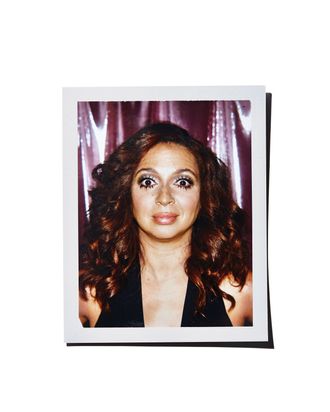

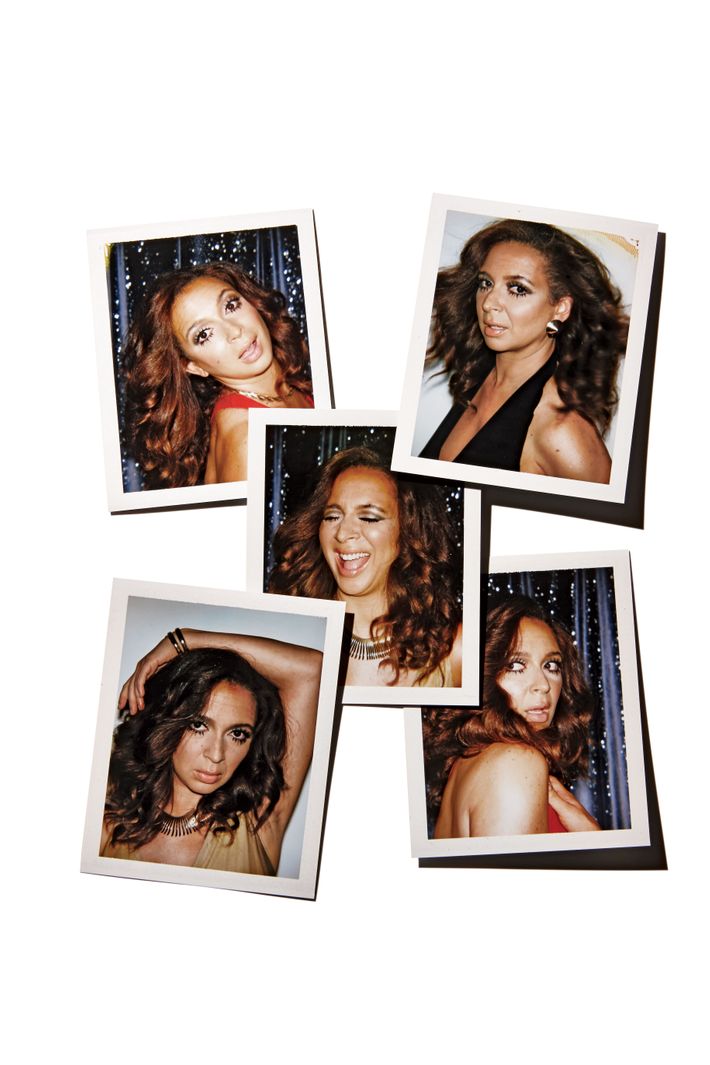

Photo: Lucas Michael/New York Magazine

In a matter of hours, the first—and possibly only—episode of The Maya Rudolph Show will begin filming in front of a live audience on Stage 44 of the Universal Studios lot, and despite the fact that she has some serious doubts about what will transpire once rehearsals are over (at this point in the day, “the show has the potential to suck hard”), Maya Rudolph has gone off script.

“You need to go do some crack?” she breaks character to ask Andy Samberg in response to a line about wanting to use the bathroom. A moment later, she turns to Fred Armisen, who wears his signature look of profound befuddlement.

“We-eeell,” she says in her character’s crazy voice. “I think he just took a deuce.” This time, the set erupts in laughter.

Of course, it’s unlikely that any of this silliness will make it into the final product. But this silliness is very much behind Rudolph’s reasoning for wanting to do a variety show in the first place—an undertaking that seems so earnest and archaic that, in today’s entertainment landscape, only a comic with Rudolph’s experience could hope to pull it off. In fact, she’s wanted to pull it off for years, having initially broached the subject in a meeting shortly after leaving Saturday Night Live in 2007. “Everyone said, ‘I think people love the idea of a variety show, but every time people do them they’re not received well,’ ” she tells me later. “Like, if you say ‘variety show,’ then people think you’re going to come out in a Cher headdress. And I love a Cher headdress—don’t get me wrong. But I didn’t even know how to get it started.”

Instead, she gave birth to three of her four children, voiced a few animated characters, starred in the TV show Up All Night, and appeared in various feature films, including the comedy event of 2011, Bridesmaids. Still, she’d sometimes be watching TV with her kids and stumble across old clips from The Carol Burnett Show, the viewing of which caused a pang of jealousy, even if they were filmed over 35 years ago. “When I left SNL,I wanted to work with my friends,” she says. “That’s what I missed the most. I saw her cracking up with her friends. They seemed like people you wanted to hang out with.”

