10 Black Artists on the Lessons of Ebony and Jet

Last month, the Studio Museum in Harlem opened an exhibition devoted to the magazines Ebony and Jet, their place in black culture, and the artists who’ve been inspired by them. Speaking of People, Ebony, Jet and Contemporary Art will be on view until March 8th (a slide show excerpting the show is below), and while it was up we thought we’d reach out to black artists working today — not just those in the show, but others as well — to asked about their relationship to Ebony and Jet, the significance each title had for them as they were growing up, and what these magazines in particular can tell us about the place of black culture in America now (in particular as it relates to art and artists).

Derrick Adams: Jet and Ebony as a media force have always reflected and highlighted the things I saw around me growing up every day, as well as witnessing family members transform themselves into what they saw on the pages in these publications. I can imagine people thought that finally there are black magazines promoting various choices as a sign of progress and forward thinking in the black community.

Jet and Ebony are now an encyclopedia or archive of African Diaspora culture from the publications’ origins to date. Everything from dramatic fashion spreads, to flipping the pages to images of black and white American celebrities protesting against Apartheid in South African, to a profile of a black astronaut has been featured. They really tried to cover a lot within the restraints of a commercial-magazine format. It’s an aspirational database.

Both publications paved the way to many other successful print magazines; lifestyle websites and blogs continuing what these pioneers had formed. Now many diverse American groups have particular interests and are making their own rules and presentations. Jet and Ebony played a major part in showing that communities should highlight and appreciate what is unique about their culture, including local artists and fellow artisans.

Mark Thomas Gibson: I guess I was lucky to some degree growing up because I just thought black bodies and images lived everywhere. When you see Jet magazine and Ebony on every coffee table, in every doctor’s office, and on a lot of car seats, you can easily take it for granted. To see a thriving black middle class mixed in with celebrities and entrepreneurs didn’t seem so foreign at the time; it wasn’t where I lived but it wasn’t foreign. Jet, in particular, stood out. It read like a newspaper bulletin laying out recent black news. As an artist, my first figure models came in the form of Jet beauty. Looking back, the images were still and repetitive, but it worked for me. It wasn’t like Miss America where there was a false pretense of being able to answer questions about world peace while spinning plates.

I never saw either Jet or Ebony as art magazines. For me, they are black lifestyle magazines. They covered all the bases of black life from music to fashion to politics and culture at large. It didn’t paint the black experience as “lifestyles of the rich and famous.” There always seemed to be a focus on saying, “This is accessible.” As an artist today, I realize that those early experiences with a positive and real image of black life are actually few and far between. When I look at media today, the images of black lives are narrow and isolated into celebrity or weekly TV drama. Now that I am in my mid 30s, I wonder what real image is out there for me in my current demographic that isn’t marketing to my youth culture.

Lyle Ashton Harris: My childhood experiences with Ebony and Jet publications were limited to when I would visit my grandparents’ home, as my mother did not subscribe to the magazine due to her engagement in a broader conversation. During that time, Ebony served as a conduit to find a sense of belonging and as a thread to black history and popular culture. However, it simultaneously struck a chord of ambivalence due to Ebony’s conventions around sexual difference, gender, and class.

That said, one of my greater influences was the Pulitzer Prize–winning Ebony staff photographer Moneta Sleet Jr. Sleet’s archive, whose legendary documentation of historical figures such as Billie Holiday and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. is still something that resonates with me today, specifically his work’s historical engagement with not just a local narrative, but its international presence.

