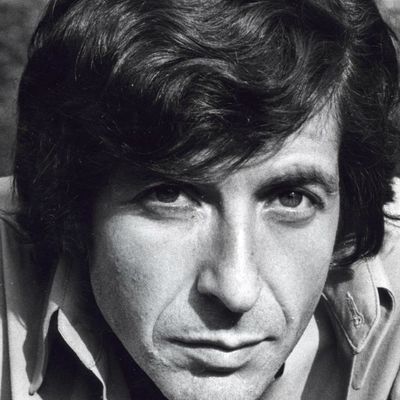

On September 21, Leonard Cohen turned 80. At an age where most people are happy just to be able to make it down to the shops and back unassisted, Cohen celebrated his birthday with the release of a new studio album, titled Popular Problems. It’s the 13th album in one of the most celebrated and fascinating musical careers of our time. It seems like a fine time to reflect on his discography — so here are the great man’s 12 studio records to date, ranked from worst to best.

Recent Songs (1979)

Our hero has never really made a flat-out bad record, but Recent Songs found him at something of a creative impasse. After the somewhat disastrous experiment of recording with Phil Spector (on which we’ll say more shortly), he returned to his trademark folk-influenced sound. And his heart didn’t really seem to be in it, because Recent Songs is a mishmash of sounds and influences. The fact that Cohen rarely plays anything from this record live these days speaks to his own displeasure with the result.

Various Positions (1984)

Everyone knows this as the one with “Hallelujah” (and perhaps to a lesser extent, the one with “Dance Me to the End of Love”). Beyond those two songs, though, there’s a sense that Cohen was treading water here. Nearly two decades into his career, he seemed ripe for a creative reinvention, which would arrive four years later in the form of “I’m Your Man.”

Death of a Ladies’ Man (1977)

This album gets a pretty raw deal from Cohen fans. It’s certainly true that Phil Spector’s production methods are an awkward fit with Cohen’s songs, making for a strange listening experience (it’s like hearing Leonard Cohen’s Christmas album), and the sessions for the record were … fraught. Famously, Spector pulled a gun on Cohen, pressing it to the singer’s neck and proclaiming, “Leonard, I love you.” (Cohen’s characteristically droll response: “I hope you do, Phil.”) But despite the strangeness of it all, there are some fantastic songs here, especially the epic title track and the startlingly bleak “Paper Thin Hotel.”

Songs From a Room (1969)

Cohen’s second album didn’t quite match the glory of his first, but it’s one worth revisiting if you haven’t heard it for a while. Opening track “Bird on a Wire” is quite possibly the most poetic way anyone’s ever conceived of saying, “Look, I fucked up and I’m sorry.” But this album’s best moments are generally the ones where the lyrics eschew personal reflections for storytelling: “Story of Isaac” is, indeed, the biblical story of Isaac, while “The Partisan” tells the story of a French resistance fighter during WWII, and “The Butcher” — one of the strangest songs in Cohen’s catalogue — seems to be from the perspective of Jesus (and, amongst other things, catalogues him shooting heroin).

New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974)

The last record of the first part of Cohen’s career, if you will. It’s a difficult piece of work to get a handle on — sonically, it’s a transitional record, moving away from the simple arrangements of his early work to a bigger, more orchestrated sound. Lyrically, the tone is curiously ribald — “Is This What You Wanted” name-checks KY Jelly, “Chelsea Hotel No. 2” famously narrates getting a blow job from Janis Joplin, and “Field Commander Cohen” describes how Leonard would amuse himself slipping acid into the punch at fancy parties. It’s something of an underrated record, overshadowed by what had gone before and what was yet to come.

Old Ideas (2012)

Cohen’s most recent album is the most “old-style Leonard” album he’s made in decades — the songs and arrangements here would sit comfortably with his mid-’70s output, although the lyrics are shot through with the wisdom of a man well into his 70s. (Particularly fascinating is opening track “Going Home,” which takes the form of a monologue from some higher power, reflecting on how the narrator “love[s] to speak with Leonard.”) There’s nothing here to rank with his very best work, but there’s nothing wrong with it, either.

