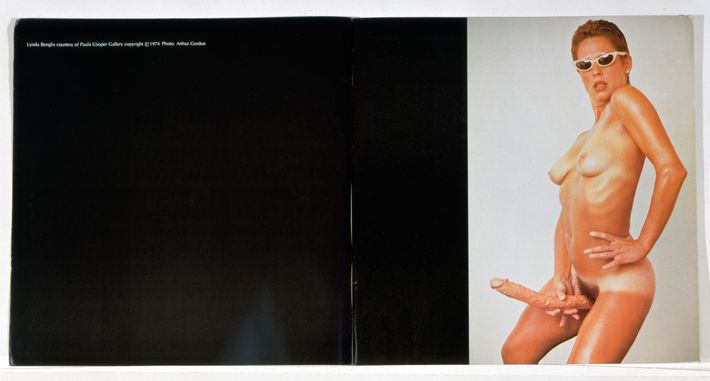

If you are a young or emergent artist working today, there’s a pretty good chance you hadn’t even been born when Lynda Benglis published her infamously naughty ad in Artforum in November 1974. The legendary work turns 40 this month, and we reached out to 26 female artists — some working in 1974, some born since — to ask what they made of it then, what it means to them now, and how, if at all, they thought the state of gender politics in the art world has changed in the years since.

Originally, Benglis wanted the image to accompany an article written about her solo exhibition at Paula Cooper, but then-editor John Coplans refused, allowing only that the photograph appear as a paid advertisement. Several of the associate editors at the time considered the ad pornographic and unsuitable for the art magazine, which eventually resulted in art critics Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson leaving to form their own magazine, October. As a follow-up, the December Artforum of the same year featured a letter written by the aforementioned critics and three of their then-colleagues, lambasting the magazine for publishing the ad, which amazingly still retains the power to shock and startle — a direct and performative declaration for Benglis taking the system dominated by male patriarchy into her own hands, literally. Feminism is still a live wire in the art world, as was seen in the recent “Future Feminism” at the Hole Gallery (among other exhibitions), with many women feeling they are not on equal footing with their male counterparts. The Artforum ad was addressed to that subject exactly; so, how do those women feel about it today?

MARTHA WILSON (b. 1947)

Lynda Benglis’s piece in Artforum rocked my world. When I saw it in 1974, I was living in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, where art magazines were the primary source of current info. WOW! I did not associate the image with the underrepresentation of women in the magazine; rather, I saw it as a woman performing sexuality as a legitimate subject of art and pointing to power as the fundamental conflict between the sexes.

MICKALENE THOMAS (b. 1971)

In regards to my own practice, I would like to think that the women in my work feel as empowered by their posture and gaze as much as Ms. Benglis did in that image in 1974. We’ve come a long way since then but yet it never seems like enough. Thank you, Lynda!

It was more than 20 years after the date it was published that I saw the Benglis image, and I remember saying out loud, “All right, fucking rock on!” Also, a quote by Ayn Rand comes to mind every time I see it: “The question isn’t who is going to let me; it’s who is going to stop me.”

LAUREL NAKADATE (b. 1975)

I first saw the Benglis image during the fall of my freshman year of college, and I saw it as a war cry. I think Benglis should re-perform that image now, 40 years later, because there is still more work to be done.

BETTY TOMPKINS (b. 1945)

I think the same thing now as I did when I first saw the ad 40 years ago: Lynda Benglis has balls!

LOUISE FISHMAN (b. 1939)

I met Lynda Benglis at the Carmine Street pool, where we both swam laps — probably in the early ‘70s. I had first seen her work at Paula Cooper’s gallery on Prince Street — the blob of color in the corner during one early group show.

I knew from the locker-room experience that Lynda was blessed with a gorgeous body and was an exquisite swimmer. I was on Paula’s mailing list, so I got an announcement in an envelope (unusual at the time) of Lynda wearing aviator sunglasses while leaning against a vintage convertible car. She was incredibly good-looking, and I was always interested in what she did (the early video of her and Marilyn Lenkowsky kissing — radical at the time, but not for me as a seasoned and political lesbian from the late ‘60s on.) Paula Cooper was my hero and still is. I admired Lynda’s chutzpah, but also knew she was straight and privileged — unlike me and the movement lesbians who were my allies at the time. When the Artforum photograph came out, I was suitably impressed — with her body, her outrageousness, and her cunning. We need more women like her in the art world.

