There’s never been a comics character like John Constantine, DC Comics’ trench-coat-sporting magician and wisecracking righter of wrongs. He’s openly, specifically political. He’s queer. He’s working-class. He’s wordy. He’s indelibly and un-stereotypically English. Astoundingly, he’s remained largely unchanged since he first took to the page in 1985 and throughout 26 years of constant publication — a kind of character consistency that’s unheard of even among icons like Superman or Batman.

And there’s also the matter of how often he appears before his writers. Like, literally shows up out of nowhere on an otherwise ordinary day. Flesh and blood, cigarette and tie. They swear to it.

Jamie Delano ran into him during a stroll near the British Museum, back when he was writing the first few arcs on Constantine’s solo series, Hellblazer. “The figure caught my eye and cocked his head, flicked the ash from a ciggie, and continued without stopping,” Delano told me. “For a few moments I considered following but thought better of it. I mean, what the fuck would I say? And what trouble might one get into?” Peter Milligan saw Constantine at a party around 2009 and rushed after him, only to find he’d disappeared. Brian Azzarello saw him at a Chicago bar in the early aughts but avoided him. “The thing is about John is, the last thing you’d want to be is his friend,” he told me.

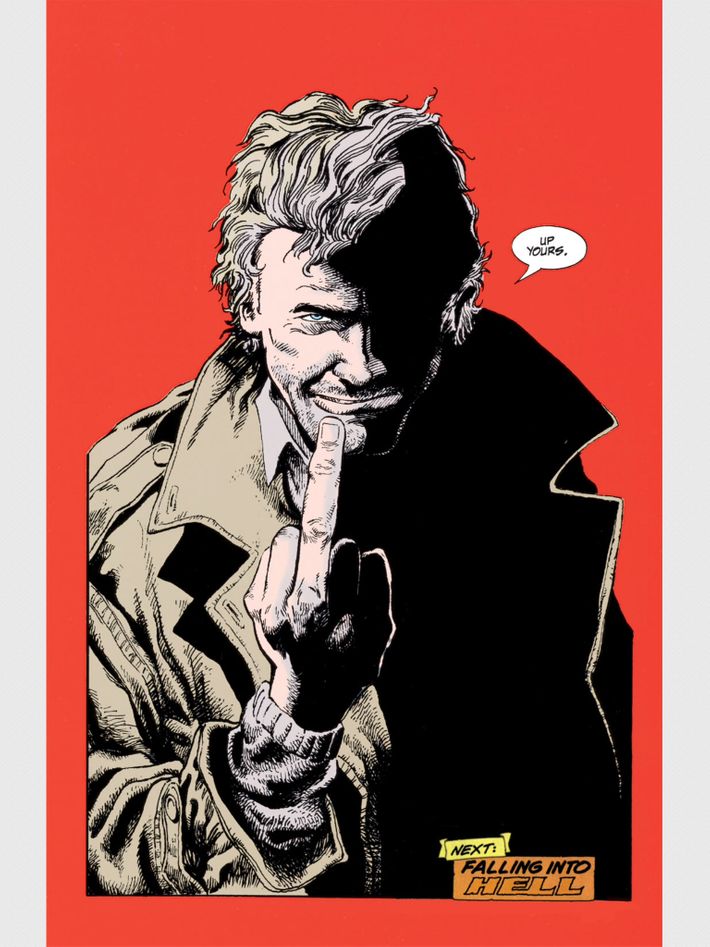

As far as I’ve been able to deduce, Constantine’s only ever spoken to one writer: the man who created him, Alan Moore. According to Moore, he ran into John years after he’d stopped writing him, and the wisecracking mage whispered 13 words to him: “I’ll tell you the ultimate secret of magic. Any cunt could do it.”

Of course, it’s unlikely that a fictional character literally manifested himself in the real world (though one never knows, of course). But even if all of these incidents were just subconsciousness-driven visions the writers had, that’s remarkable in and of itself — you never hear about comics writers having mass hallucinations about Spider-Man, after all. Once again, Constantine stands alone.

And today, this beloved piece of intellectual property stands at a crossroads: his 30-year legacy is at risk. With the TV series Constantine, DC wants Constantine to be a household name — and that might be the worst thing that ever happened to him. Here, then, is the secret history of John Constantine, and a glimpse of dangerous things to come.

