when Brontis plays my father, he’ll understand why I made him play myself [in El Topo] while I was playing my father. Then he could understand. Myself, seeing my son as my father … my son, who used to be a little boy, he became my equal. Father and son are now on the same level, not the son under the father.

The use of gore in both El Topo and Holy Mountain is striking. Is it fair to say that you tried to shock viewers so that they were more receptive to the way you talk about how reality, as we experience it, is a series of veils that we have to pierce to get to the truth?

The violence in El Topo is humorous. Because when you see violence in American industrial pictures, or in Chinese pictures, there’s joy in that violence. They like that violence! Me, when I show violence, I am critiquing violence. It’s different. I make the violence non-real. I’m encouraging people to have feelings about what they’re seeing, but I also want them to know that it’s art, that it’s not real. I don’t hypnotize you. The commercial hypnotizes you, and makes you into a violent person. You start to want to kick somebody, to be Superman, something like that, no?

But in the moment of filming scenes of violence and nudity, did you have that kind of alienating — in a positive way! — kind of effect in mind? These are fairly extreme images: Were you anticipating the way viewers would absorb these images?

Yes. I did not anticipate how they’d be received, but I was hoping that they’d be received freely, without my influence. While watching a scene of torture [in Dance of Reality,] a viewer can laugh, or be horrified. Someone else could find this scene’s concept of universal suffering to be beautiful. Another might be able to identify specifically with my father, who is being tortured in the scene. I make the scene, but I leave you to have your own feelings. I don’t direct the way you should react. I don’t want to do that. I am not a Hitchcock. I am not a Spielberg. I am not a degenerate.

You’ve have to contend with the similarly dogmatic vision of film censors, people that have a checklist of offending material that they look out for, regardless of context. And their ruling helps to determine how many people get to see your films. When you make a movie, do you think about how your work will be evaluated by censors, or was that not even a consideration for you when you made Dance of Reality?

In the history of art, there’s never been an artist that’s been completely accepted. Mondrian, Shakespeare, Cervantes … every one of them had admirers and had enemies. An artist needs to have the courage to do what he thinks he needs to do. Industrial artists think of what they can do with what they have before they start doing. That’s not me. I think maybe [censors] will love, maybe they’ll hate my work. For me, that’s not a problem. Nothing is a problem for me. When I made El Topo, I was ahead of my time. I had to wait 23 years before I could make Dance of Reality. I am passive. If I can’t make the picture my way, okay, I’ll do something else. And when I didn’t make Dune, I thought, Okay, maybe this will be impossible to do, but I’ll try to do it. [Dune] changed my life. My soul grew; I didn’t fail by not doing it.

Moebius, your former collaborator, once said that your art tends to “undermine the resistances of reality.” I’ve also read critics praise Moebius by describing his Blueberry Western comics as a transition between his work as Moebius and his work as Jean Giraud. Do you think an artist’s work, especially one like Moebius’s, progresses? That is, are there stages to an artist’s body of work?

He started as Jean Giraud, and he finished as Moebius. When he made Western comics, he had a mentor called Jije [the pen name of Belgian comics artist Joseph Gillain]. And he made almost ten books imitating Jije. But when he changed the instrument he used to imitate Jije, he discovered a new way to do things, and he became himself.

You’ve said in the past that, when someone goes outside of their normal role in society, they discovered new aspects of themselves.

We have various actions, and we’re afraid to do anything else because we’re afraid to do something new. If you do something different, you discover things about yourself that you didn’t otherwise know. That is how I invented Psychomagic. The main principle is to do something that you’d otherwise never do.

You’ve incorporated elements from your unrealized Dune adaptation into your comic books. I’ve read that you’re doing that with Sons of El Topo. How far along are you with that project?

I have the script in four volumes.

Do you have an artist attached yet?

Yes, [José] Ladrönn. He’s also working on After the Incal. He’s better than Moebius, you’ll see. As for Dune: [record producer] Allen Klein asked me to adapt The Story of O. I really wanted to get out of my business agreement with Klein. And [film producer] Michel Seydoux showed Holy Mountain in Paris, and loved it. And he said to me, “I want to produce for you a big picture. What do you want to do?” I say, “Dune.” Because a friend of mine tells me that it’s a very good book, though I didn’t know the book! He tells me it’s a science-fiction book about ecology. I say “Fantastic!” When I started to write my film’s script, I read the book. And I thought What have I done? Adapting Dune is impossible! After 100 pages, you understand nothing!

So I thought, This is so literary … I need to make something more optical. So I made a book called The Optical Book of Dune. But when I didn’t make Dune, I thought I’d take everything of mine and use it for comics: The Incal, Metabarons, Technopriests … I don’t know, 40 volumes of comics.

[Drive director] Nicolas Winding Refn dedicated Only God Forgives to you.

He is a friend of mine!

Only God Forgives also seems influenced by your work, particularly its view of subjective, semi-dream-like violence.

Yes! As for myself, I met Refn when I was in a bookstore and saw a poster for Bronson. I said, “What is Bronson?” I was astonished! It was a really artistic movie. Then, L’Etrange Festival, a film festival in Paris, asked me to introduce a film I liked. I say, “Valhalla Rising!” I chose to show that one because the friend that sent me a copy of Bronson told me that the same filmmaker made a Viking picture. I thought Wow, how can I see that? So I said “I want to introduce Valhalla Rising!” They called Refn and said, “Jodorowsky wants to introduce your picture? Do you want that?” “Not only do I want that, I want to know him! When I was 15 years old, I saw his pictures, and he changed my life!”

I offered to read the tarot for him, and from then on, he had me read his tarot every time he made a new movie. I can’t see the future, but we can analyze the cards, etc. He’s a very good friend. For me, he’s one of the only moviemakers that’s really a moviemaker. To make a movie, you must not only be able to tell a story, you must be able to a story in the movement of a picture. It’s different to tell a story in a novel, a comic … it’s like a dance. Do you remember the elevator scene in Drive? That’s great! He visualized the two sides of that character in that scene. On one side, he’s delicate, and the other side, he’s terrible!