My wife Heather and I are both avid listeners of “Serial,” the public radio podcast that reinvestigates a 1999 murder in Woodlawn, Maryland — just a few miles from Baltimore, where, as it happens, we live. A couple of weeks ago Heather had to take a medical licensing exam at an office park in Woodlawn itself, and as we drove out we realized we were passing through the show’s geography. Our car suddenly became very grave. “So this is it,” I said as we went through Leakin Park, where the victim’s body had been discovered, and I realized my voice sounded solemn, a little church-y. We had our eyes out — everything seemed like it could be tinged with significance — the basic sociocultural advertising of the place, the size of the high school, and the dimensions of its roads (which figure in the murder). How shady was it, how safe, how diverse? I mean, ridiculous, right? What a couple of big-eyed yuppie weirdos. But of course this put us not so far from the style of the show’s producer, narrator, and star, Sarah Koenig, who plays herself as a kind of amiable, obsessed doofus who troops through Woodlawn, a place she doesn’t really know, looking for truths about the place and its inhabitants that the natives might have missed, in the hopes that she might right a wrong.

Something has bothered me a little bit about this pose ever since last week’s episode. Since then, two high-profile critiques (one by Jay Caspian Kang, at the Awl, and another, somewhat less compelling, by Julie Carrie Wong at BuzzFeed) have made different versions of the same argument: that Koenig, a white reporter documenting a case whose key actors were all not-white and that requires her to understand the dynamics of minority and immigrant culture, succumbed to her own privilege. I disagree with the racial aspect: Maybe there is some minor cultural mischaracterization, but so minor that it feels inevitable, and Koenig really does go out of her way to try to understand honestly what being the kid of immigrants meant to the principals, in a way that the cops and prosecutors never really seemed to. Major points for trying, is my opinion. But it does seem to me that Kang and Wong are right to raise privilege as a problem. Not racial privilege, exactly, but the more basic privilege that a nonfiction storyteller enjoys, to aestheticize real life, to wonder why all the details don’t fit, to say what makes sense and what doesn’t — the privilege, most of all, to explain to the world what these people were like.

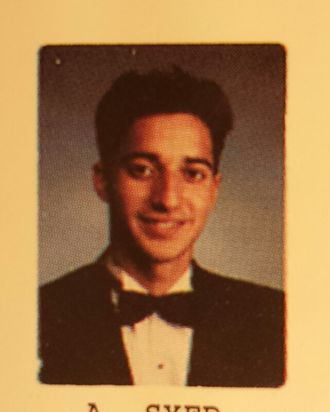

“Serial” documents the murder of an honor student at Woodlawn High School named Hae Min Lee, for which her ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was convicted. Adnan (Koenig always uses first names, so I will, too) has always maintained that he had nothing to do with Hae’s murder, and the case against him was built almost entirely on the testimony of a friend of his, named Jay, who said he helped Adnan bury Hae’s body, though his testimony changed several times. From the outset of the series, it has been obvious that the case rested on Jay — either he was telling the truth, in which case Adnan did it, or he was lying, either because he committed the murder or because someone he knew did.

In the eighth episode, an amped-up Koenig finally interviews Jay — in his mid-30s now, a decade and a half after the murder — for 20 minutes. The interview takes place with audio off, so we don’t hear the actual conversation, just an account of it. But it resolves exactly nothing. Jay maintains that the account he gave was truthful and, though polite, is a little angry that all this is being dredged up after all of these years. By the end of the episode the listener has heard a pretty deep inquiry into Jay’s character. Koenig reports that many of Jay and Adnan’s friends were surprised that Adnan, a stellar student, might be wrapped up in the murder, but few were surprised that Jay might be. We’ve heard about Jay’s weed-dealing, his employment at a porn video store, his broken home. “Serial” doesn’t give Jay’s last name, but you can find it easily by Googling, along with links to his Facebook page. He isn’t just part of “Serial“‘s narrative world, but of the real one. If Koenig does not have the goods on Jay — if she can’t establish by the end that he has lied in order to cover up his own deeper involvement, as the narrative often suggests he might have — then it is hard not to feel that he has been very badly used by the show. (There are others who are similarly, speculatively, connected to the crime — a defense lawyer at one point idly wonders why police did not investigate a man named Don, Hae’s boyfriend at the time of the murder.) You begin to wonder, Why does “Serial” get to speculate so publicly and so intimately about these people, anyway?