The Future (1992)

The last record before our hero took to the mountain for a decade was a dark, world-weary affair — the title track proclaims, “I have seen the future, brother/ It is murder.” Musically, The Future is a curiously mixed bag. Its strongest tracks are up with the best work Cohen’s ever made, most notably “Anthem,” which is certainly a contender for Best Leonard Cohen Song Ever — he described the closing lines of the chorus (“There is a crack in everything/ That’s how the light gets in”) as “the closest thing I could describe to a credo.” But the record’s padded out by a couple of largely superfluous covers and, strangely, an instrumental, the only one of Cohen’s career.

Dear Heather (2004)

The Leonard Cohen experimental record! This is a curiously underappreciated entry in Cohen’s canon — the songs are great, and the music traverses an impressively wide range of sounds, from the traditionally Cohen-esque “The Faith” and “Nightingale” to tracks like “Morning Glory” and the title tune, which deploy decidedly unconventional song structures and unusual arrangements. “Villanelle for Our Time,” meanwhile, abandons music entirely for the first couple of minutes of its running time, leaving Cohen to recite the titular villanelle unaccompanied.

Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967)

Cohen was in his 30s by the time he released his debut album, which proves that it’s never too late to start something, and also perhaps explains why it was such an accomplished and assured piece of work. No one had written songs quite like this before, or certainly not in the field of pop music, anyway — the lyrics were dense and poetic, so heavy on imagery and allusion that people still scour them for meaning nearly half a century later, and yet somehow, they were also accessible and emotive. The highlights are well documented — “Suzanne,” of course, along with “So Long, Marianne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” — but there really isn’t a bad song here.

Songs of Love and Hate (1971)

The greatest accomplishment of the early part of Cohen’s career. As its title suggests, the album divides into a “love” side and a “hate” side, neither of which are particularly easy listening. The love songs contemplate affairs that have fractured and broken, damaging their participants in the process: two lovers who can never be together (“Let’s Sing Another Song, Boys”); Joan of Arc and the fire that consumed her (“Joan of Arc”); and, most memorably, a strange love triangle (the peerless “Famous Blue Raincoat”). The “hate” side, meanwhile, is pretty much the most desolate Cohen ever got — people who call Cohen’s songs “depressing” generally only reveal that they’re not listening carefully enough, but one could be forgiven for being somewhat downcast by listening to “Avalanche,” “Last Year’s Man,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” and “Diamonds in the Mine” in quick succession. Of course, that doesn’t stop you from wanting to listen to them again, and again, and again.

I’m Your Man (1988)

The great reinvention. From the opening bars of “First We Take Manhattan,” it’s clear that I’m Your Man is very different from anything Cohen had made to this point — out went the finger-picked acoustic guitar, in came copious synths and distinctly danceable bass lines. The lyrics found Cohen in playful form, too, indulging his oft-underrated sense of humor more than he’d ever done before: “Tower of Song” was a wry, self-effacing reflection on advancing age and his career to date, while the aforementioned “First We Take Manhattan” found him chuckling cryptically about monkeys and plywood violins. And yet, beneath the new veneer, the songs were as moving and beautiful as ever.

Ten New Songs (2001)

As the 1990s turned into the 2000s, the last the world had heard of Leonard Cohen was that he’d retreated to the Mount Baldy Zen Center and had been ordained as a Buddhist monk. There was no indication that he’d ever release another album — it was almost a decade from The Future, an album pretty much everyone had assumed was his swan song. And then, out of nowhere, this. Ten New Songs is a late-career masterpiece, with arguably the strongest and most coherent collection of songs on any Cohen record. Those songs catalogue its creator’s descent from the mountain back to the world — it’s an album that finds him, in his own words, “back on Boogie Street.” There’s a sense that his years of seclusion brought insight, if no ultimate conclusions — the album looks gravely on the state of the world, although the visceral disgust of “The Future” has been replaced with a calmer, more compassionate brand of reflection. There’s also a newfound sense of levity, and it seems significant that the depression that he’d experienced for most of his adult life apparently disappeared of its own accord in the run-up to recording Ten New Songs. The contrast between dark and light is best embodied in the sublime “Alexandra Leaving,” a song about resigning oneself to the end of a love affair that’s run its course, and resolving to appreciate the love that was shared instead of mourning their loss. If there’s a message here, it’s that life’s meaning is whatever you choose it to be, and that you can take comfort in the fleeting moments of beauty that life has to offer. If you’re going to take an idea away from a record — or, indeed, an entire discography — you could do a lot worse.