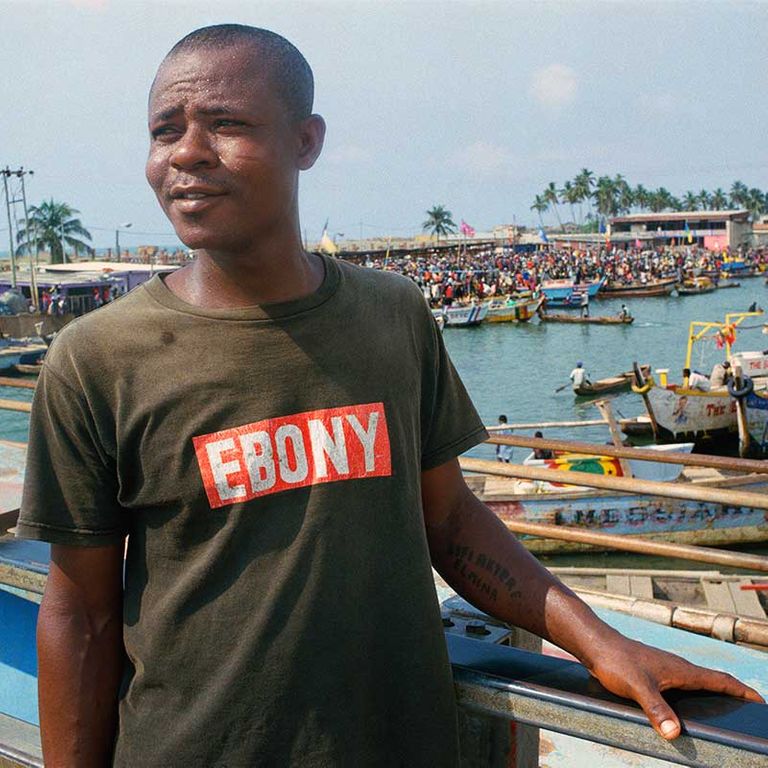

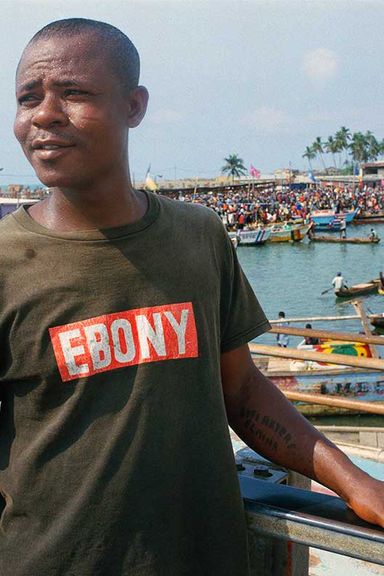

Over the years, my work has traced the shifts of Ebony’s cultural currency as well as my discursive and ambivalent relationship to the concept of Ebony. For example, my 1996 photomontage series “The Watering Hole” employs Ebony’s November 1990 45th anniversary cover as a way of pointing to the lack of visibility in regard to sexual difference and violence. And in my recent work, specifically Untitled (Elmina #1) and White Ebony, those shifts are positioned to cause a rupture in which these ideas, conventions, and understandings of Ebony as a global currency are challenged and produce a counter narrative.

Heather Hart: I remember spending hours in the mid-’80s staring at that Ebony cover of Sade (deciding I wanted to be her when I grew up). These magazines mirrored our beauty, evolved our critical and political eye, and echoed our optimism when every other mainstream news and pop context washed us with horrible stereotypes and perpetuated white privilege. From my little house in very white north Seattle, I was able to access the diversity of “blackness,” witness our evolution, and see successful families that looked more like mine. It was also in this issue that they presented a significant article featuring a group of contemporary visual artists. This is where I first saw Hughie Lee Smith’s work … which I fell in love with and influenced a deluge of my artistic choices in college — probably still does. Looking it up now, that same article also featured Martin Puryear, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Mel Edwards, and Sam Gilliam, who still influence me today and first showed me that conceptual and abstract work IS black art.

To me, Ebony now represents that coniuctio of nostalgia and foresight. The digital and social platforms that dominate today give us access to more and at a quicker pace, which Ebony is a part of. But I can still depend on their legacy of giving black culture and art a sense of history, value, and, most important, a context.

The challenge remains to find a context for work by black artists that isn’t inhibited by being viewed through a different lens than white artists. When a collector buys a piece of work by a black artist, they are forced to consider the political statement they are making by owning it. The privilege of being a white artist means that lens rarely exists. Having one’s work critically written about and presented in Ebony ideally still gives us a platform without that lens.

Adam Pendleton: When I was growing up, the staple magazines in my grandmother’s home were Jet and Ebony. My parents didn’t subscribe, but I always remember how striking the covers were to me; what other magazines featured African-American cultural icons on their covers, every issue? I didn’t realize it then, but it became a kind of visual history of the powerful trajectory of African-American culture in America. One can’t help but think about these publications in relationship to other legendary black magazines like Drum, which first appeared in South African in 1951 and was/is renowned for its reportage of township life under Apartheid in the ’50s and ’60s. These publications gave, and continue to give, an image and a voice to a collective consciousness, and have profoundly shifted notions of racial progress, beauty, and politics.