LATOYA RUBY FRAZIER (b. 1982)

The “Benglis ad,” although important to counter the domineering patriarchy of the ‘70s, bears no witness to me as an artist working post 1974. At first glance I find it humorous, but what it really represents to me personally is social and economic exclusivity and inequality. How many artists can afford to take out a $3,000 advertisement? How many non-white women artists are represented by galleries in New York City?

I am a human being that wants equality for all practicing artists. As an African-American woman from a working-class background, I am aware that my artistic labor and artwork are devalued when compared to male artists as well as white women artists. It is imperative that we look beyond binaries of gender and address the economic disparities that prevent artists of color from fully participating in the arts and feminist discourse.

WENDY WHITE (b. 1971)

As far as the Benglis ad, there are still plenty of penises in Artforum, but they’re way smaller and not as smart. Men still get the lion’s share 40 years after Benglis’s ad because it is still bestowed on them year after year, whether the work deserves it or not. So what can we do? As artists, we have to be supportive of work that we admire regardless of gender. But specifically, as women artists, it is imperative that we draw attention to other women artists as often as men draw attention to other men. WHICH IS ALL THE TIME. Stop believing that we should be happy with the literal crumbs that we get in comparison. Museums, collectors, and galleries all need to quit the risk aversion and quit supporting artists who are risk-averse — because it is our freaking duty as creative people to take risks. What’s as risky now as Benglis was then?

LITA ALBUQUERQUE (b. 1946)

My mother was the embodiment of Lynda Benglis’s infamous Artforum image, which was burned in everyone’s mind 40 years ago. My mother lived that way her entire life and made as strong an imprint in my life. I am not a feminist, per se, as the path had been cleared before me, but I certainly had my share of experiencing being a woman artist in the ‘70s in Southern California when male artists ruled. Though it was an issue socially I never forgot the image of my mother boldly and unapologetically breaking the rules. Even though I did not carry the banner of feminism, I certainly feel that through my work and example as an exhibiting artist that I disseminated this message in a visual format. Through collaboration with architects, scientists, filmmakers, musicians, and artists, I strive to create a relationship of equality that pervades my work.

BETTY WOODMAN (b. 1930)

I think I saw Linda’s ad in Artforum when it was first published. I thought, If I had a body like that, then I, too, could do something similar. But no such luck!

I consider myself a feminist, or it might be more correct to say I did at the time. I was making functional pots to cook in and eat out of, and a woman’s role was in the kitchen. Also, women made work that was much more inventive because of their awareness of possible functions. Nurturing, containment, things being all about the female, and the politicizing of women were all things I lived through from the earliest moments. Lucy Lippard and Marcia Tucker came to Colorado where I was living and we all had our consciousness risen.

RENEE COX (b. 1960)

I loved the Benglis ad, as I think it said, “See me now!!!” She has some big inner balls!!! She made people look.

MARILYN MINTER (b. 1948)

Lynda’s ad in Artforum was/is brilliant! I am always supportive of women owning production of sexual imagery, of women becoming the agents of sexually provocative images instead of always just being the subject. Of course, I consider myself a feminist. Advocating social, political, legal, and economic rights for woman equal to those of men — what idiot would say they don’t advocate this, male or female?

Asking about the next step is a good question to have, especially considering young women using loaded sexual imagery constantly get “slut shamed,” as certainly Lynda was back in 1974. Now that she is an elder the ad is considered groundbreaking and genius. But it seems that women owning the sexual power dynamic is still very threatening today — just look at how Madonna/Miley Cyrus are treated in media. Regarding the art world, I think it’s time for women collectors to start “leaning in.”

DEBORAH BROWN (b. 1955)

I remember seeing the Benglis ad in Artforum when I was a college freshman at Yale, where I was an art major. It made me want to move to New York and be an artist! Seriously, being at a historically all-male college, I thought I had acquired the skills necessary to move to New York and compete in the art world. But from my current perspective, I don’t think it’s necessary to “don the phallus” to be successful as a woman artist in New York. Being an agent of change within a community can be a pathway to success. That, to me, is feminism’s legacy. You don’t have to out-duel your male counterparts. Instead, working together to create a platform that lifts others and boosts your own career at the same time is a better route. For me, an obsession with hierarchy and exclusion is a shortsighted strategy, and if you live by this code it will come back to bite you.

