“Money is like blood: It gives life if it flows. Money is like Christ: It blesses you if you share it. Money is like Buddha: If you don’t work, you don’t get it.” These words are spoken directly to us by Alejandro Jodorowsky himself in the opening images of The Dance of Reality, as shots of gold coins are superimposed over his face. For the 85-year-old director, it’s a typically bold and cryptic way to start a film — especially since The Dance of Reality isn’t really a movie about money at all. Those opening lines serve less as a statement of themes and more as an incantation, the way some films from the Muslim world open with a prayer. I finally found some money to make another movie, the cult director of El Topo and The Holy Mountain seems to be saying to us, explaining his 24-year absence from the world of features. And I don’t care if I blow it all and never make a dime.

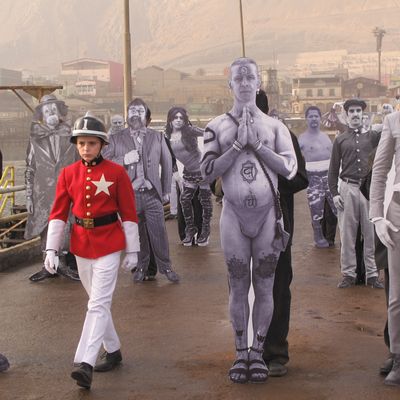

Set in 1930s Chile, The Dance of Reality is a cinematic memoir, an exploration of Jodorowsky’s painful childhood in dirt-poor Tocopilla, which is somehow both a desert town and a coastal one. The Jodorowskys, descended from Ukrainian Jews, are perpetual outsiders. Shy young Alejandro (Jeremias Herskovits) feels under siege from all sides: His ample-bosomed mother (Pamela Flores), who sings all her lines in recitativo fashion (a nice Jodorowskian touch, that), makes him wear a long blonde wig and keep alive the sensitive spirit of her late dancer father. Meanwhile, Alejandro’s father Jaime (Brontis Jodorowsky), a uniform-wearing communist shopkeeper and volunteer firefighter, fixates on acts of manhood: He tickles the boy and forbids him from laughing; he slaps him and makes him ask for more.

Even so, the film depicts this patriarchal taskmaster with tenderness. Jaime is not a monster, but an anxious man clearly hiding his own insecurities in a cloak of machismo: When the son, after seeing a man burned alive in a fire, breaks down, the father frets about what his fellow firemen will think. “Even dressed as a fireman, a Jew is a Jew!” he imagines them saying. It’s the 1930s; the line between acceptance and murderous ostracism is a thin one. More important, Dad doesn’t want any suspicion falling on him because he’s a member of a secret anarchist group, and he’s out to kill Chilean dictator Carlos Ibanez.

This is a stirring and strange mix of history, memory, and fantasy. If in his earlier films, Jodorowsky borrowed the structures of genre (the Western in El Topo, the Quest narrative in The Holy Mountain, the psychological thriller in Santa Sangre), here he borrows from the language of therapy. During especially painful moments in Alejandro’s life, the director, playing himself, embraces his younger self, speaking to him about the importance of persevering. On paper, it may sound didactic and overtly self-helpy, but Jodorowsky’s poetry — both the spoken and the cinematic kind — renders it delightfully alien. “All you will be, you already are,” the elder Jodorowsky whispers. “Everything you will become is within you already.” In the film’s most stirring sequence, the child contemplates suicide as his older self begins to enact a soft, ritual-like dance with him. “For you, I don’t yet exist. For me, you no longer exist anymore,” the man whispers to the boy. The power of the scene is a curious one: It lies not just in young Alejandro’s despair, but also in the older man’s loss. Neither of them seems fully whole.

Jodorowsky’s fondness for the surreal and grotesque is in full evidence here. What makes his films so captivating, however, isn’t their strangeness, but their refusal to divide the world into good and bad, even when it’s easy to do so. At one point, young Alejandro is kind to an impoverished miner who lost his hands in an explosion. (Like every Jodorowsky film, Dance of Reality teems with real-life amputees and other handicapped people.) When he sees the boy embracing the destitute, crippled man, Jaime becomes angry — upon which the amputee, who otherwise seems like a prime candidate for cinematic holiness, launches into an anti-Semitic tirade. Everybody is contaminated with sin, in other words, and even the seemingly kindest person can turn on a dime. It seems like a dark vision of the world — and I suppose it is — but it also suggests that within that capacity for cruelty also lies the possibility of grace. We’re all hovering somewhere in between, Jodorowsky seems to suggest, spiritual refugees lost between our past and our future, between our worst and best selves.