****

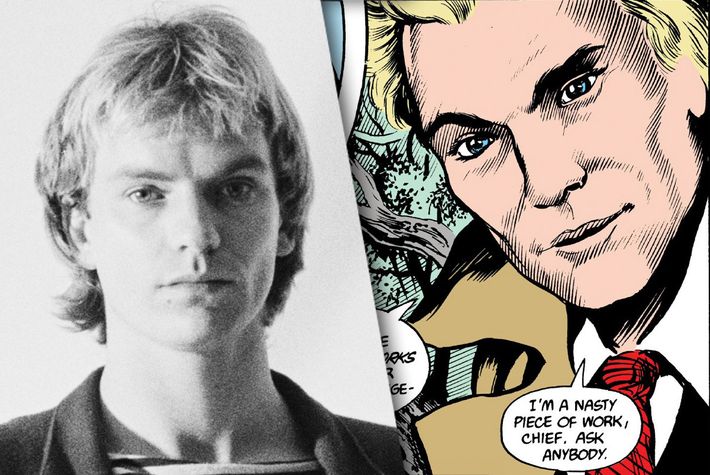

Constantine’s real-life origin is as arbitrary and silly as the character is constant and dour. The major players in his creation give slightly different accounts of the specifics, but everyone agrees on one thing: He was supposed to be like Sting for some damn reason.

He first appeared in the pages of the supernatural comic Saga of the Swamp Thing in June 1984, just after the end of the Police’s world tour for their megahit LP Synchronicity. At the time, Swamp Thing was helmed by British writer Alan Moore, who was two years away from becoming a comics superstar for writing Watchmen. But as of ‘84, he was still a relatively obscure British scribe, gaining cult success for his deconstructionist and mystical take on Swampy. At his side were American artists Stephen Bissette and John Totleben. All of them were obsessed with Sting.

Bissette claims he asked Moore to let him create a character that looked like Sting. The series’ editor, Karen Berger, told me it was Totleben, who had been wowed by Sting’s portrayal of a possibly demonic con-man in the 1982 film Brimstone and Treacle. Moore told The Comics Journal that he granted the artists’ wishes just for the hell of it. And so a nameless Sting-esque character popped up in a crowd shot in Swamp Thing No. 25. That could’ve been the end of it.

But Moore saw the potential for “something more than that.” Moore had been mentally toying with the traditions of English mysticism (though he was still a few years away from identifying as a practitioner of magic). But he was also fascinated by cartoonist Eddie Campbell’s character Dapper John, an archetypal English “wide boy” — a man who takes unreasonable chances and gets by through resourcefulness and smooth talk. He decided to do something previously undone: craft a wide-boy mage.

In June of 1985, within the pages of Swamp Thing No. 37, Moore introduced readers to the first full appearance of John Constantine. It’s remarkable how much of Constantine’s core traits were right there in his first issue. He keeps dropping in on people unexpectedly — a nun, an addict, Swamp Thing — clad in his beige trench coat and wearing a knowing smile. His girlfriend is visited by a kind of demon and commits suicide, setting up a running (and problematic) motif for John: The women in his life are always in danger. And right away, we get his trademark silver tongue and con-man’s talent for the baited phrase.

“And since for the next four days you’re going to be about as dangerous as a turnip, there’s not much you can do about it,” he tells Swamp Thing. who, at the time, was only partially regrown after a battle. “My name’s John Constantine, and I think we could do each other a favor. Mind if I smoke?”

“How … could you … help me?” Swampy asks as John lights up.

“Because I know who you are, mate …” John replies, pausing to let his words sink in. “And you don’t.”

For the next few dozen issues, John was a central character in the weird world of Swamp Thing, becoming a sort of chain-smoking Yoda to the moss-covered behemoth. He revealed to Swampy that he wasn’t just a monster but instead the latest manifestation of a mystic, elemental force. He took him to places he’d never been, from the Justice League’s orbital watchtower to the hidden Parliament of Trees, where plants met to debate the fate of the world.

Readers were enchanted. “There was a great buzz about Constantine,” Berger said, recalling the letters she’d receive from fans. “Alan very deftly planned him as this character who kind of drifted in and drifted out, leaving clues for something ominous and impending.” Which is, of course, the core of what keeps readers of superhero comics coming back to any given series.