Hank Willis Thomas: I have always used Jet and Ebony magazines as an archive. They are like time capsules and time machines that bring you back to the mind-set, struggles, and values of African-American communities throughout the latter part of the 20th century. There is no more complete visual and textual archive of the 20th century black experience in America. I’ve known that for my entire life.

Now that print media is apparently in decline, I am concerned that it will be harder to have ready access to the benign and mundane aspects of black culture in America. You can pretty much open any page of an old Jet or Ebony mag and be amazed, intrigued, and enthused with the articles and headlines you find. There are so many nuances lost when we only focus on the “major” events. I find that you have to be considerably more precise to find interesting random historical facts and info through online research.

To date, I am not sure if there is another publication that has given me more shine. I think these magazines still function very much the way they always did: as a trusted resource for those interested in learning about the African-American experience. The major difference is that mainstream publications now see the value in highlighting people of African decent and speaking to that audience. There are more publications casting a wider net, including rather than excluding. There are also more organizations like theroot.com and thegrio.com that complement Uptown, Essence, and other black-oriented media. At one time, Ebony and Jet were the only major outlet. Now there are many avenues.

Damien Davis: I remember as a young child, my brother and I (often at the doctor’s office or the barber shop) would play a narrative game with the magazines in the waiting area. The game went like this: Each time we turned the page, one of us would have to come up with a story about what we saw, with the narrative continuing as we turned each page. The relevance each page had to the previous one didn’t matter, we just had to make the story flow from one page to the next. These connections would sometimes be difficult to talk out for a 5- and 6-year-old, but the both of us became very good at using our imaginations to bridge the many non-sequiturs we encountered thumbing through these magazines.

Jet and Ebony were always the best ones to play this game with. The stories within the pages were both familiar, but also aspirational, allowing us to import ourselves into some fantastic adventures across the globe. I think it was within the pages of these magazines that I first learned how to think creatively, and also affirm that I had a right (with hard work) to dream big for myself.

As I grew older (and the words began to make more sense), this idea of a “commonality between people of diverse backgrounds” began to resonate more and more with me. It fascinates me how these publications simultaneously feel familiar and foreign; inclusive on a demographic level, but alien at an individual level, owing to just how diverse the lived experiences of black people truly are. The potential tensions that arise from creating a more focused narrative of black culture is what drives the bulk of my artistic practice, as well as my interest in Jet and Ebony today.

Danny Simmons: Ebony and Jet magazines were always present in my house growing up. The first thing I went to in Jet was the centerfold, as most of my young friends did. But of course, the magazines were much more important purveyors of black culture than the monthly array of beautiful black women that adorned the pages and the ads. Mostly from my preteen years, I remember the coverage of the civil-rights era. The magazines were our main source of information into what was happening in Little Rock, Selma, and in Georgia. They told the story of Dr. King and the dogs, hoses, jails, lunch counters, and buses. They talked about lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, Bull O’Connor, George Wallace, the southern police, and the action and inaction that came from Washington, the Presidents Kennedy and Johnson and what it all meant to a little black boy in black Jamaica, Queens. Once Jet printed a picture of my dad with a bullhorn in his hand on the picket line while Ebony had ads of slick clothes and cool products, stories about singers and dancers, ball players and sports figures. I remember a monthly page by sociologist and historian Lerone Bennett that spoke about our past and great achievements. Of course both magazines detailed our progress, those who made it and the homes they owned and the big jobs they had; the Negroes who created businesses and the doctors and lawyers who served their community. There was always the listing of the top ten records and who were the new hit-makers. Jet in particular let me know who married whom, not that I ever knew any of them, but I was interested anyway because the magazines connected me to them.

Yet, I can’t remember any mention of the visuals arts. There might have been something about Gordon Parks because Gordon, more than an artist, was one of our outspoken celebrities right up there with Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Sammy Davis. The arts section was mostly restricted to the more entertaining aspects of the black artistic experience. As I got older, the magazine formats didn’t change, but the times did. Civil rights faded into revolution from conked hair to big Afros. The celebrities changed also, but I don’t remember much of a role for the visual arts on their pages. Integration slowly took place and the magazines on the coffee table that were reached for became Time and Newsweek, and although we still got Jet and Ebony, mostly out of loyalty, they weren’t our main source of news about black people. And as I think of it, the stories about blacks seemed to shift and those affirmations we got from our news press became stories of comparative successes via white America. Who made it in what corporation [versus] how bad things were in the ghetto.

