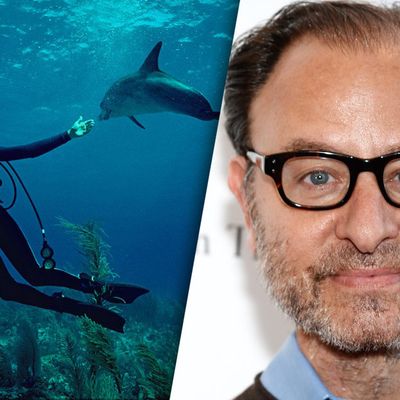

When filmmaker-actor Fisher Stevens met Sylvia Earle for the first time, he couldn’t comprehend the idea that she wasn’t already on his radar. Stevens was a producer behind the exposé The Cove, about dolphin hunting in Japan, and yet was only just learning of Earle’s incredible story. At 78 years old, she is one of the world’s top marine biologists, explorers, and environmental advocates — a job she began in the 1950s. One glimpse of Earle in action and Fisher knew he couldn’t leave her side. So he didn’t.

Fisher’s latest directorial effort, Mission Blue (which premieres exclusive today on Netflix), is part character study, part nature film, and part activist call-to-arms, hoping to “ignite public support for a global network of marine-protected areas.” From Los Angeles, where fellow environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio was set to present a screening of Mission Blue, Fisher told Vulture about assembling Earle’s life story into a gripping, inspirational tale, how Florence + the Machine became the marine biologist’s musical proxy, and how filmmaking has affected his acting career.

Sylvia’s name popped up a few times during your press rounds for The Cove. How did you decide to build an entire movie around her?

I ask myself that every day. Basically, I was asked to film a trip that she was taking to the Galapagos Islands with TED [of TED Talks]. They gave her a prize. She took 100 people on this boat — philanthropists and scientists — trying to get people to understand how important it is to save these oceans. She had this dream to create these marine-protected areas, hope spots, and wanted to have wealthy people and scientists get together to have a dialogue to maybe start foundations and make things happen. I filmed that, and was going to make a short film about the hope spots. I realized that’s kind of a boring movie. But I did an interview with her in Berkeley, and there was this box under her bed, and in it were all these archival films. We realized we needed to tell this woman’s story. It deserves to be made. She’s a pioneer in many ways. Not just because she’s been fighting for the oceans, but she’s a pioneer for females, women scientists, women marine biologists.

You produced The Cove with an idea that it could feel like a thriller. Was there a similar genre idea for Mission Blue?

Yes, but it’s more difficult with this film. We don’t have sneaking-into-the-cove footage. We have Sylvia going into the water among these huge fishing boats and almost getting sucked up by a vacuum. We have her diving in the coral sea when the sea was rough. In that sense, we wanted big, epic shots, and we got them. That’s in my mind. The beauty of the archival is that it takes you back to a different, simpler time. It was so different back then. You see how quickly we’re moving as a species. And how quickly the oceans are depleting. We never thought we could hurt the oceans. As Sylvia says, now we know. Some people knew for 30 years.

I think at some point, Sylvia says, “In the water, anyone can be a ballerina. Anyone can stand on one finger.” And I thought, maybe there’s dance inspiration here, some sort of musicality to the way you’re making this movie.

Honestly, my editor Peter Livingston and I always talked about having a water ballet for Sylvia because she’s just so graceful. And he found that line in our interview, and that was it, and then we were like, “Oh, that is just so inspiring.” Our composer Will [Bates] wrote this kind of water ballet, exactly what you thought, for her, and then we kept recutting and tweaking that scene. That scene was like four minutes at first, because we just got so mesmerized by her. So we just took it down, took it down, took it down. But music is a very important component in this film. I definitely think [in] documentaries, music is crucial — especially when you don’t have a script, it helps push stories along. Whenever I make a film, I just try as much as I can to keep every moment of the music right. Sometimes you don’t always hit it. I’ve driven composers possibly crazy by having them redo things, redo things, redo things. I can’t push my luck always, because we’re not paying the big Hans Zimmer bucks.

You end the finale with a heavy-hitter: Florence + the Machine’s “Never Let Me Go.” That was like a perfect match.