Which is exactly how Rudolph herself has often seemed. From her first appearance on SNL, playing an MTV VJ in a leather bikini top (“In those days, my boobs were boobs, and not milk sacs that just kind of hang from the front of your body”), her knack for committing to the utter wild-eyed weirdness of her characters allowed for a rabbit-hole experience. Plus, she could sing. She could dance. She cavorted, to hilarious effect. So when Up All Night was “dying a very slow, painful death,” subject to low ratings and an ill-fated attempt to go from being a single-camera show to a multi-camera one, Rudolph went to executive producer Lorne Michaels to raise the subject of her variety show yet again. After the success of The Sound of Music Live, Rudolph says, “I was hopeful they’d be interested in giving it a shot,” and network chairman Bob Greenblatt “is very deeply rooted in musical theater, so he already loved it.” Even so, NBC put the idea in a kind of holding pattern. “Lorne talked about it as a thing we would do with Bob after pilot season, because it was a show that had to be created and wasn’t exactly a sitcom that you could write and then have everyone read. So we waited until NBC got all their ducks in a row with all their other programming. Then they let us do this,” Rudolph says. “And I also had to have my baby. That was the other part. I had to pop out a person.”

Eventually, said baby popped and NBC gave the green light for a one-off, hour-long special to air Monday, May 19, with the possibility of additional episodes in the future. (Unlike The Sound of Music, Rudolph’s variety show won’t be live, although most of it was filmed before an actual audience.) A couple of months ago, Rudolph got an office, started meeting with three writers, and began rounding up a cast that includes SNL cohorts Samberg, Armisen (“My comedy husband”), and Chris Parnell, as well as Craig Robinson, Sean Hayes, Kristen Bell (“My new favorite person”), and musical guest Janelle Monáe. But the cast didn’t gather for a table read until April, and rehearsals have been almost as manically fast-tracked as they were in Rudolph’s SNL days. Part of her fear that this show might “suck hard” is her knowledge that the best bits don’t come together until the cast does. (One sketch was born from an inside joke Rudolph and Armisen have shared for almost a decade.)

From behind the piano, Hayes wears sweatpants and a wide grin. Bandleader Raphael Saadiq taps out a rhythm on his knee between skits. And as Rudolph had hoped, the rehearsal has the air of an intimate hangout. “I think that’s a good cut,” Samberg says about one line adjustment. “Also, is it weird if we cut Fred from this?”

“I, uh, I don’t see a problem with that at all,” says director Beth McCarthy-Miller, playing along.

Armisen feigns panic. “I’m begging you, don’t—Beth, please don’t, don’t let that happen.”

“I’ll leave it to you,” Samberg demurs, as Rudolph looks on, grinning.

Finally McCarthy-Miller breaks, her laughter ringing out.

Rudolph waits for the group to settle. “Ready?” she asks. “Five, six, seven, eight.” She bursts into an impromptu song about finding true happiness.

“I really wanted to do what I’m doing for a living, and I really wanted to have a family,” Rudolph tells me the next day. “And it is not lost on me that I got really lucky that I was able to have these things that I wanted.” We’re having lunch in Studio City at a nondescript Japanese restaurant with an impressive Zagat rating and a waiter Rudolph knows well enough to rib.

“You’re very different during the day,” she tells him.

“Yes, every day my face changes. No, I’m just kidding!”

Rudolph smiles appreciatively. “At night he’s got like a stand-up routine. We’ve had some fun dinners.”

She orders the fresh scallops from Hokkaido (“Yes, please—as long as they’re from Hokkaido. That sounds far”) before rubbing her eyes with the palms of her hand. The day before had been so long her “bones really hurt.” After rehearsing into the afternoon and having a dress rehearsal in the evening, The Maya Rudolph Show had begun filming at 8:30 p.m. and wrapped three hours later, after which the cast had gone out to celebrate. “I drank Champagne, got home at 2:30. It was great.” Then she was up with her 8-month-old at 7:15. “Whenever you start the day changing a diaper, like unzipping someone out of Batman footies because their diaper leaked, that’s the start to a good day. That’s the real shit. Lit-er-all-y the real shit.”

In her telling, Rudolph’s own Westwood childhood was a bohemian paradise. “My parents”—songwriter and music producer Richard Rudolph and the late soul singer Minnie Riperton—“were hippies. Our house was always really funky. We had dogs with overgrown hair. The backyard always felt like a tropical jungle to me, but I think it’s just because it was really overgrown.” Some of Rudolph’s earliest memories are of watching her mother perform onstage (“Gorgeous, self-confident, one-of-a-kind”) when she and her brother went with their parents on the road. In high school, Rudolph befriended Jack Black, whom, she says, “I always had a crush on. He was like the theater god at my school. He was Pippin when we did Pippin. I was just one of the chorus in a unitard.” When she was 14, Black took her in his VW Bug (“He taught me how to drive stick. I know that sounds awful. It wasn’t meant to”) to see the improv troupe the Groundlings, with which she started studying when she graduated from UC Santa Cruz with a degree in photography. Her father had told her that she needed a plan. “I always had Saturday Night Live on the brain, and I noticed that the current cast—Will Ferrell, Chris Parnell, Chris Kattan, Ana Gasteyer, Cheri Oteri—a lot of them were Groundlings graduates.”