Nearly all the subsequent Constantine writers I spoke to remembered how those Swamp Thing issues gripped them — especially because he gave so little away about his origins or what he knew. “You know that quotation from Moby-Dick, ‘It is the easiest thing in the world for a man to look as if he had a great secret in him’?” writer Mike Carey said. “That’s how Constantine was in Swamp Thing.”

It became obvious to Berger that the time was ripe for a Constantine solo series, and she had no shortage of fire-brained young Brits who wanted to take the helm. A young Neil Gaiman tried to pitch her on a Constantine monthly, but it was too late: Moore had handpicked Jamie Delano as his successor. Delano was an unknown to Americans, having made his bones writing for the U.K.’s acclaimed sci-fi series 2000 AD. But he immediately impressed Berger with his explosion of ideas for John.

“He basically gave me — and it’s one of the few things I’ve saved over the years — his original proposal for [the series], and it had everything: John’s personal history, his ancestors,” Berger recalled. “He really didn’t need any direction in terms of a mandate from me.”

They had a killer idea for a title: Hellraiser. Of course, in a perfect bit of timing, Clive Barker’s movie Hellraiser was announced just as Berger and Delano were developing the series.

“I remember coming up with a random list of alternatives, Hell-bent being the one I favored,” Delano recalled. Neither he nor Berger could remember who came up with Hellblazer, but Berger loved it. Delano, not so much. “I kept flashing on devils wearing sports club jackets, but once it was done, I quickly became accustomed.”

And so, in January of 1988, Hellblazer No. 1 hit stands. Readers who picked it up couldn’t have predicted how ambitious, political, terrifying, long-running, and cultishly beloved the series was about to become.

****

If Moore’s John Constantine had been built on hints and shrewd withholding of information, Delano’s was built on an abrupt shift to rich and detailed mythmaking. His 40-issue run on the series was one of those rare outbursts of creativity in a monthly comic, in which nearly every issue introduced a character or plot development that became fundamental for subsequent writers and readers of the character (in this respect, its closest analogue might be Chris Claremont and John Byrne’s run on Uncanny X-Men from a decade prior).

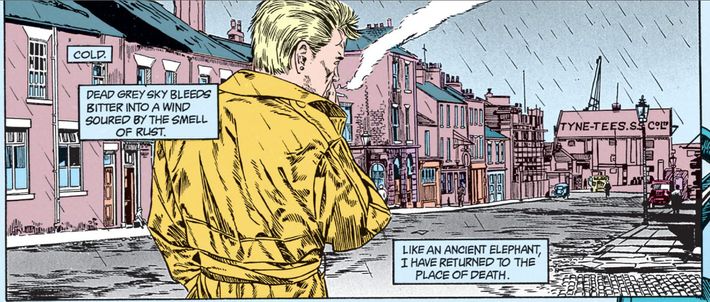

Readers learned about Constantine ancestors dating back to the sixth century, AD. They heard about John’s upbringing far north of his London flat, in the grinding poverty of Liverpool. They found out a fetal John had strangled his twin brother in the womb and that his mother had died in childbirth, leading to constant blame from his drunk of a father. They saw his days in a moderately successful ‘70s punk outfit, Mucous Membrane. They learned about the Newcastle incident of 1978, wherein he and some other young magic dabblers had tried to exorcise a young girl but John’s flashy impatience accidentally led the girl to lose her soul. They saw the aftermath, when he had a breakdown and was confined to a facility called Ravenscar. They met individuals who haunted him for decades afterward: friends like the affable and hapless cab-driver Chas, and foes like the demon Nergal.

Readers also got heaping helpings of Hellblazer’s most distinctive textual trait: the John Constantine narration box. With two notable exceptions (which we’ll get into in a moment), Hellblazer was usually crammed with John’s internal monologues, which drifted in and out of the plot at hand, making stops to ruminate on London, fate, guilt, and everything else you’d expect a moody magician to find important. The prose was always a bit on the purple side, sometimes reading like a low-rent attempt at a ‘30s detective novel. But it became central to the character.

