Every age has its monsters. The Babylonians had the Scorpion men of Gilgamesh. The Egyptians had Osiris’ personal executioner, Shezmu, a Luca Brasi figure who delighted in crushing human heads in a wine press. The early Greeks sailed an Aegean sea rife with a phalanx of Cyclopes and Gorgons. The enlightenment produced Frankenstein, science’s first monster, spawn of Faustian alchemy, an argument for the limits on man’s incursion into the realm of God. In our age, at least the part since invention of the bomb, we have had Godzilla who, his many pretenders aside, stands alone.

Godzilla transcends humanist prattle. Very few constructs have so perfectly embodied the overriding fears of a particular era. He is the symbol of a world gone wrong, a work of man that once created cannot be taken back or deleted. He rears up out of the sea as a creature of no particular belief system, apart from even the most elastic version of evolution and taxonomy, a reptilian id that lives inside the deepest recesses of the collective unconscious that cannot be reasoned with, a merciless undertaker who broaches no deals. He arrives alone, the ultimate gunslinger, with a free will all his own, the greenest thing ever seen.

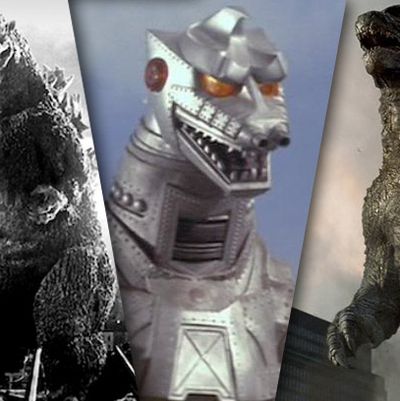

That said, even a 400-foot-tall monster can be said to have a history. With a brand-new $160 million version of Godzilla currently on view across the country, this might be an appropriate time to recap the Beast’s many manifestations since he first flattened Tokyo six decades ago.

The Early Years: The Nightmare

The standard liberal, i.e. “serious,” birthdate of the king of monsters is usually listed as August 6, 1945. As described in the great 1980 song by the Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, it was on that bright summer morning that a B-29 Superfortress piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, who named the plane after his mother, Enola Gay, planted the kiss that “will never fade away.” The A-bomb dropped on Hiroshima sent a flash brighter and hotter than a thousand suns, which, in addition to killing 100,000 people, caused a simple monitor lizard who was just minding his own damn business to mutate into a really pissed-off SaurusDude bent on global destruction.

The current Godzilla, despite some screenplay mumbo-jumbo about the monster’s alleged eternality, more or less accepts the bomb as the Beast’s incept date. Director Gareth Edwards’s trailer, debuted at the annual Comic-Con, featured Robert Oppenheimer, head of the Los Alamos Project, (mis)quoting Krishna in Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of Worlds.” In retrospect, the cause/effect is difficult to deny, especially when watching Inshiro Honda’s original 1954 Godzilla with its subtitles, elegiac score, and murky black and white that seems to peel from some far future Dead Sea Scroll. It seems important, a global cry for help.

This is all great in a Night and Fog kind of way for hitherto naïve folkies singing of the Hard Rain that’s supposed to fall, universally, but the first-generation Godzilla was more of a regional figure. The idea of Godzilla as exclusively an Atom Age metaphor would have been premature in the Japan of the early 1950s. It was less than a decade after the war. The Japanese eugenic project, aimed at establishing a ruthless hegemony of superiors over the nonentities to the West, had failed. The emperor was deposed, stripped of divine status. The homeland islands were occupied by a massive, doughy race of loud-mouthed, baseball-loving lugs that propriety demanded be treated as rightful victors. Still, this time of national guilt and humiliation produced some of the greatest movies ever made in Japan, or anywhere, films like Kurosawa’s Stray Dog and Ikuru. Honda’s first Godzilla, featuring Takashi Shimura as a fearful archeologist (a Kurosawa favorite, he’d play the lead in the sublime I Live in Fear), is in line with these inwardly turned post-war films and perhaps the most brutally unforgiving of them. Shame-ridden self-flagellation was in order, and who better to supply the rubber-suited psychic punishment than the Rorschach-shaped big fella himself?

Middle Eon: Befriending the Terror

During his movie-star period, Godzilla, the king of monsters resembles no one more than the king himself. Like his reptilian contemporary, Elvis was a force of nature, a race-mixing elixir straight outta Tupelo capable of putting people in touch with what they most craved and feared. Except then the Colonel stuck him in all those dumb pictures with Gig Young and Delores Hart (31 scripted films in 16 years!), which likely did little to decrease America’s single greatest singer’s dependence on Dr. Nick’s script pad. Appearing in 28 films in 50 years, Godzilla experienced a similar domestication, with his character often played for laughs and even verging toward Barney territory.