A few years later, SNL producer Steve Higgins came to see the group and invited Rudolph to audition for Michaels. “I ended up, after that, thinking, I’ll never work there. That was the worst interview I’ve ever had. He must think I’m an idiot. He asked me why I thought I should be on the show and I said, ‘Because I like to wear wigs.’ It was so pathetic.” Nevertheless, Rudolph was invited to New York to work on the last three episodes of the 1999–2000 season. “I always said it felt like starting school at the end of the year—everybody knew where to sit in the cafeteria, and I did not know. They brought me in on a writing night as my first day, which was Tuesday. And I said, ‘So, what do we do now?’ And Chris Parnell said, ‘Well, we write.’ And I said, ‘How long does everybody stay?’ And he was like, ‘Usually until like eight in the morning.’ Then I just remember everyone closing their office doors. They put me in an office with Zach Galifianakis, who was out there as a trial guest writer. He and I were both like, ‘What the fuck do we do?’ ”

It was during her tenure at SNL that Rudolph met Paul Thomas Anderson, and they had their first child. While she’s perfectly happy to talk about her career, it soon becomes clear that she’s even more happy to talk about babies. “I’m guilty of digressing to baby stuff,” she says, throwing her hands up in mock alarm. Like her second child, her fourth was born at home, half-accidentally, but half because “I knew I could do it. It’s the fucking most brutal thing ever, but then you get through it. I’m guilty of that thing where you have the baby and you’re like, ‘I don’t think I could ever do that again,’ and then one day you’re looking at your baby and go, ‘I miss having a tiny baby.’ Like, what?”

Still, she assures me that this last baby will truly be her last. Four days after giving birth to her, Rudolph found herself on the set of Anderson’s latest film, Inherent Vice, out in December. “It’s one of those things where you realize I obviously love this person because I would only say yes to him, but I also simultaneously want to kill him for asking me because he knows I’m not going to say no.” Luckily, it was only a small part requiring Rudolph to sit at a desk. “When I see my face,” she says, “all I can see is the water weight.”

In the end, The Maya Rudolph Show is largely Rudolph’s attempt at a life-work balance—“born out of a realization that I have children, and I fucking hated never seeing my kids.” As such, it’s more earnest than one might expect, a truly traditional variety show—with an opening number, a collection of sketches, and a lot of breaking into song—rather than some sort of tongue-in-cheek commentary on that format. “I love the good-mood, magical quality of it. I didn’t want to be terribly cynical or snarky.”

In both form and function, then, the closest modern-day analog is Rudolph’s SNL friend Jimmy Fallon’s offerings, those late-night–cum–variety shows that find their host singing, playing guitar, and performing in skits with an unapologetic tip of the hat to the variety extravaganzas of yesteryear. In fact, the similarity is such that it’s tempting to view Rudolph’s pilot as a glimpse into what it might be to finally have a female heading up a network’s late night. “Oh, I’m sure that will happen,” Rudolph tells me before going on to say that it’s not something she’d be interested in herself. “I never did stand-up, and I don’t think I’d be good at it at all. Plus, I’m a ham. I would want to be singing dumb songs more.”

Instead, she wants to do more painting. “I know that sounds really corny. That’s such a mom thing, like”—she takes on a breathy voice—“ ‘I started painting again.’ Or: ‘I went back to my pottery class.’ But I’ve always loved drawing, and I fell in love with my baby’s face when she was like 8 months old, so I just started painting the kids.” She smiles over her sashimi. “I have the soul of an old lady in a cardigan sweater.”

When The Maya Rudolph Show airs, its ultimate fate will, of course, largely be determined by the number of people who tune in. But even with a ratings boon, Rudolph doesn’t envision it as a weekly occurrence. “In a perfect world, I’d like to pace it a little bit so that it doesn’t lose its quality of feeling like, Oh, this nice thing came back.” Whether it comes back or not, The Maya Rudolph Show is already a success, at least as far as Maya Rudolph is concerned. She’d gone to sleep the night before “buzzy” with relief at how it had all gone off. “We had a lot of fuck-ups and a lot of cue-card problems. We didn’t know until very recently if we were going to be able to pull it off. But it was fun. It actually felt like a show.” And while her kids weren’t there (“You want them to see that stuff, and they want to eat ice cream”), it still sort of felt like a family event.

At one point, waiting to go onstage for a sketch, she started lactating, but not enough to leak through her costume. “I was like, ‘My milk just let down,’ and Fred was like, ‘What’s that like?’ And I was like, ‘You know when your foot falls asleep and gets tingly?’ ” She laughs. “ ‘It’s not like that.’ ”

*This article appeared in the May 5, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

Maya Rudolph on Fulfilling a Variety-Show Dream