It’s hard to find a better example than this bit of rumination John has in Hellblazer No. 10, while taking a walk after his old pal Swamp Thing mentioned the Newcastle incident:

Remember Newcastle. I do. It fills my mind from Louisiana to London. And all the while I wade through scuttling humanity — flotsam and jetsam, unconscious of the cosmic forces that wash them to and fro. Am I insane to care what happens to these stupid sheep? Is it some psychotic arrogance that drives me to save my species from itself? Is it an impulse of self-destruction that leads me to conjure demons and oppose them? Or is it rage? Remember Newcastle, he said, and slapped me with a sudden chill of anger which now grows tentacles through me, like cancer, or death. Remember Newcastle. I wouldn’t have given him credit for such subtlety — but these two words touch me as precisely as a dentist’s steel probing the exposed pulp of a molar nerve. But who knows what refinements a torturer might bring to his art when he’s had eternity to practice.

Deep breath there, John (and Jamie).

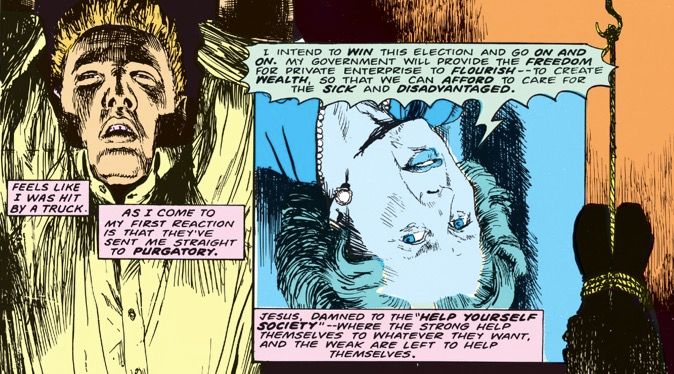

Delano also introduced an unprecedentedly specific and biting dose of political rhetoric into his run on Hellblazer, and he wasted no time in doing so. The third issue of the series features John walking past a billboard where a poster of Margaret Thatcher has been vandalized to give her vampiric teeth and an anti-smoking slogan has been modified to read “VOTING TORY CAN DAMAGE YOUR HEALTH.” The whole issue was devoted to an admirably direct (though somewhat ham-fisted) attack on Britain’s Conservative government, with demons running the show in the 1987 U.K. general election. Subsequently, he packed the rest of his run with digs at the Tories and Britain’s descent into a deregulated hellscape.

“Writing was my (tiny and ineffectual) opportunity to sprinkle the odd grain of dirt into the seemingly unstoppable machine,” Delano wrote to me in an email. “The 21st century is, of course, testament to the ultimate futility of this grit-sprinkling tactic, but it seemed the best course at the time.”

Put simply, no mainstream comic had ever tried anything like this before. Sure, there would be veiled allusions to politics, like the time Captain America found out a nameless Nixon analogue had secretly betrayed America by joining a shadowy cult. But it was always done with vagaries and watered-down, kid-friendly versions of liberal politics. Not so with Delano. Nor, for that matter, with Neil Gaiman, who guest-wrote a stand-alone story about the homeless of Thatcher’s Britain for issue 27. That may have been Gaiman’s only stab at Hellblazer, but he never let go of the Constantine addiction that drove him to pitch that solo series years earlier.

Indeed, if you’ve ever read a story with John Constantine in it, it’s likely thanks to Neil Gaiman placing him prominently in early Sandman tales. In that series, he even introduced a crafty Constantine ancestor named Johanna Constantine, who ran secret missions along the cobblestones of Revolution-era Paris. Gaiman threw the Constantine myth in the other temporal direction, too: In a 1990 miniseries called The Books of Magic, Gaiman foretold the end of the universe, when one of the last beings alive would be some far-future version of John. The character was irrevocably woven into the DC Comics imagination.

Delano left Hellblazer in 1991, shortly after Margaret Thatcher was forced from office. After that, the series pushed the envelope further and further — until DC itself couldn’t tolerate where John was going.

****

In a way, it was only a matter of time before DC ran into trouble, because not long after Delano left, they let John off his leash. In 1993, the company launched its industry-changing Vertigo line of comics, and Hellblazer was one of its flagship titles. Vertigo books were removed from the actions of the rest of the DC universe, and more important, they were free of censorship. Nudity, chilling gore, and hard-core language were all on the table.