I consider myself to be a feminist. Unlike many artists in my young circle in Bushwick, I am old enough to remember the ‘70s when the women’s movement was just gaining strength, creating community and dismantling the status quo. I have been in the New York art world since the early ‘80s, but things really began to look up for me professionally when I saw myself as an agent of change in my own community in Brooklyn, making opportunities for artists in general and for women artists in particular. The feminist movement has inspired me to take an activist position in my own community to program what I want to see in my artist-run gallery space, Storefront Ten Eyck, outside the commercial art world of Manhattan. This engagement with others has helped me to grow as an artist and as a person, and it’s had the added bonus of raising my profile professionally. I now see myself connected to a broader agenda. Feminism — with its foundation of egalitarianism, non-hierarchical structure, and transparent dialogue — has been, in part, my inspiration. Working together on an equal basis floats all boats, and there is no greater proof of that than the artist-run scene in Bushwick.

KATHE BURKHART (b. 1958)

Regarding the Artforum ad, I think, tongue-in-cheek/chic and site-specific as it is, Benglis portrayed herself as a phallic woman. She’s performing gender, not performing “male.” Phallic women who don’t cleave to the “norms” of a gender binary are still the elephant in the room. It’s still a touchstone image for me, which existed before we had the term gender non-conforming.

The word feminist is parity along with equal representation and acquisitions, a 50/50 balance and closing the wage gap as it relates to pricing. [The proof is] all in the numbers, which makes plain the situation. There is no dearth of talent. Nothing else matters, and progress is slow. And yet, every time a woman sells a work for over $50,000 or her work is acquired by a major collection or shown by a major museum or leading gallery, all women win. It could also be helpful to look at the issues within the larger framework of human and artists’ rights, an undeveloped area. Government support to institutions could create guidelines that may help this along by mandating quotas.

NATALIE FRANK (b. 1980)

The ad continues to jolt. It is iconic. A few waves of feminism later: Benglis’s strap-on reverberates with more humor and less shock. In the 40 years since, culture has absorbed so many transgressed images that this ad feels more a part of the history of feminism. For me it marks a specific time when it still shocked men and woman alike to see a woman perform sexuality and gender with pointed aggression. These days, these [types of] performances often seem implicit — in the art of men, women, and feminists alike. How can performance ever be separated from all aspects of identity? I remember seeing it when I was 12 or 13 and laughing out loud; it still has got me by the balls.

What we need are more critics writing about this disparity (thank you, Jerry); more art historians considering women artists, gender, performance of sexuality, identity in contemporary art (hark to Linda Nochlin!); more dealers bringing in fresh voices (I for one am bored by the bad boys and excited by the thoughtful, perverse, and engaging work of Nicole Eisenman, Dasha Shishkin, Dana Schutz); more women assuming leadership positions (as Dr. Elizabeth Sackler becomes the first female chair of the Brooklyn Museum); plainly, greater representation of women.

DIANA AL-HADID (b. 1981)

We can all agree that Lynda Benglis’s ad was incredibly bold for the time and that she was obviously fearless. She knew that sometimes being polite, or being a “good girl,” is not enough. She was rightly outraged at the dominant belief in female inferiority, and in acting “inappropriately” she exposed a surprising number of people in the presumably progressive art world as narrow-minded and unforgivably conservative. The ad is a reminder now that there’s a tremendous amount of work to be done to give women a bigger presence in the art world (and in all other worlds). There’s always a backlash at the inception of real progress, and we are at that moment again today. It’s a reminder that women need to act like men, to take up more space, to stop being so polite and accommodating when it’s not working, and to wear cool power shades while doing it. She’s still a total badass.

It’s hard to say exactly how it’s affected me. It’s one of those things that obviously paved the way, becoming part of the legacy of the feminist movement in art. All female artists today have to be thankful for her strapping on that dildo, but it’s hard to draw a straight line from that moment to how it’s directly “affected” me or my work in a specific way. It’s just a significant chapter in the opening up of this critical conversation; it made space for women after [publication] to be loud and ask for more.

I consider myself a feminist and, quite frankly, am confused as to how anyone could not relate to the term (whether male or female). I didn’t need to know about the word to know that I was a feminist as a girl, always wanting equal treatment, as any girl does. Regarding my practice, everything I believe in plays a role — how can it not? As I entered college, I wanted to know what the boys seemed to already know; I wanted to know how to weld, how to use tools, and how to take up lots of space and make a mess. I was always sensitive to territorial claims of space and privileged information. I think it’s crucial that women take up more space — more physical space, more social space, more political space. So much of our culture is set up to prevent women from expanding, from being or thinking or acting big. So much [of the system] is set up to prevent girls from being messy and spreading out — everyone likes a “good girl.”

