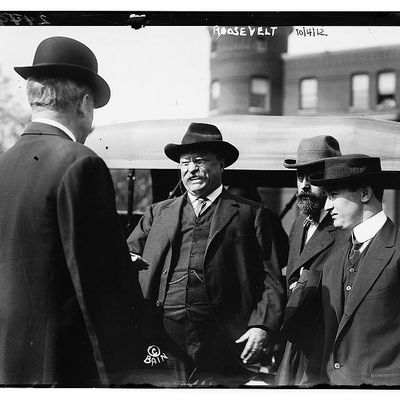

The Roosevelts, a new PBS documentary by director Ken Burns, presents President Theodore Roosevelt as a political superhero. In photo after photo, BurnsÔÇÖs famous pan-and-zoom effect magnifies RooseveltÔÇÖs flashing teeth and upraised fist. The reverential narrator hails his fighting spirit and credits him with transforming the role of American government through sheer willpower. ÔÇ£I attack,ÔÇØ an actor blusters, imitating RooseveltÔÇÖs patrician cadence, ÔÇ£I attack iniquities.ÔÇØ

Though exciting to watch, BurnsÔÇÖs cinematic homage muddles the history. Roosevelt was a great president and brilliant politician, but he was not the progressive visionary and fearless warrior that Burns lionizes. He governed as a pragmatic centrist and a mediator who preferred backroom deal-making to open warfare. At the time, many of his progressive contemporaries criticized him for excessive caution. The ÔÇ£I attackÔÇØ quote, for example, came from a 1915 interview in which Roosevelt defended himself from accusations that he had been too conciliatory.

Two Republican titans dominated Congress during RooseveltÔÇÖs presidency: Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, a suave associate of J. Pierpont Morgan; and House Speaker ÔÇ£Uncle JoeÔÇØ Cannon, an irascible reactionary from rural Illinois. Rather than challenge their authority, Roosevelt cooperated with them to accomplish what he could. ÔÇ£Nothing of value is to be expected from ceaseless agitation for radical and extreme legislation,ÔÇØ he reasoned.

RooseveltÔÇÖs compromises enabled him to achieve some incremental reforms, but the results were often flawed. Congressional leaders made a show of cooperating and then diluted his initiatives in committee. When he asked Congress to regulate the railroad industry, Senator Aldrich engineered the Elkins Act of 1903, a toothless bill drafted by the general counsel for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Even RooseveltÔÇÖs celebrated trust busting exhibits his preference for compromise. BurnsÔÇÖs narrator describes how he proudly defied J. Pierpont Morgan but neglected to mention that he sued far fewer trusts than his conservative successor, William Taft. For the most part, Roosevelt pursued ÔÇ£gentlemenÔÇÖs agreementsÔÇØ with Morgan and other industrialists in order to avoid litigation. The rapport was so warm that many of them contributed to RooseveltÔÇÖs 1904 election campaign. Speaker Cannon remarked, ÔÇ£Roosevelt, business found, had a bark that was considerably worse than his bite, although often his bark was annoying enough.ÔÇØ

After winning a popular mandate for a second term, Roosevelt finally started to push for more ambitious reforms, including a railroad bill to rectify the Elkins Act. In BurnsÔÇÖs program, a locomotive huffs in the background as the narrator boasts, ÔÇ£Now, over the furious objections of the railroads and the powerful Republican senators they controlled, Roosevelt won passage of the Hepburn Act.ÔÇØ

Not exactly. Roosevelt tried to pass a more comprehensive railroad bill, but after encountering opposition, he struck a deal with conservative leaders. When he proudly announced the compromise to the press, one dumbstruck journalist exclaimed, ÔÇ£But, Mr. President, what we want to know is why you surrendered.ÔÇØ A disappointed Democrat grumbled, ÔÇ£I love a brave man, I love a fighter, and the president of the United States is both on occasion, but he can yield with as much alacrity as any man who ever went to battle.ÔÇØ

One of RooseveltÔÇÖs greatest achievements is the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906. BurnsÔÇÖs documentary describes how he subdued recalcitrant congressmen by publicizing the findings of a meatpacking investigation. In fact, RooseveltÔÇÖs investigation aroused little public outrage after the shock of Upton SinclairÔÇÖs novel The Jungle, which Burns does not even mention. Congressional opponents responded defiantly until Speaker Cannon, hoping to heal Republican divisions, visited Roosevelt at the White House and hashed out a compromise.

Despite RooseveltÔÇÖs capable leadership and immense popularity, the conservative power structure remained intact when he left office in 1908. Before departing on vacation in Africa and Europe, he advised his handpicked successor, William Taft, to cooperate with Aldrich and Cannon in order to get things done.

Taft lacked RooseveltÔÇÖs magnetism, however. As he pursued a policy of ÔÇ£harmonyÔÇØ with Republican leaders, the progressive movement exploded across the country, galvanized by economic crisis and driven by politicians far more radical and combative than either president.

When Roosevelt returned after a year and a half, he found the country much changed. Instinctively political, he absorbed the ethos of the moment and transformed himself into the fighting idealist that Burns celebrates. Castigating Taft for cooperating with Aldrich and Cannon, he ran for president as the head of a new progressive party, popularly known as the Bull Moose party.

For one election season, he lived up to the mythology, shaking his fist at cheering throngs as he assailed corporate power and vowed to revolutionize the country. ÔÇ£We stand at Armageddon!ÔÇØ he roared.

But it was too late. Democrat Woodrow Wilson won the day and enacted the ambitious reforms that Roosevelt had failed to achieve ÔÇö federal income taxes, workersÔÇÖ rights, anti-trust legislation, election reform, banking regulation, and womenÔÇÖs suffrage. It would be Wilson, not Roosevelt, who ushered in the progressive policies and institutions that define modern America.

RooseveltÔÇÖs legacy is undeniable. He redefined the presidency, popularized progressive ideas, and achieved some notable reforms, particularly in environmental conservation. He was a great man and an iconic president, but the adulation of his warlike legend is misplaced. Ken BurnsÔÇÖs unquestioning embrace of the Roosevelt myth makes for a great television but poor history.

Michael Wolraich is the author of Unreasonable Men: Theodore Roosevelt and the Republican Rebels Who Created Progressive Politics (Palgrave Macmillan, July 2014).