This week, Vulture will be publishing our critics’ year-end lists.

1. Lila, by Marilynne Robinson

“Who in the world could need help with a chair?” This is what the protagonist of Marilynne Robinson’s new novel wonders when her husband pulls out her seat at the table. So much of Lila is present in that sentence: her pride, her self-reliance, her mistrust of kindness, and the way that — in her feral, gifted, autodidact’s mind — a profound alienation from society turns anthropologically keen.

Readers of Robinson’s 2004 Gilead have met this character before, through the eyes of that husband, the Reverend John Ames. Now, in Lila, we hear her story directly. Born into poverty and neglect, abandoned by her meager community in the worst of the Dust Bowl years, Lila would be as low and aimless as dust itself — but for her mind, and her huge and startling will. She yearns for love, and she yearns to understand “why things happen the way they do.” Ames helps on both fronts, and she helps him. Still, the nature of life troubles her, and her love for her husband does daily battle with incomprehension and shame.

Lila is gorgeously written, uncluttered yet made of everything, intellectually and theologically formidable. It could win a staring contest with the late Christopher Hitchens. And it wins, by an awesome margin, my vote for the greatest novel of the year. Midway through it, Lila recalls a story she once heard about a cyclone crossing a river. “It took the water in its path up into itself and crossed on dry ground,” Robinson writes, “and it was just as white as a cloud, white as snow. Something like that would only last for a minute, but it showed you what kind of thing can happen.” Exactly.

2. Family Life, by Akhil Sharma

In this restrained, meticulous, beautifully written book, a family emigrates from India to America, where an accident in a swimming pool renders the elder son brain damaged. Told from the perspective of his younger brother, Family Life is about how we assimilate, not just to a new culture but to any drastic change: imperfectly, at great cost, with glimmers of unsettling gain.

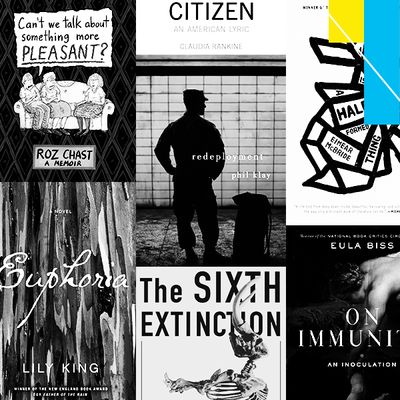

3. Redeployment, by Phil Klay

In 12 remarkable short stories, Klay, a former Marine and Iraq War veteran, captures the diversity of wartime experience, the depth of its psychic toll, and the difficulty of bridging the gap between front line and home. The result is profane, funny, horrifying, and, ultimately, humane.

4. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, by Elizabeth Kolbert

A crystalline, rigorous, fascinating account of the five mass die-offs in the history of our planet and the sixth one we ourselves are now causing. As chilling as you would imagine but terrifically important, and — thank you, asteroids, dinosaurs, and excellent writing — loads of fun to read.

5. Euphoria, by Lily King

This year’s winner, Book I Read in One Sitting Because I Happened to Read the First Page. Based on the life of Margaret Mead and set in the 1930s, anthropology’s problematic heyday, Euphoria is a novel of ideas that is also a novel of emotions: the titular one but also envy, hubris, despair, and above all desire — how liberating or scandalous it can be, how linked to the intellect, how dictatorial.

6. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, by Roz Chast

From our poet laureate of anxiety and neurosis, a deeply moving book about how we face, or avoid, both love and death. Never has Chast’s rumpled, palsied cartooning style seemed more apt, or worked so well, as in this funny, unsentimental, terribly sad memoir about watching her parents grow old and die.

7. Sidewalks, by Valeria Luiselli

Joseph Brodsky, Mexican geography, nostalgia, displacement, the moving maps in airplanes: Is there anything that doesn’t interest this young writer and that she cannot render interesting? Reminiscent of Sebald and Walser, unafraid of her own authority, Luiselli has produced an essay collection less heralded than many others this year and far better.

8. Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine

Part prose poem, part essay collection, Citizen anatomizes the operations of quotidian racism in the U.S. and the draining, Escher-like impossibility of navigating it. Cerebral, conversational, witty, upsetting, and generally brilliant, Citizen might be the book contemporary America most needs to read.

9. On Immunity: An Inoculation, by Eula Biss

Compassionate, lucid, and morally compelling, On Immunity simultaneously makes sense of the anti-vaccination movement, puts paid to its concerns, and puts it in context. “We are locking our doors and pulling our children out of public school and buying guns and sanitizing our hands to allay a wide range of fears,” Biss writes, “most of which are essentially fears of other people.”

10. A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, by Eimear McBride

The unnamed narrator of this story suffers abuse, neglect, incest, sexual violence, and her brother’s illness and tragic death — yet McBride manages to tell the story without manipulation or mawkishness by inventing for her protagonist a private grammar and sustaining it for 227 pages. What emerges is a self like safety glass after the wreck.

*This article appears in the December 15, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.