JUDITH BERNSTEIN (b. 1942)

Lynda Benglis did a KNOCKOUT job showing that women can do it alone! Her work, as well as mine, is sexual and political. My strong feminist conviction has both helped and hurt my career, and it’s analogous to Lynda’s double-ended dildo! I’ve wrestled with censorship since 1974, my humongous phallic drawing Horizontal was censored in “Women’s Work - American Art” in Philadelphia the same year as Benglis’s infamous ad. I understand both the negative and positive aspects of notoriety, and I’m thrilled to continue making provocative work. Women are still fighting to get access to the system and are lacking in galleries and museums. I’m confronting this and other struggles using the angry cunt in my current Birth of the Universe paintings to represent the rage of women. My philosophy is DON’T HOLD BACK!

SAM MOYER (b. 1983)

Lynda is a hero of mine. She was one of the first female sculptors I discovered. I remember watching a video of her making one of her bow pieces when I was 19 years old and thinking, She just does it; she lets it [the material] do what it wants, still knowing what she wants it to do. I think I was struck by the ease of her confidence. I later, luckily, had the opportunity for a few studio visits and even worked for her for a minute. No matter the content or context of our conversations, that ease of confidence was present. Her ease is what struck me; it is and was so natural. That is still what I take away from the Artforum ad, the naturalness of it. It works because she is the one doing it, and she lets things do what they will but knows what she wants them to do.

LISA CORINNE DAVIS (b. 1958)

I have a huge relationship to the Benglis ad in Artforum. I moved to NYC in 1978, four years after it had been published. As a female art student, that is all that we talked about. I kept a copy of Artforum open to the ad on my coffee table. I was in awe of the courage it took to make such a bold statement, to be nude in an art magazine. At the same time, I felt Benglis’s vulnerability and her cry to be heard. It has always been an image that has encapsulated the stakes women take when they loudly voice their objections to wrongs that first and foremost affect them.

I was raised by a single mom who was one of the first of three African-American women to get a law degree in the state of Maryland. She is fierce, smart, and independent, and she always insisted that her voice be heard. I began to learn all of these qualities from her as the first wave of feminism advocated for women’s rights. I watched her fight for her rights in a workplace that at the time had virtually no women at upper levels. Her values aligned with the developing women’s movement. Therefore my awareness of feminism was a concept, not a term. As a painter, though I hate to say it, I cannot see the effects of feminism. Men still shockingly dominate the art world, and misogyny runs amok. There seems to be no shock or shame about a massive business that barely gives a nod to women.

JUDITH BRAUN (b. 1947)

I think that the Benglis image is still provocative and holds a very important place in women’s history in the art world. Not that things have changed that much, because a scan of Artforum’s pages will still show a predominance of male artists. But it made a statement in a concise and shocking way that could not be ignored, and I am glad that she had the courage to do it; I am glad it exists. It is a touchstone and reference for a point in time, for historians and for younger generations. If I imagine it out of the picture, it would leave a gaping hole (no pun intended). I do think that it is also dated to that era, because if it was done today it would not be as shocking and could be read on many other levels, including transgender realities. It should also be noted that it had an impact because it came out of Paula Cooper Gallery … so Benglis’s voice was not the lone woman wanting to be heard … she was already with one of the top galleries. Something had gotten her there, and other things [much larger] were at work.

I consider myself a feminist because I believe in equal rights for women. I came of age during the civil-rights era, which, by extension, included women’s liberation. I have never had the slightest compunction to avoid that identity, and yet it isn’t a primary label for my work, because I want to make art, not propaganda. Even in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s, when my work was oriented toward gender politics, I was committed to, first, a visual experience and, second, a surprising, thought-provoking experience.

KRISTEN SCHIELE (b. 1970)

I find the Lynda Benglis ad playful, in your face, and completely free. It makes me laugh. It proposes a dialogue that is constructive and perhaps controversial for some, but better than the media frenzy over “sexism” that has been happening this month over small shows and reviews.

The Benglis ad is relevant and fresh. It presents an interesting legacy and is alive today with its challenge being both questioning and playful. Historically, it is brilliant sensationalism that helps involve us into greater challenge and leadership thanks to a dialogue she helped start. It proposes a dialogue that is constructive and perhaps controversial for some, but better than the media frenzy over “sexism” that has been happening this month over small shows and reviews. I am grateful for it.

