Each month Boris Kachka will offer nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible because they are all worth it.

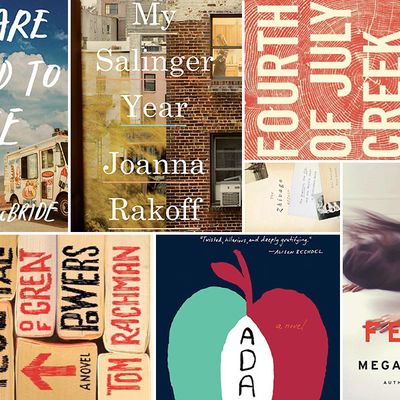

1. The Fever, by Megan Abbott (Little Brown, June 17)

The writer of stylish mysteries returns to the teen-noir milieu of her last novel, Dare Me, with a story loosely based on a recent case of mass hysterical illness in upstate New York. The new novel subtly evokes the creepy atmospherics of Twin Peaks or the more recent (and apropos) Top of the Lake.

2. Adam, by Ariel Schrag (Mariner, June 10)

The lesbian graphic memoirist, a successor to Alison Bechdel, breaks out with a novel somewhat conventional in form — California boy crashes with sister in Bushwick, comes of age, and falls in love — but completely radical in capturing the gender blur of 2014 gay New York. Adam, you see, is repeatedly mistaken for trans, and decides to play along in pursuit of his supposed soul mate, a gay woman.

3. Fourth of July Creek, by Smith Henderson (Ecco Press, June 3)

The debut novelist comes bearing a blurb from Philipp Meyer, author of the best-selling Old Texas epic The Son, and the connection is easy to see. Here too is a personal family story written in muscular, laconic prose, which quickly balloons to encompass, and diagnose, an illness at the heart of American life. But in Henderson’s novel, the malady is contemporary — the rot of rural poverty, warped by drugs, survivalism, and bastardized Christianity — and the story told through the eyes of Pete Snow, a Montana social worker trying to head off a Waco-size standoff.

4. We Are Called to Rise, by Laura McBride (Simon & Schuster, June 3)

A downtrodden social worker is only one of a small chorus of narrators — all based in the struggling outskirts of post-boom Las Vegas — that make up McBride’s more mosaic approach to social fiction. A 12-year-old Albanian-American boy trades letters with an Iraq veteran; a mother frets over her young adult son, another traumatized soldier. The consequences of war at home, and the possibility of community in our most atomized places, form the heart of a novel that’s by turns hopeful and tragic, but never maudlin.

5. The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book, by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée (Pantheon, June 17)

A work of deep historical research that reads a little like Le Carré, this is the backstory of the foreign publication of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago, and it bears its multiple burdens lightly: a sideways biography of Pasternak; a psychological history of Soviet Russia; a powerful argument for the book as literature; an entry into the too-small canon on the CIA’s role in shaping culture. In new reporting on the Agency’s distribution of the book behind enemy lines, the authors show how both sides in the Cold War used literary prestige as a weapon without resorting to cheap moral equivalency.

6. The Rise and Fall of Great Powers, by Tom Rachman (Dial Press, June 10)

Don’t fear the quirky female heroine tripping back and forth through time and space, on a journey to reconstruct a far-flung past stuffed with eccentrics. Rachman’s second novel only mildly resembles (and markets itself as) the whimsical, history-schmeared kin of Foer and his ilk. Rachman is too careful a sketch artist of both the micro (finely drawn characters) and the macro (wild subplots that miraculously cohere at the end). What he produces is more like light Dickens — if Dickens’s heroes had access to airplanes and the internet.

7. J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, by Thomas Beller (New Harvest, June 3)

8. My Salinger Year, by Joanna Rakoff (Knopf, June 3)

A year after the release of Shane Salerno and David Shields’s scandalous biography (along with a much-derided companion docudrama), two more personal and sympathetic takes prove worthy (if minor) correctives. Beller’s is the closer book to proper biography, though blessedly free of Salerno and Shields’s horn-blowing. J.D. Salinger is slim, discursive, and shot through with tales of the quest itself, à la Geoff Dyer. Relying on interviews, artifacts, and the notoriously suppressed original manuscript of Ian Hamilton’s 1988 biography, Beller has his affectations, like long, David Foster Wallace–style footnotes. But then, so did Salinger, and the affinity and affection is clear throughout. Rakoff’s book is much more a memoir than a biography — the story of how the young grad-school dropout found her footing among the New York literati while colonizing Williamsburg and working for the literary agency that represented Salinger. Rakoff doesn’t reveal much about her “subject” that we don’t know, but her inset portrait of him draws on something Beller never had: repeated written and phone contact with the man himself.