Yeah, when Netflix saw this film in Berlin, the ending wasn’t like that. The ending wasn’t really working. It needed more of a big pump — a bigger ending with a big song. Honestly, I was not happy with it, and thank God they gave us a little money to redo some graphics and some [of the] ending and my voice-over. I’d always had that song in my head. I’d always thought [Florence] was kind of the voice of Sylvia. We were having trouble getting the song. Leonardo DiCaprio wrote her a letter, and she gave us the song. We were lucky.

DiCaprio is pulling lots of strings for this one.

The thing is he’s an environmental friend of mine, so I think he cares about this stuff. So, he definitely helped us getting that song, because that wasn’t easy.

You interviewed James Cameron, who just released a pro-ocean documentary focusing on his one man dive to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. He mentions in your film the sacrifices it takes to be a modern explorer, reflecting Sylvia’s marital problems over the years. Cameron has seen relationships come and go in his own life — was he opening up to you there, onscreen and off?

I think that’s part of it. I think also he really admires her and respects her and feels that Sylvia was one of his inspirations. I think he gets the importance of exploration. She is a true National Geographic explorer, you know? There are not many of them. To do what Cameron did … I have beyond respect for that guy, because that is terrifying. And Sylvia wants to do that. She was trying to become one of the people to go down there. They have courage that I will never have, because that, to me, that is going to a place that is unknown. It’s like going to the moon. These people really crave that. I mean, I crave knowledge. I get really excited by learning about things that I care about, like the oceans, but I’m not one that’s gonna leave my family and go climb the Arctic or go down to the deepest place on Earth. Sylvia and James Cameron have that in them.. James Cameron gets that Sylvia is one of those people. They are a different breed. Sylvia’s still in the Guinness Book of World Records, I believe. Deepest single solo untethered dive.

We see footage of Sylvia resigning from her position as chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. She can’t help the environment from inside the bureaucracy, so she leaves. It’s a big moment, but she’s not especially emotional during it. Even when you’re talking about her marriage falling apart, Sylvia is concrete.

Yeah that’s a challenge always, when your documentary subject doesn’t want to show too many feelings. Sylvia’s a very put-together woman. She’s used to being on camera and doing it a certain way, and that was definitely one of my challenges, getting her to talk about her ex-husband. She didn’t want the film to deal with her personal life at all. She really didn’t. And to her credit, she trusted me enough to go there. And I really appreciated it, because I thought if we could see an emotional person, or see her life story, that will make people care more about the ocean.

How did you wind up as one of the Society of Golden Keys concierges in Grand Budapest Hotel?

I’m a world traveler, and I love Europe. I ended up hanging out a bunch of times with Wes Anderson in Paris. We became friends, and he asked me to do this small role. And it was not a big role — I mean, you blink and I’m gone — but you do movies for three reasons: the experience — that’s the most important — and then, you sometimes, if you need the money, you do one (this wasn’t for this); and you do a movie to work with great people. Those were great people. And he’s always been one of my favorite filmmakers, so it was just a pleasure to get to hang and do that movie.

Documentaries can take a few years to hammer out — do you have another in the works already?

Yeah, I’m working on one with Louie [Psihoyos], the guy I did The Cove with. We’re calling it, like, Six or Extinction Six, but it’s really exciting. And hopefully we’ll premiere and be ready to show in January, but it’s quite good, and that’s what I’ve been working on nonstop for the last three months. It’s about extinction — of species and of man.

This is a question Stephen Colbert asks Sylvia in the film: Do you eat fish anymore?

I eat very, very little fish. If I’m in a town where something locally has been caught by a pole, and it’s a smaller fish, I eat it. I eat lake fish. I basically cut down on almost all my other fish. I don’t eat any more tuna, I don’t eat any large fish. I became a pescatarian about ten years ago, when I didn’t know Sylvia and didn’t know any better. And I ate tons of fish and I got sick, I got mercury poisoning. So I learned a lot the hard way. Unfortunately, I still eat a little meat. That could be a whole other movie. The agriculture business and the meat business, and — I don’t even want to get into that.

Can of worms. Similar to The Cove, Mission Blue keeps coming back to the problem of fishing and fishermen. Are you having an existential crisis because your name is Fisher?

Yeah, I do. That’s why Sylvia first got along with me, she said, “Fish! How could I not love a man named Fish?” And that’s when we hit it off.

Your character on Early Edition was named Chuck Fishman.

They rewrote the last name when I got the part!