This review originally ran on Friday, September 12, 2014, but we’re still catching up on DVR — maybe you are, too!

It took quite a long time for me to come around to the idea that Ken Burns is a master filmmaker; that’s probably because his documentaries are driven mainly by voice-over narration, photos, and talking-head interviews, all of which we’re conditioned to think of as un-cinematic (and that, in lazy hands, often are). But if you instead think of Burns as a minimalist — somebody who, at this point in his career, could make any sort of nonfiction film he wanted, but who continues to make films the Ken Burns way — you start to understand how supple and expressive and unobtrusive his technique is, and how much emotional power he summons from the handful of filmmaking tools he’s permitted himself. Less truly is more with Burns — though of course, considering his running times, he often gives us too much of less is more.

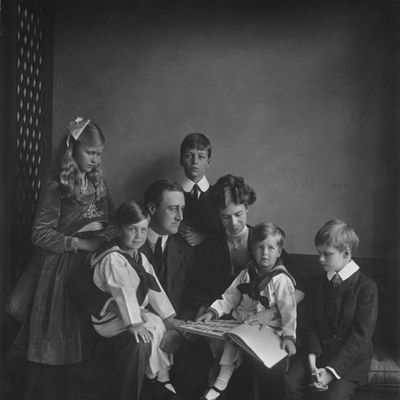

That’s definitely the case with The Roosevelts, his new seven-part PBS series that debuts Sunday at eight and continues in that same time slot throughout the week. It’s being sold as a portrait of the three most famous and influential members of one of the United States’ most prominent families — Teddy, Franklin, and Eleanor Roosevelt — and it is that, up to a point. The early chapters focusing on Teddy are a joy because Teddy’s brutish magnetism is the dramatic equivalent of a gravitational field drawing everything else tightly around it. He was easily ten times larger than the turbulent era that he stalked through, blustering and fighting and remaking the political landscape to match his values. Burns makes the most of Teddy’s tall-tale charisma, corroborating marvelous narrated details with just the right photograph, and often zooming in to pick out a detail that makes us laugh through its sheer rightness (such as the tightly closed fists on display in nearly every seated portrait of the man). He was the first president to ride in a submarine, send a trans-Atlantic cable, own a car, win the Nobel Peace Prize and invite an African-American to dine at the White House. He was also one of the few (FDR was another) who both believed that government’s main job was to defend the general population against economic and legal injustices perpetrated by wealthy individuals and corporations, invoking the Sherman Antitrust Act against 40 trusts, more than his three White House predecessors combined.

A few moments in the Teddy chapters made me wish I’d seen at least the first couple of chapters with an audience, to hear their laughter and applause — particularly the account of Teddy’s 1912 survival of an assassination attempt during a speech; he peeled off his coat, showed the audience his bloody shirt, held up his bloodstained speech, then tore it up and spoke extemporaneously for an hour before being taken to a hospital. It’s easy to imagine Burns turning in a Teddy-centric two- or three-hour film that thoroughly illuminated the man and his era.

The Roosevelts goes much further, though — and unfortunately it loses focus and momentum during its travels. Teddy was born in 1858; this series covers the next hundred years of American and world history while simultaneously trying to place the Roosevelts in political context and analyze their complex psychologies. It’s a miscalculation; sometimes Franklin and Eleanor (and Teddy, to a lesser extent) get overwhelmed by everything else, and there are long stretches during the fifth, sixth, and seventh installments, which cover the Depression and World War II, when it seems as though the series might have been more accurately titled The Times in Which the Roosevelts Lived. The accounts of the origins, complications, and endings of the two World Wars are reasonably engrossing, but The Roosevelts isn’t casting new light on anything it shows us — a lot of this material is covered every week on the History Channel, though admittedly with less elegance, and some of it has been covered by Burns himself. The Depression sequences aren’t as finely judged and affecting as similar material in Burns’s late masterpiece The Dust Bowl, which aired just two years ago and might still be fresh in viewers’ minds. Even when the historical overviews hold your attention, you’re aware that you’ve been to this time or that place before, perhaps with Burns as your guide, and that in revisiting that time and place again here, often in greater detail than was necessary, he allows his title characters to recede too deeply into the fabric of the series that bears their last name.

