One of the spring’s most enjoyable new comedies was Sarah Ruhl’s Stage Kiss, a big wet smooch on the lips to theatrical narcissism. Raucous and ribald, it fit uncertainly in the trajectory of an author better known for the quietly measured teaspoons of drama in works like The Clean House and Dead Man’s Cell Phone and In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play). Turns out, Stage Kiss was a bit of a blip stylistically. Her new play, The Oldest Boy, at Lincoln Center Theater, finds Ruhl returning to (and thoughtfully extending) her familiar dramaturgy, which involves likable women muddling their way through oddball situations like metaphysical Lucys. Those outré plots are decoys, though: brightly colored attention-getters built to allow her real interests, which are somewhat vaporous and philosophical, to slip by undetected. Which is fine, lovely even, when the plots float. But sometimes a vibrator is only a vibrator. Or, in the case of The Oldest Boy, a lama only a lama.

A little lama at that. Tenzin, nearly 3 as the play begins, is the son of a white lapsed-Catholic mother and a Tibetan Buddhist father in exile. The Mother (she is given no other name) seems at first to be a caricature of conflicted on-trend moms, practicing meditation with her iPhone and baby monitor next to her on the floor. The baby monitor signals one of the themes of the play: attachment, or over-attachment; who still uses a baby monitor during a talkative toddler’s naps? In any case, her attachment is to be sorely tested with the arrival of two Buddhist monks, who are not expecting to find this kind but entitled American lady any more than she is expecting visitors who will make a claim on her child. For the older monk, a lama, believes that Tenzin may be the reincarnation of his beloved teacher, who died almost three years earlier.

The child himself appears to confirm the idea, saying uncanny things that suggest knowledge of his previous life, and succeeding at all tests put before him. These are beautifully conceived by Ruhl and staged by the director Rebecca Taichman to create suspense; after all, children are very suggestible and also fantastic fiction-makers. Could he be gaming them? Still, this too is a decoy; Ruhl isn’t much interested in suspense of the type created by the “Is he or isn’t he?” question, only in what the mother (and to a lesser extent the father, an underrealized character) will do assuming he is.

The swift theatricality of the presentation makes up to some extent for the lack of drama. (The parents fight only a little.) No time is wasted on scene changes, whose place is taken by Tibetan-style movement and rituals. (The subtitle is “A play in three ceremonies.”) Instead of “normal” scenes, most of the action proceeds by various forms of story theater: jointly narrated reminiscence, direct address, dance, prayer, pageantry. Tenzin is portrayed by a gorgeous puppet, the work of Matt Acheson. I didn’t mind this lack of naturalism; in a season fairly bristling with it, I rather found it soothing, even if it also risked crossing a line into laxness. What I missed was psychology, another traditional component of drama that Ruhl doesn’t seem to be interested in. When the Mother talks of being drawn to Buddhism because it was “something spiritual … that was also rational” and because it made her happy — “well happier” — this is a conflict of philosophy, not emotion. And lest we be uncertain, Ruhl underlines the distinction in a subplot about the Mother’s failed career among deconstructionist academics: “English departments are the worst place in the world for someone who loves books.”

This dry line gets a big laugh (as many do) because Taichman, usefully pushing back against Ruhl’s predilections, ladles a fair amount of humor and, yes, even psychology on top of the story. The Mother doesn’t just eat potato chips as indicated in the script but gobbles them ferociously and then stashes them behind a pillow when the guests arrive. Later, she tears up a crucial photograph that Ruhl leaves intact. Taichman is abetted in her re-humanizing agenda by Celia Keenan-Bolger as the Mother. As was evident most recently in The Glass Menagerie, Keenan-Bolger is an extraordinarily “live” and legible actor, irrepressibly emotive; here she offers a kind of questing petulance that suits but also justifies the somewhat-loaded schema of the childish American mother who wants to think bigger but can’t. I don’t mean to say that these approaches to character are made despite Ruhl; clearly, they are possible because she has written the possibility. But it would be quite easy to play The Oldest Boy as the script seems to suggest, and that would be disastrous.

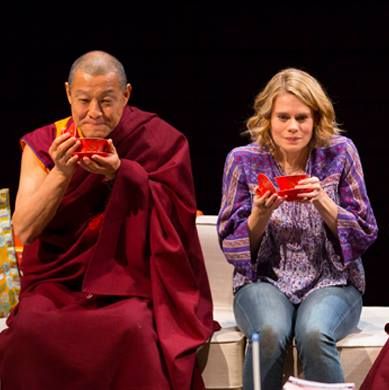

As it is, in a beautiful production that also features fine work from James Yaegashi as the Father, James Saito as the kindly lama, and Jon Norman Schneider as the beamish monk, there is something a bit embryonic about The Oldest Boy. Perhaps because the Mother is written as a kind of dilettante, having given up her own intellectual passions in favor of her child, I couldn’t help feeling a whiff of the dilettantism in the entire conception. Ruhl says she began it after many talks with her children’s Tibetan nanny, to whom the play is dedicated, in part. Not that there’s anything wrong with open-minded innocence in the exploration of other people and ideas, but combined with the suppressed psychology and mild dramaturgy here, it doesn’t leave very much of a play in the conventional (which is to say Western) sense. Though the lama states clearly that attachment is not the same as love because “attachment is not comfortable,” the question is not decided, or even truly dramatized. For all its sweetness, and the freedom it offers audiences to take it wherever they like, The Oldest Boy is nicer than it is gripping. I wish it were less loving in that sense, so it could be more attached.

The Oldest Boy is at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater through December 28.