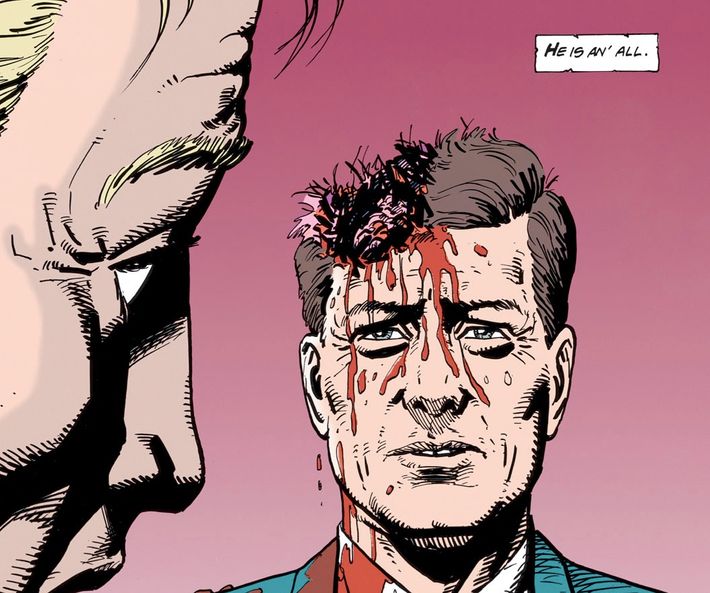

For a few years, things got a little gross in Constantine’s world, but the situation was editorially under control. Northern Irish writer Garth Ennis was Delano’s successor, and his take on the book was more blunt and bloody. He kicked his run off with a story line that was lifted for the 2005 movie Constantine and will be mined in future episodes of the upcoming Constantine show: “Dangerous Habits,” in which John gets cancer and survives thanks to a folktale-worthy swindle of three demons. He had John kick the shit out of National Front racists and travel a murder-filled alternate-reality America with the talking, bloodied corpse of JFK.

Ennis, in fact, is the only one of Constantine’s writers to openly repudiate the character. But it’s not because he feels squeamish about what he wrote — it’s because he’s come to find John morally loathsome.

“I’ve known a few too many lovable rogue/wide-boy types in real life to find the notion attractive, people who abuse their friends, disappear for a while, then come back and do it again because they know they’ll be forgiven,” he told me. “I’ve no desire to write a character who essentially gets his pals killed and then explains that they were doomed anyway, so why not just spend their lives and use them up.”

That distaste didn’t translate to the page, luckily for DC, and Ennis’s successor, Paul Jenkins, wrote the character enthusiastically for four years. The great Constantine editorial train-wreck came, oddly enough, under a writer who only penned 11 issues of the series.

Warren Ellis was, in many ways, hands down the most ideal choice to take over Hellblazer when DC brought him on in 1999. Like John, Ellis was born far from London and soaked it up later in life. He’s deeply progressive in his politics. He had a decorated history of writing tortured loners who alternately attract and alienate everyone around them. At the time, he was one of the hippest writers in comics. And he had thought a lot about John.

“I always conceived of John as being an archetype of British fiction and the British culture of the weird,” Ellis told me, placing him in the tradition of British “occult investigator” heroes like William Hope Hodgson’s Thomas Carnacki. “Our trickster gods are always more sinister, sadder, and doomed.”

Ellis made the book more political than it’d been in years. He launched his run with a six-part story called “Haunted,” in which a grisly murder leads John to reckon with the inherent misogyny of the way he leads his girlfriends into danger. But the most indelible passages were the ones where John gave Ellis a voice to rail against Tony Blair’s New Labour dystopia, where Thatcherism was repackaged with a human face and sold alongside Princess Di memorabilia. Ellis was out to convince the reader that something was deeply wrong with the English-speaking world at the close of the 20th century.