It should still be said, however, that pretty good Burns is pretty great, provided you more or less agree with his take on things (as I do). Where real history is concerned, Burns is as much of a cinematic mythmaker as John Ford, Steven Spielberg, or Oliver Stone. You’re aware that what you’re seeing isn’t a just-the-facts recitation of what happened and to whom, but one filmmaker’s presentation of a particular political worldview (mainstream liberal, optimistic verging on rosy, but hypersensitive to issues of race, class and gender that other big-ticket documentaries tend to gloss over). This is an example of an artist using the past commenting on the present without being too obvious about it. The parallels between the civil rights and anti-lynching initiatives of the 40s (Eleanor was apparently much more adventurous in venturing to the right side of history than Teddy or Franklin) and the racial unrest of today don’t need to be spelled out, because the series assumes you’re going to be thinking about them anyway. Ditto Eleanor’s struggle to carve out a room of her own, as it were, in the testosterone-soaked atmosphere of Washington, without causing her paralyzed husband, who was sometimes described as a “mollycoddled” rich kid, to seem unmanly in the eyes of less evolved Americans.

Eleanor’s spiky determination rouses the series’ energy during the second half. Among other assertive acts, she pushed her skittish husband to get behind a law outlawing discrimination in government jobs, visited historically black colleges and let herself be photographed with the students, and didn’t try to hide the fact that she found segregation both morally offensive and fundamentally dumb. In the 1940s, when a Birmingham policeman told her that she couldn’t sit among African-Americans at a segregated meeting, she moved her chair between the black and white sections “to demonstrate the absurdity of the situation.”

She was also, apparently, as much an iron woman as Teddy and Franklin were iron men. During 1940 alone, Eleanor entertained 323 overnight guests, oversaw dinner for 4,729 more visitors, presided over 9,000 tea-time guests, shook hands with another 14,000 visitors, delivered 45 lectures, dictated a daily column, and conducted a weekly radio program. Just reading that list makes me need a vacation.

Sensitively written by historian Geoffrey C. Ward, who also appears as an onscreen commentator, and narrated by Peter Coyote (in one of the finest voice-over acting jobs I’ve ever heard, and I’ve heard quite a few), The Roosevelts showcases Burns at what might be his peak as a director. Even when the storytelling architecture falters, his eye and ear rarely do. He starts and ends pans and zooms across photographs with an unerring sense of rhythm, so that a key face, building or object appears a split second after you’ve heard the narrator (or a guest actor reading a quote by a historical figure) say something that puts the next image in a surprising or delightfully inevitable new context.

When the narration, for instance, describes how “the party machine tried to control what did and did not happen on Capitol Hill” during Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency, it’s matched with a shot of an anonymous man in a black coat and bowler seen from behind and partly obscured by a marble column, almost a 1970s paranoid thriller image. When Henry James is heard describing Teddy as “the monstrous embodiment of unprecedented and disastrous noise,” it’s matched with a picture of the smugly grinning president with his arms held aloft in a faintly Nixonian V shape. During an account of a college reunion party held on a family yacht, a classmate of Franklin Delano Roosevelt recalls that “he had that characteristic way of throwing his head back and saying, ‘How are you, Jack?’”; the line is matched to a slow vertical pan that starts on the deck of the boat and travels up a young, standing FDR’s nattily suited figure, ending on a confidently grinning face tilted back just so. Burns has won a lot of awards, but if you watch his work closely — even imperfect and overreaching work like The Roosevelts — you may conclude that, in a way, we’re still underestimating him. He’s a quiet magician.