Today I find myself looking once again towards those magazines for positive news. Now that black art is hot, every once in a while I’ll see a small story about an artist or a children’s art program or institution. [Today] we will still find that beautifully stunning, black pinup girl and stories about black businesses and black successes. Then, as now, those two magazines connect me to my community in ways that mainstream American magazines never have and never will. I hope they continue to inform us about us.

Iké Ude: As a very young chap, growing up in Nigeria, the twin publications Jet and Ebony offered me a fascinating portrait of Africans in the diaspora from their most exalted to the tragic — above all, I was more keen in analyzing their sartorial fluency and quotient. In this regard, Billy Dee Williams on the cover of Ebony magazine, January 1981, was so sartorially winning on all points that ever since it’s indelibly etched on my mind.

However, like most mainstream publications across the board, they are meaningless to me now. Regarding how the magazines tell us about the place of black culture within America now in relation to art and artists, they are not particularly positioned to do so and it is not necessarily their job.

Xaviera Simmons: Jet and Ebony, two very distinct magazines, were a major part of my growing up and developing a broader visual vocabulary and language surrounding black culture. I mean everyone in my family, my family’s social circle and most all of the black merchants, doctors, hair salons and barbershops had these magazines within immediate grasp. They were in pretty much everyone’s home or office environment as far as I can remember. Growing up in the 80’s and 90’s I always encountered these magazines whether I was in Harlem or in Maine. Where there were black folks living, there were Ebony and Jet. They were and continue to be an integral part of the visual fabric of being a black American. I am pretty certain that it was on the covers of one of these magazines that my eyes had many first sightings (seeing people of color on the covers) as they relate to their opinions on the visual and political climate of my youth.

As for what they mean to me now, Ebony and Jet is a part of a culture of reporting on the black experience that is cross-generational. I think across the landscape of black America you still find these magazines in most circles, in libraries, homes, and again in shops and medical offices.

These magazines report on political, pop, and art culture across the breadth of the African diaspora. They hold a special place in my heart because they are a part of the heartbeat of black America and African diasporic culture in general. Most important, I believe these magazines help bridge some of the generational gaps that can happen within any group. They are one of the few places where you can see a cross generational conversation concerning politics and art. A celebration of the works of someone like Elizabeth Catlett can be positioned alongside the celebration of younger generation artist like Glenn Ligon.

It’s very rare to see such a mix of art and culture with political content and conversations specific to the desires of African-Americans. It’s inspiring that these magazines have and continue to engage these topics.