Aside from recollecting the sheer exhilaration of attending a 1975 showing of Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla in a packed, cheering, 4,000-seat theatre in downtown Manila, where the projectionists dutifully edit out everything except the fight scenes, I won’t attempt to offer description of Godzilla’s WWF/E era, when, from 1962 to 1995, he was routinely pitted against “heel” monsters like the three-headed Ghidah, the ratchet-armed Megalon, and most surreally, the gossamer Mothra and her two tiny singing princesses. Anything that can be said about these films has already been better articulated by the robot hosts of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and on YouTube series like Godzillathon, where narrator James Rolfe provides whiz-bang blow-by-blow accounts of the monster’s serial duke-outs with true, semi-moving fanboy love.

Many students of the Godzilla metaphor tend to dismiss these films as frivolous cashing in on the monster’s legacy on the part of rapacious Toho executives (no doubt true), but this is to overlook the deeper resonance the monster stirs in the heart of its adopted Japanese homeland. The embodiment of a rueful past and uncertain future would have to be met head on, and since Godzilla was basically indestructible, heartfelt apologies and eventual coexistence seemed the only way. The surprise was Godzilla’s magnanimity, his spirit of clemency and compassion. Not only would he forgive Japan for losing the war, but he would become the nation’s protector. He would allow himself to play the fool to the delight of children born into a world where a single press of a button meant apocalypse. Whoever imagined a beast marginally related to the serpent of the garden had such heart or sense of fun? The former destroyer became the savior. Still, it didn’t pay to become too comfortable. No matter how goofy he might seem, the tacit understanding is that the beast retained all his weapons, ready to turn radioactive badass at any unpredicted moment of time.

Late Zilla: Decadence and Return

Exactly when the puissance of the Godzilla metaphor began to run low is difficult to determine, but the publishing of William Gibson’s Neuromancer is reasonable mile-marker. It was a different world now, with rapidly dissolving borders and other kinds of anxieties. Plus, Godzilla was soon to be a monster without a country. Toho, whose copyright lawyers often equaled the fierceness of the monster himself, licensed his likeness to Sony, an agent of global capital. The monster-as-property had outlived the monster-as-meaningful-character. He was just another specimen in the blockbuster menagerie. No longer gallantly defending Japan from mental/moral pollution of “The Smog Monster,” which the Godzillathon narrator refers to as looking like “one gigantic turd,” the beast was now in the employ of internationalist interlopers and intellectual goniffs like Roland Emmerich, whose 1998 Godzilla, featuring an atomically “correct” version of the behemoth, had to be the low point.

This seemed the end, but once again a combination of world disaster and desperate subconscious called out across the unfathomed depths to stir the monster to action. This came in the form of the March 11, 2011 earthquake off the Japanese coast. With a Richter-scale magnitude of 9.0, it was the fifth-strongest quake ever recorded, generating far more power than any A-bomb, resulting in massive tsunami waves, some of them as high as 150 feet. The quake and flooding severely damaged the nuclear power plant at Fukushima, the most serious such event since the meltdown of Chernobyl. The many videos of the events, the vast waves sweeping boats onto shore, the spread of black water carrying hundreds of cars and trucks across the landscape, were far more wrenching than the most expensive CGI. Given the locale and nuclear component, it was a Godzilla movie without Godzilla.

In the wake of such an event, if Godzilla were to ever return to his former glory, it would be now. Which brings us to the new Godzilla, which, after a blanketing marketing campaign, opens this weekend. As for a review, see here, but from the point of view of the G-fan, someone who wrote a whole novel based on his essence, I find myself unsurprisingly unmoved. This isn’t because the film is less than an honorable effort, especially when given the vicissitudes of current moviemaking. There are plenty of perfectly respectable, even thrilling sequences. It is arty in the way the fancier Batman movies are. The director, Gareth Edwards, spends a lot of time in the program notes expressing his “reverence” for the Godzilla character, in that Speilbergian way of worshipping the things that touched him as a child. That is likely the problem. Despite much talk of Godzilla and his connection to the dropping of the bomb, the film is a museum piece, an homage to used-up trope. Things run their course, and Godzilla has run his. There was no compelling reason to bring him out of retirement for such a staid victory lap.

Indeed, if there is a current film that Godzilla could be compared to, it would be Noah, with Russell Crowe in the embattled title role. Again faced with the contemporary realities of the big-money filmmaking, director Darren Aronofsky trots out any number of Transformer “monsters” to fill out his otherwise Talmudical investigation of the flood story. But it is clear who the real monster is: God, the supposed supreme being who, seeing the world he made and finding it unsatisfactory, decides to smash it in the manner a petulant child knocks over a castle of blocks. Noah does his job here, following all those complicated instructions of how many cubits of this and that to use to build his boat, and he succeeds in repopulating the new world to be. But what all those innocents who died to satisfy God’s apparent whim? Who might they appeal to gain justice? Who might protect them? There’s an idea. Godzilla vs. Yahweh. Now that would be worth seeing.