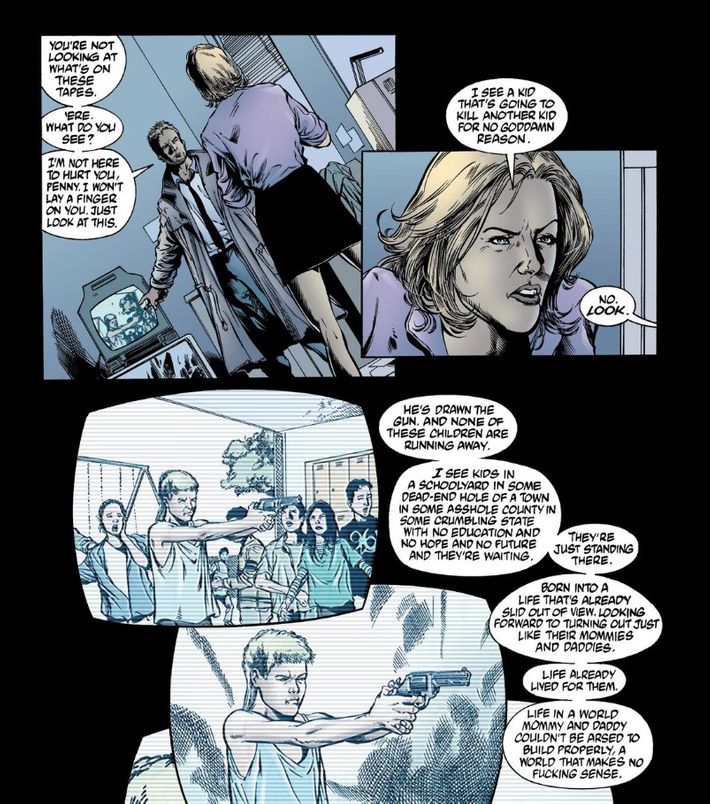

That outlook led him to write the most controversial Constantine story of all time: “Shoot.” It was an astoundingly bleak tale about school shootings in the United States, written just before Columbine but slated to publish a few months afterward, in the waning days of 1999. In it, John witnesses multiple school shootings and concludes that the shooters and their victims are victims of social, political, and cultural forces that have hollowed them out.

“They’re only kids, for Christ’s sake,” John yells. “This is the best response they can manage to the insane fucking world they’re in. They stand there and wait for the bullet.”

The Vertigo team was so passionate about it that it prepared photocopies of the story to send to media outlets for maximum visibility. That’s when DC executive Paul Levitz found out about the story. Levitz refused to publish the story as it had been written.

Berger, at the time the head of Vertigo, wanted the story to run but felt it was out of her hands. Ellis says a couple of weeks of “negotiation and argument and shouting followed, at the end of which I told them that they could either publish it as is or publish it with their required changes and take my name off it,” but no matter what they chose to do, he had no desire to write John Constantine under that regime. He handed in his resignation. A copy of the unprinted issue leaked and the nascent online comics community rallied to Ellis’s defense, but it was too late.

But, surprisingly, Ellis wasn’t done with John. The next year, he published a single-issue story in his own Planetary series at WildStorm Comics. Titled “To Be in England, in the Summertime,” it took the form of a memorial for a thinly veiled Constantine analogue named Jack Carter. Two of the series protagonists knew him, and they fight over whether Jack/John was “funny and smart and mysterious and sexy and scary” or just “a con man who pulled a scam once too often.” All of the weird British heroes of ‘80s comics — many of them Moore and Gaiman creations — attend his funeral. Of course, it turns out Jack pulled a fast one and reappears at the end of the comic without his coat or hair and tosses away his cigarettes. “Time to move on,” he says. “Time to be someone else.”

Oddly enough, DC seemed to agree in its own way, taking a sharp left turn in Hellblazer. For the first time, they hired an American to pen John’s adventures: Chicagoan Brian Azzarello, best known for writing hard-boiled crime comics. For one thing, Azzarello got rid of the famous Constantine narration boxes, leaving the reader to do as much guesswork about John’s plans as the people around him.

But what’s most memorable is the sex and violence. It’s breathtaking to see how gruesome and sexual the series became during Azzarello’s years on the book. John spent the entire time in America, starting off as the center of a prison race war while serving time for a murder he didn’t commit. After leaving, he found himself confronting (and performing on camera with) a ring of black-market pornographers and getting stuck in a town run by ultrareligious white supremacists.

In that neo-Nazi story line, Constantine ran into censorship problems once again. “There was resistance,” Azzarello told me. “It wasn’t the actual white-supremacist belief systems, it was some of their comments about God.” But Azzarello’s biggest legacy was in the story line that followed, where he made John explicitly bisexual. In a guest-written 1992 issue, there had been a tossed-off line about John having “the odd boyfriend” in his life, but Azzarello literally showed him having sex with a thinly veiled Bruce Wayne analogue. That decision would come back to haunt DC years later.