There’s a pretty telling exchange that comes at the end of “Serial“‘s sixth episode, when Adnan, calling for the millionth time from prison, asks why Koenig is so interested in his case anyway. It’s Adnan himself, Koenig says. She thinks he’s a good guy. It doesn’t make sense to her that he would kill someone. There’s an awful lot of this kind of talk throughout “Serial” — zeroed in on the matter of what people are really like, on characterization. (The eighth episode was titled “The Deal With Jay,” meaning in part, What’s the deal with Jay?) The show’s most emotionally intense moment comes when Koenig suggests that Adnan might have had a “deep, dark” side that his friends could not have seen. (Adnan, as you might expect, reacts angrily to this.) A great deal of time is spent on the nuances of Adnan’s character — on his relation to his parents and their tradition, on his perception within school. All of which is interesting, and some of it important, but at a certain point you get the sense that “Serial” is aiming for insights of the George W. Bush–on–Vladimir Putin brand — gazing into the souls of its characters, trying to discern who is capable of horrible acts and who is not.

The basic seductions of “Serial” lie in the genius of its cadences, of how slowly things unravel, and in Koenig herself, who is incredibly appealing. But it has a secondary urgency, too, more political: It arrives at the end of a remarkable and long American transformation on crime and punishment. (It would have been pretty amazing, on the date Adnan was convicted, to be told that the one point on which Republican and Democratic congressmen seemed poised to agree in 2014 was that criminal justice was dispensed unfairly and that sentences were too long.) What “Serial” does brilliantly is detail the conditionality of facts that can be used to put a person in prison for many years — the way many details, when you really examine them up close, can begin to seem a little more watery, less solid than you might expect.

But Koenig isn’t a criminal-justice professional. Her interests aren’t confined to the strict matter of whether the jury should have convicted. When she introduces the pros — a law professor at the University of Virginia, a former homicide detective whom she hires as a private investigator — they tend to sweep aside whole segments of Koenig’s interest, mostly those having to do with what the people in her story were like, to focus on harder facts that can be proved or disproved. “Subjective,” the detective called a long inquiry Koenig launched during this week’s episode, into how Adnan behaved just after the murder but before his arrest, and advised her to set it aside. But a few minutes later, Koenig is back at it, introducing a good friend of Adnan and Hae’s named Christa. “She’s not in the … camp of ‘100 percent there’s no way Adnan did this,’” Koenig says, introducing her. (And notice that that is Koenig’s paraphrase, not Christa’s own words.) “She’s more in the camp ‘If he did then there’s no way I understand human beings. Because the guy I knew … ’ Et cetera.”

Big questions for a podcast. Pretty “This American Life”-ish, too. (Serial is a TAL project.) It’s got that late-night-bullshitting-with-the-RA vibe that public radio tries for so often. Early on in “Serial,” when I got frustrated with Koenig, I thought of this as a basically journalistic quirk, one that I often suffer from, of loading onto actual events existential meaning that the journalist is much more interested in than anyone involved, in which everything is reduced to a matter of character. But this week, I noticed that Koenig wasn’t alone. The psychologizing was everywhere. Koenig quotes the trial judge, speaking to Adnan just before she sentenced him to life. “You used that intellect. You used that physical strength. You used that charismatic ability of yours that made you — what was it — the president, or the king, or the prince of the prom.” (Keep in mind that Adnan has stayed silent throughout his trial — any charisma the judge detected was that.) “You used that to manipulate people. And even today I think you manipulate even those who love you.” The presumption of intimacy here, the judge’s conviction that she can know the person before her, and that what she is judging is his character, is astonishing.

We’ve been slowly getting more sophisticated about crime, as a country. We accept, or most of us accept, that the conditions for criminality are set in part by social circumstance, that a kid born deep in East Baltimore is more likely to commit a violent act than a kid born in the suburbs. There is free will in crime, but it is a conditional form of free will. But we still tend to load up crime with a deep meaning that it can’t always hold, that doesn’t really acknowledge that conditionality. It is striking, in a story of a murder that we experience through the double secular filters of the law and public radio, that there is still so much theological language and thought kicking around, of innocence and guilt, of repentance and redemption.

I think this is where the privilege lies in “Serial,” and it is what makes the story told there seem at times uncomfortable or intrusive. It’s not exactly in the racial dynamics, and not only in the way that Koenig tells the story. It has to do instead with the psychological tourism that comes in the aftermath of a crime, the license that everyone (Koenig, her audience, but also the cops and prosecutors and judges and Hae and Adnan’s classmates) feels to gaze into the lives of both victims and the accused and to wonder about the extent of what people are capable. There’s insight to be won there. But there is also a very basic risk, that the journalist and the judge alike will wind up making drive-by assessments of other people’s real lives, that they won’t be too different than the gaping yuppies tooling through a suburb and throwing adjectives out the window: shady, creepy, guilty, good.