VANESSA ALBURY (b. 1978)

Lynda Benglis’s ad was a powerful and clever move, bringing attention to the state of women in the 1970s art world. The subversive nature of sexism requires developing techniques to confront it. Tactics once powerful are often later enveloped into the morphology of the problem. Artists today can take a page from Benglis’s book, using humor and fearlessness to point out the unacceptable state of the status quo. Reflecting of Benglis’s ad, I think be brave, be clever, and keep going. Benglis is part of a rich art history that defies the norm to get a message out there, and I aspire to stand on her shoulders.

I am a feminist, and being so has helped my career by educating me on the gender dynamics marginalizing women — and anyone who isn’t a white, heterosexual male — that we face, informing my perspective on what matters in the art world. Observing the low exhibition and collection statistics of living female artists in relation to the numerous amazing works by well-known and emerging female artists, like Sue de Beer, Marlene McCarthy, Rachel Rampleman, Jamie Diamond, Juliet Jacobson, Marthe Ramm Fortun, and Afruz Amighi, has helped me to shape my art career and inspired me to see the sociological impact of choosing to be an artist daily and to engage in the future history of women in art.

DONNA HUANCA (b. 1980)

The Benglis image reminds me of the energy of punk rock, which in many ways introduced me to [the concept of] feminism. I was a drummer for many years and would tour in a miniskirt. I was very good but could never get past the sexist remarks — “You’re good for a chick drummer.” What makes me laugh is the farce that the art world is supposed to be a safe place for women, assuming intellectuals are somehow enlightened by academia and can finally see and treat women as equals. Experiences have proven that being a woman, and working with fierce, unapologetic women, will always bring out the primal sexist realities in others.

RACHEL FOULLON (b. 1978)

I first learned about Benglis’s ad in a critical theory class at NYU in the ‘90s. It fascinated me, because in addition to its shock value, it had no direct visual relationship to the abstract paintings and poured sculptures I knew her to make. Her ad allowed me to see that an artist’s politics don’t need to always serve the content or themes within their work, and vice versa. They don’t have to look the same. One can be radical as an artist in more than one way, fight more than one fight, and the overlap does not need to be explicit. This is a freedom that Benglis’s $3,000 has bought for me, and for that I’m deeply grateful.

Sadly, I don’t think what she did would even be possible anymore in this conservative, fearful, market-driven environment. Real change has to begin with money, since unfortunately that’s what speaks the loudest right now in the art world. Major collectors and the largest institutions would need to begin to place true and sustained investment in women artists at every stage of career. It would require an epic paradigm shift.

DARIA IRINCHEEVA (b.1987)

I saw the Benglis ad about 25 years after it was published, as I was born in 1987, so I always perceived it from the historic perspective. By the time I had seen it, it was already “packed” in its historic context with other influential female artists such as Eva Hesse, Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann, and many others. The whole story influenced and encouraged me a lot and in many ways. I was very honored to be Lynda Benglis’s student at SVA; she was one of the most critical and inspiring professors I had.

I consider myself a peaceful, “silent” fighter for freedom and equality. I believe that right now our global society is unbalanced, and I do my best in my own life to prove first of all to myself that we can all be equal. The global society I dream of for the future will have the same education and health care for everyone, in every country. The planet will function as one single organism working on the most interesting questions, exploring our nature, and the micro and macro cosmos we live in. I understand it will probably happen after I’m gone, but this dream keeps me going and helps me to stay positive and active. I understand that right now women have much fewer possibilities for growth than men, and I consider myself a feminist in the way that I don’t believe that one gender is better than the other. It should be an organic cooperative function, like how our brain works; both the left and the right hemispheres should be equally engaged in solving tasks and problems.

JENNI CRAIN (b.1991)

Because of contributions by artists such as Lynda Benglis, we have reached a moment when work does not have to overtly or explicitly address this still-paramount discourse. For this I am wholly grateful and implicitly proud. Yes, the conversation is inherent within my work as a young, female artist, and its residual footprints will undoubtedly affect my work and career as it transpires. Underrepresentation is still a reality. As always, awareness is the foremost inciter in eliciting revision, as is perseverance and an embracement of nonpartisan inclusion, in the arts and elsewhere. I am, absolutely, a feminist.

CHERYL POPE (b. 1980)

This ad was and still is a very powerful and iconic image representing the female artist. I think it represents the identity of the female artist today. Benglis embraces this super slick and sexual female/male identity that is confident, seductive, and suggestive. The duality of embracing and employing her femininity while complicating it with masculinity — short hair; sleek, slender torso; and double-sided dildo — for me it is the struggle to balance both, to present both and live as both, [that is necessary] in order to succeed in the art world.