The book’s years of controversy ended with the hiring of Brit Mike Carey in 2002. What followed was years of peaceful renaissance for Delano’s vision of the character. The narration boxes were back, the action returned to England, and although Hellblazer wasn’t controversial, it was critically beloved. Under Carey and his successor, Peter Milligan, John started to show his age in a very literal way. Since the beginning of Hellblazer, Vertigo had allowed John to age in real time — something never done before or since to a long-lasting mainstream comics character. But while writing John in his mid-to-late-50s, Carey and Milligan showed John getting slower, more regretful, and constantly seeing youthful decisions coming back to haunt him.

With age comes mortality. In 2012, around John’s 59th birthday, Milligan got word from DC editorial: It was time for Hellblazer to die. DC had other plans for the character and needed Vertigo’s longest-running series to shuffle off. Milligan allowed John to get married, die, escape death, and ultimately have one of the more fascinating final issues of any iconic comics series.

“I didn’t want to end on Constantine smiling and saying, ‘That’s it, chums, see you in another life,’” Milligan told me. “I didn’t want that easy, obvious out.”

Instead, he gave readers a profoundly ambiguous and unsettling farewell. After a wild adventure, we see John visit his niece, Gemma, who has long suffered the consequences of being around him and has grown to hate what he’s done to her life. He calmly invites her to shoot him with a supernatural gun that will erase him from the Earth. “Damn you, John Constantine,” she says, firing it. The next panel is all black. Then Gemma opens her eyes with a look of shock and speaks the series’ final word: “Uncle?”

The final three pages are wordless. The reader is all of a sudden flying upward, out of London, zooming north into Liverpool. A cat hisses. A woman on a street seems to look at the reader in confusion. We fly into a pub. And there, standing at the bar, is a wrinkled man in a hat, sweater, and coat, staring at us with sunken eyes and gritted teeth, looking haunted and frightened.

Readers have assumed the figure is some kind of future Constantine. Milligan is cagey. “Is it? Or maybe it isn’t?” he told me with a laugh. “For so long, we’ve had Constantine’s narrative voice saying what he was feeling. I wanted, at the end, for that voice to recede and be quiet. So at the end, the reader, who’d come along for so many years, claims the comic. It’s the reader’s voice asking what’s going on.”

But whether or not John Constantine had died at the age of 60 was, in a way, a moot point. From a business perspective, John was far from dead. In a way, Hellblazer had died so that John Constantine might live. After years of confinement to the Vertigo universe, DC wanted a new version of John to step into the big leagues. It was time for John to start hanging out with Superman and solving mysteries on network television. The question is: Will he be able to survive with his soul intact?

****

In 2011, DC introduced a version of John Constantine into the mainstream DC universe, where Batman prowls on rooftops and Wonder Woman swings her lasso. Since the dawn of Vertigo, John’s adventures had been explicitly removed from the superhero universe. But 2011 was a year of upheaval for DC, in which it tried to consolidate all its intellectual properties into one shared universe. A 30-something John Constantine, looking and speaking much as he always had (minus the swear words), popped up to chase after Swamp Thing. Within a few months, John was swept up in a massive DC overhaul called the New 52, in which every DC title was rebooted with a new No. 1 issue and all previous character history was erased and rewritten. John had a new lease on life.

But, confusingly, Hellblazer ran on for two more years, completely separate from those superhero stories. Milligan wrote John’s first New 52 appearances in a mystical series called Justice League Dark, meaning he had two John Constantines hopping around in his head until Vertigo Constantine disappeared forever in 2013. And Milligan isn’t shy about saying which John he prefers.

“When [New 52 Constantine] became the only incarnation of this character, he just becomes some British geezer that does some magic,” Milligan said.

He’s not alone in his disappointment. “They’ve taken the character and put him in a place that’s Constantine-lite,” said Karen Berger, who left DC last year. “As far as I’m concerned, he’s not the real Constantine.” Delano said he’s avoided reading the new stories.