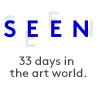

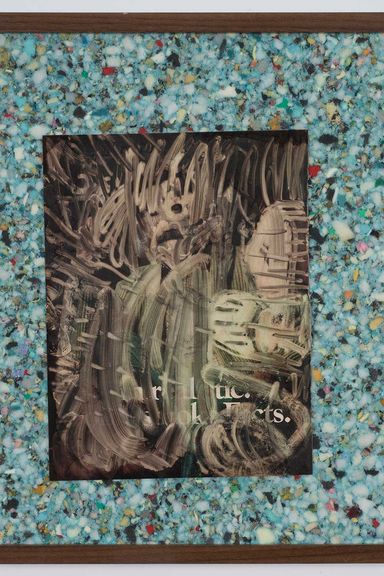

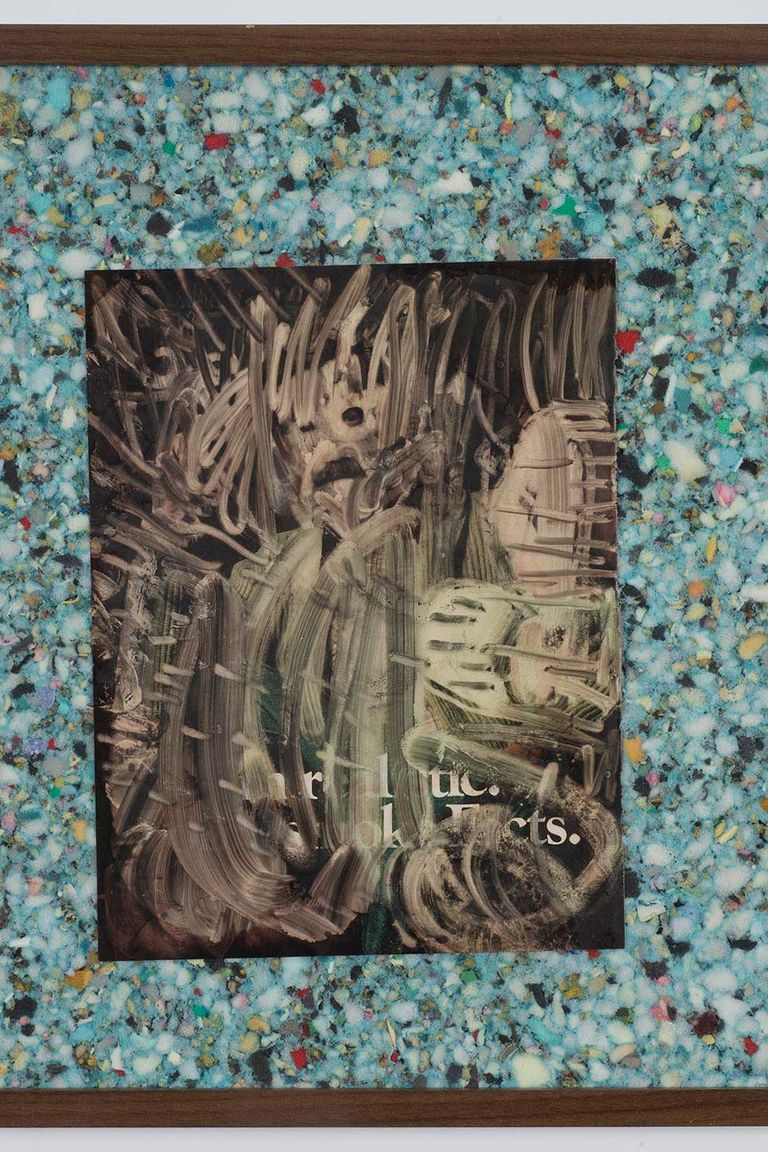

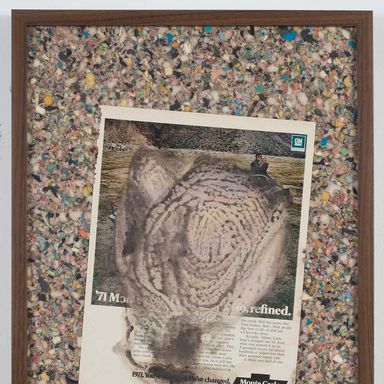

Noel Anderson, Ebony Painting 1, 2012; Manipulated Ebony page and carpet foam; 20-5/8 x 16-3/4 x 1-7/8 in.

Noel Anderson, Ebony Painting 2, 2012; Manipulated Ebony page and carpet foam; 20-5/8 x 16-3/4 x 1-7/8 in.

