Three years ago, the playwright and activist Larry Kramer stood outside the Golden Theatre during the Broadway run of his 1985 AIDS play The Normal Heart, which Glee co-creator Ryan Murphy has made into an HBO movie premiering on May 25. As teary theatergoers exited, he handed them a one-page “Letter from Larry Kramer,” which began: Please know that everything in The Normal Heart happened. These were and are real people who lived and spoke and died, and are presented here as best I could. Several more have died since, including Bruce, whose name was Paul Popham, and Tommy, whose name was Rodger McFarlane and who became my best friend, and Emma, whose name was Dr. Linda Laubenstein.

The character named Felix Turner — a closeted, dying New York Times fashion reporter who’s the lover of Kramer’s onstage alter ego, Ned Weeks — was missing from the letter. “If Larry wanted to keep this one piece of himself private,” says actor John Benjamin Hickey, who won a Tony award for his portrayal of Felix (played in the HBO film by Matt Bomer), “I respected the secret. I found it romantic.” But for readers of the “Style” pages of the Times in the early 1980s, Felix’s inspiration may have seemed obvious: Wasn’t he modeled on John Duka, the dashing reporter whose wry, often catty “Notes on Fashion” ran every Tuesday?

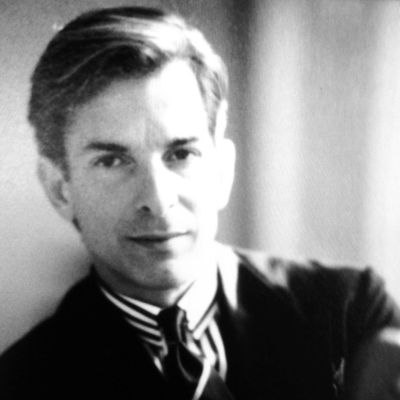

During his run at the paper, from September 1980 to February 1985, Duka established fashion as the nexus of New York high life. “Nobody in my era had the voice and influence of John,” says Nancy Newhouse, who hired him at the Times. The first Times stories about Marc Jacobs and Michael Kors were his. “You couldn’t wait for the column — it was the first thing you read,” recalls Fern Mallis, the former executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Duka’s chatty items seem modern even now — “he was the original blogger,” offers the artist Judyth van Amringe, who was a regular in his column. A 1981 item mentions the offerings at Saks thusly: “A look at the third floor found Adolfo’s boutique sparkling and filled with his new $1,200 tweed suits — arguably worth every penny. Next door, Saint Laurent’s new metallic gold leather skirts are in, for $700, arguably not worth every penny.”

In The Normal Heart, the Times reporter says he’s too busy to write about AIDS because he’s got to cover “twenty-three parties, fourteen gallery openings, thirty-seven new restaurants, twelve new discos, one hundred and five spring collections.” Another reason to avoid the subject was the paper itself, which, under A.M. Rosenthal, was a markedly homophobic place. As Felix says: “I just write about gay designers and gay discos and gay chefs and gay rock stars and gay photographers and gay models and gay celebrities and gay everything. I just don’t call them gay.” “That’s John exactly,” says Wendy Goodman, New York’s design editor, who worked with him at this magazine before he moved to the Times. “He transcended and traversed all these worlds. His homosexuality was interesting. John was openly gay at New York, and then he went to the Times, and he felt he could not be himself [there] as a gay man.”

Richard Kornberg, who was the publicist for the original off-Broadway production, theorizes that Kramer wrote the character to catch the attention of Seventh Avenue, which was in deep denial about AIDS. “A fashion-and-parties reporter is the type of person who gets out, whom Larry felt should have been out,” he says. With Felix, Kramer apparently took more artistic license than with any other character. After seeing the revival, I emailed Kramer to ask about Felix’s resemblance to Duka. His response was to the point: “Not talking about Duka and dispelling all notions that Felix is Duka.”

But the two men did have a history. Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library has 187 boxes of Kramer’s papers on deposit. In Box 59, I found his carbon copy of a letter to Duka that he’d typed on Christmas Eve, 1981. “I don’t understand people like you — people who are so selfishly inconsiderate of other people’s lives … You invited me to share last evening, and then you don’t even have the courtesy to phone me … You have been a very thoughtless friend too often … Go fuck yourself.” In Kramer’s datebook entry for the previous night, “No show” appears in red ink next to Duka’s name.

By the time the play opened, Duka had left the Times because his close relationship with a PR woman named Kezia Keeble was compromising his news judgment. Nevertheless, Rosenthal told Duka in a farewell memo that the columnist would “not be easy to replace. I am reluctant to see you go, but I wish you and your bride great success.”

The Times published the announcement of Duka’s wedding to Keeble eight days after his final column ran and two months before The Normal Heart opened, which effectively quashed speculation that Felix was based on Duka. “John was in love with Kezia — they were husband and wife,” says Josephine Wallace, who was helping Duka research a biography of Halston. “But I don’t know if they slept in the same room.” Together with Keeble’s ex-husband Paul Cavaco, they opened ran the fashion-publicity firm Keeble Cavaco & Duka (now KCD), with clients like Bergdorf’s and Yohji Yamamoto. The marriage was brief. Duka got sick in 1987 and died of AIDS 14 months later, in January 1989; Keeble died of breast cancer a year and a half after that. “One day he was there, and then he wasn’t,” says Wallace. “After he lost 30 pounds, he did not want to see anybody. Nobody died of AIDS in a way that was okay — John died sad, angry, and lonely.” “He had reached a pinnacle,” adds his twin sister, Jo-Anne. “He came from nothing and he was living on a 27-acre estate. He was hitting the height of his life, and then he was gone.” After playing Felix for 12 weeks on Broadway, Hickey developed enormous respect for the man who was a star at the Times in spite of the paper’s homophobic culture. “He was so fucking clever and on top of his game,” says Hickey. “He wasn’t going to let living in the closet stop him.”