Each month, Boris Kachka will offer nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

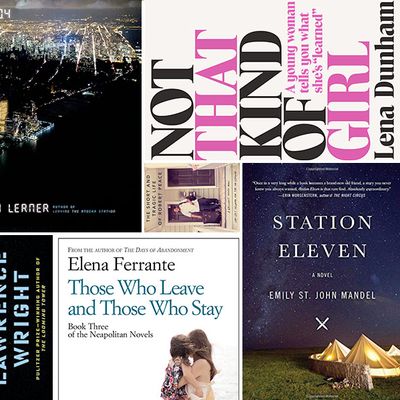

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, by Elena Ferrante (Europa, September 2)

Having taken on a pseudonym that inspires Pynchon-level conspiracy theories, the Italian novelist ÔÇö whoever she (he?) is ÔÇö may not want fame, but she deserves it. This third installment in her Neapolitan series, which tracks two friends on divergent paths ÔÇö urbane writer Elena and self-taught dropout Lila ÔÇö finds them navigating the age of motherhood and activism. (ItÔÇÖs the ÔÇÿ70s, and Italy seems to be breaking apart.) Start with the first book, My Brilliant Friend, and youÔÇÖll be caught up before the fourth and final installment makes its way into English. ┬á

The Bone Clocks, by David Mitchell (Random House, September 2)

James WoodÔÇÖs recent review of the authorÔÇÖs sixth ambitious novel may have hacked at his use of fantasy; it also acknowledge that Mitchell leads a generation of novelists thriving at the intersection of the personal and cosmic. And what matters about Mitchell ÔÇö here as ever ÔÇö isnÔÇÖt the labyrinths, the fallen world, or the epic battles between immortals. ItÔÇÖs the fact that he loves his humans. Hardy mortal Holly Sykes, whose life spans the book, is our guide from humble Thatcher-era Kent all the way to an apocalyptic 2040s Ireland, but the other players, many borrowed from his earlier books, expose a vast and growing cosmology that has more to say about our world than the world beyond.

10:04, by Ben Lerner (Faber & Faber, September 2)

Possibly the first piece of fiction to turn on Superstorm Sandy, LernerÔÇÖs second novel is more cerebral than his cult-favorite debut, Leaving the Atocha Station, but more mature. Again, weÔÇÖre inside a young artistÔÇÖs brain: neurotic and self-involved, but smart and honest enough to know it. This time, a writer struggles to make real human connections and to resist the dictates of publishers in the wake of, yes, a cult-favorite debut. ItÔÇÖs not just fun and games ÔÇö Lerner is a thoughtful flaneur, like early Auster ÔÇö but it does contain the cleverest reuse of an already-published short story youÔÇÖre likely to read in a novel.

Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel (Knopf, September 9)

Mandel comes by a now-common genre mash-up, highbrow dystopia, honestly, following three small-press literary thrillers. By focusing on a Shakespeare troupe roving a post-pandemic world of sparse communities, she brings a hard-focus humanity to the form. Repeated flashbacks to the life of an early flu victim, a Hollywood actor who dies onstage in the character of Lear, provide both comic relief and the pathos of a beautifully frivolous world gone by.

Thirteen Days in September, by Lawrence Wright (Knopf, September 16)

The author of engrossing deep-dives into Al Qaeda (The Looming Tower) and Scientology (Going Clear) stalks a subject less immediate but equally urgent ÔÇö the Egypt-Israel peace brokered by Jimmy Carter at Camp David in 1978 ÔÇö emerging with something like a potboiler of statecraft. In fine sketches of the personalities ÔÇö not just Carter, Sadat, and Begin, but their eccentric minions ÔÇö Wright shows just how difficult it was to achieve a lasting truce, and makes old news only more relevant in a region where something new happens every day but nothing really changes.

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace, by Jeff Hobbs (Scribner, September 23)

No one can really answer the question that tugs at this painfully sad book: How could its subject (raised in NewarkÔÇÖs blight, his father imprisoned for murder) graduate from Yale, determined to excel, only to die in a drug-related murder nine years later? The author, his college roommate, demonstrates the tensions at play, both personal and social ÔÇö the allure of the street as well as the dream of escape ÔÇö staying true to both PeaceÔÇÖs complicated life and the implacable drags on social mobility.

Not that Kind of Girl, by Lena Dunham (Random House, September 30)

What we know of DunhamÔÇÖs tightly held memoir in essays (from a published excerpt and a reading of her introduction) is so promising that its full publication risks triggering the next backlash. On the evidence, the Dunham of this book is neither a Hannah-like narcissist nor a feminist next door coasting on easy quips. Instead, sheÔÇÖs one of those precocious Manhattan tweens grown up, a drier and more evolved Woody Allen: savvy, maladapted, and bizarrely magnetic, carrying the torch of urban neurosis for a new generation.

On Immunity: An Inoculation, by Eula Biss (September 30)

The echo of Susan Sontag in the title of this brief but discursive social history of vaccination feels a little on-the-nose. Never mind: Biss earns the comparison between the covers. With beautiful writing and a firm grounding in literature, class, and medicine, she successfully wrenches a divisive and surprisingly nuanced topic away from our loudest, dumbest voices. (Spoiler: She supports vaccination.) YouÔÇÖll never look at swine flu, childbirth, or vampires in the same way again.