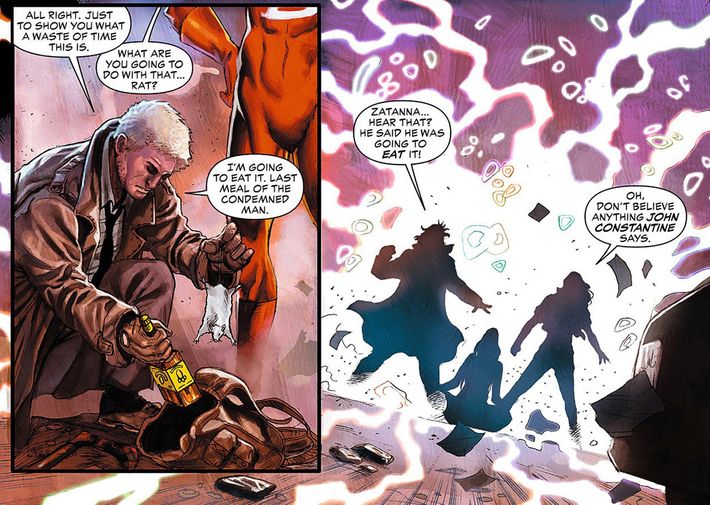

Justice League Dark has garnered some critical acclaim and is perpetually rumored to be in development as a movie directed by Guillermo del Toro. But John’s new solo title in the New 52, Constantine, has been met with critical disappointment. The stories aren’t disrespectful or embarrassing, but John has become something of a supernatural James Bond, jetting from location to location with a grin and a trick, rarely pausing for the interpersonal drama that filled the pages of Hellblazer. He’s also become something of a superhero: He fights giant monsters and magic tricks often look like the typical power rays and lightning bolts of DC lore.

There’s hope for the John of the comics. Constantine’s current writer, American Ray Fawkes, is a devoted student of the character who’s been reading him since his first appearances in Saga of the Swamp Thing. “When I write the stories, to me, in my mind, they’re Hellblazer stories,” Fawkes told me. “There’s something really appealing about being the guy who’s willing to make the sacrifices nobody else is, to get the job done.”

But of course, actual comics aren’t where anyone measures the real success of comics properties these days — the screen is where the money and the notoriety are. Alongside The Flash and Gotham, DC is pushing the launch of NBC’s primetime Constantine series as a crown jewel of its TV efforts.

Of course, this isn’t the first time an actor has stepped into John. In 2005, DC parent company Warner Bros. made a feature film called Constantine, starring Keanu Reeves as a barely recognizable version of the character. He was an American, his wisecracks were barely there, and his sidekick Chas was played by a young Shia LaBeouf, of all people. The movie was a box-office success but a critical bomb and quickly left the popular imagination. (Its most important legacy is as the feature-film debut of current Hunger Games series director Francis Lawrence.)

This time, DC has much more creative control, and it’s sticking to what it thinks makes John great. It’s far too early to tell whether the show will capture the energy that has driven John’s astoundingly long — and still uninterrupted — comics career. The first episode puts John in the position of saving a young American woman who’s beset by evil spirits, then taking his new companion on a wild journey through magic, like a supernatural Doctor Who.

The show’s promotional tour got off to a very bad start among progressive comics fans. A few months ago, some poorly chosen words from the show’s creators led to the belief that the TV version of John wouldn’t smoke and — even more controversially — wouldn’t be bisexual. As it turns out, he will smoke within the limits of network TV, and the creators assure me they’re leaving the door open for some kind of queerness in the future. But not everyone has gotten the message, and skepticism among John’s fans is still running high. If the show succeeds enough to last, fans should know they have an ally in the form of showrunner Daniel Cerone. Formerly the showrunner for Dexter, Cerone has been reading John’s adventures all the way back to Swamp Thing and is passionate about capturing John’s essence.

But if there is hope for Constantine, it lies in the man in the trench coat: Welsh actor Matt Ryan. Cerone told me about Ryan’s audition tape, recorded while he was finishing up a stint in a West End production of Henry V, which required him to grow his hair out and sport a massive beard. Cerone said he knew instantly that Ryan was their John, as un-John-like as he looked, because he had “the eyes and the elocution” of Vertigo’s favorite son. “He just — those eyes! You fell into them! You didn’t see anything else but his eyes!”

Cerone has a point. Throughout the otherwise uneven pilot, Ryan looks supremely comfortable and eerily familiar. With any luck, the world of Constantine will rise to meet the man playing Constantine.

But what if the best thing for John would be for the show to fail? He’s thrived for nearly 30 years without ever becoming world-famous, so perhaps the back alleys of culture are where he belongs.

“Superman and Batman are icons and brands, so they’re always having to get changed and rebranded,” Peter Milligan told me. “Constantine gets left alone because he’s this scruffy geezer who does a bit of rubbish magic. If he ever got big, he would have to be changed.”