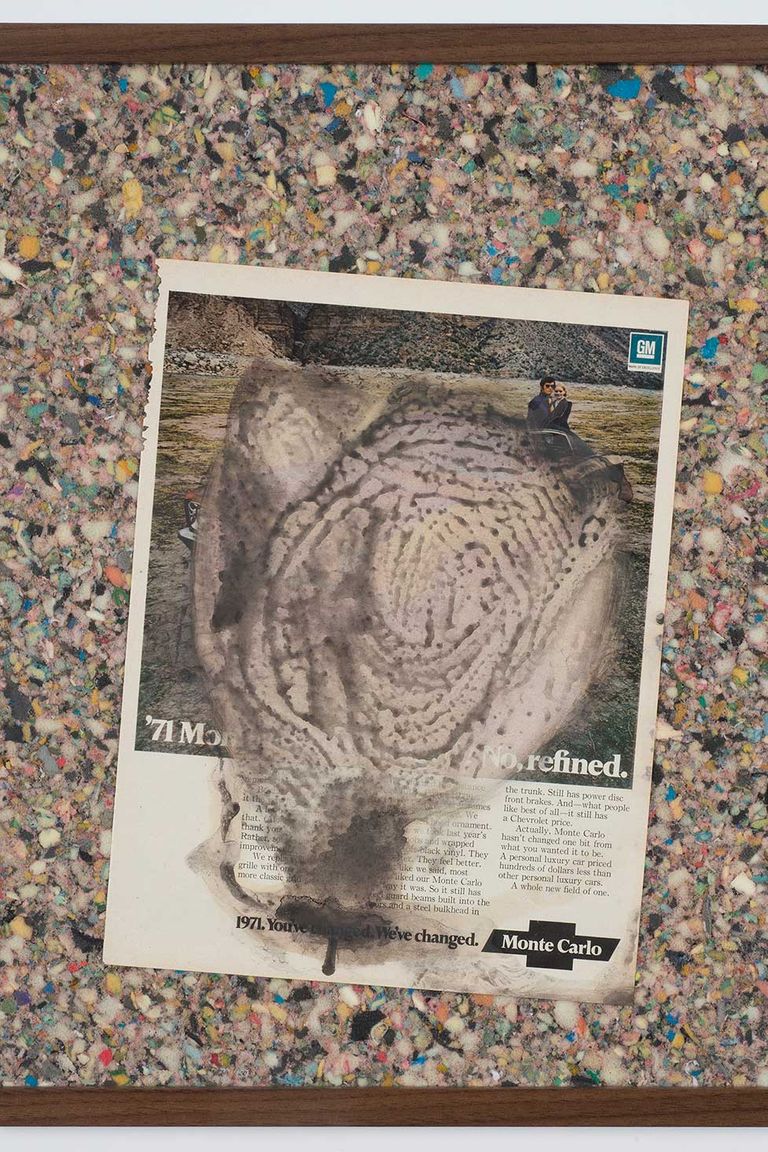

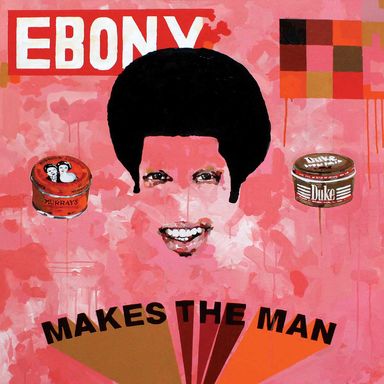

Jeremy Okai Davis, Makes the Man, 2012; Acrylic on canvas; 40 x 40 in.

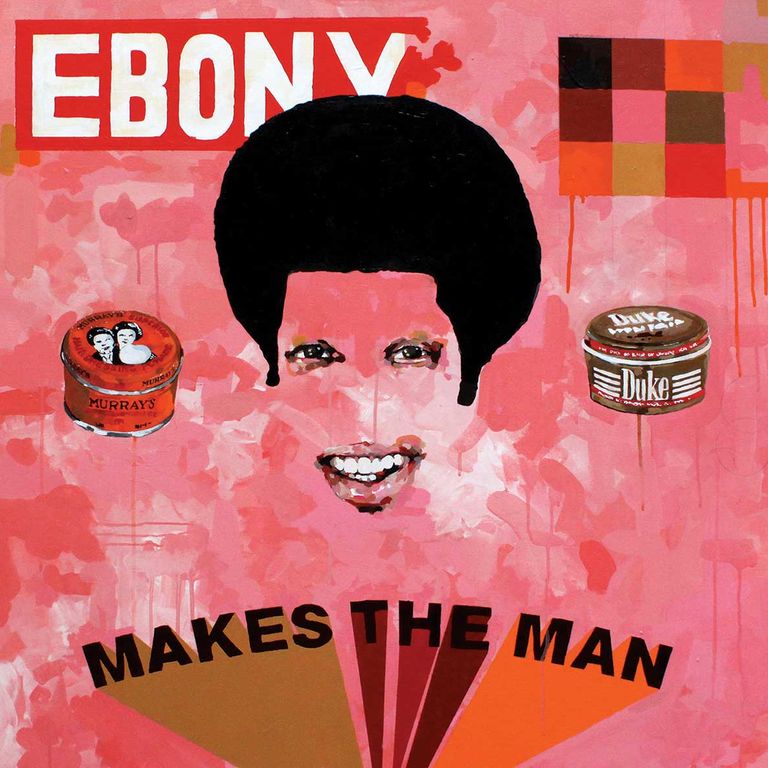

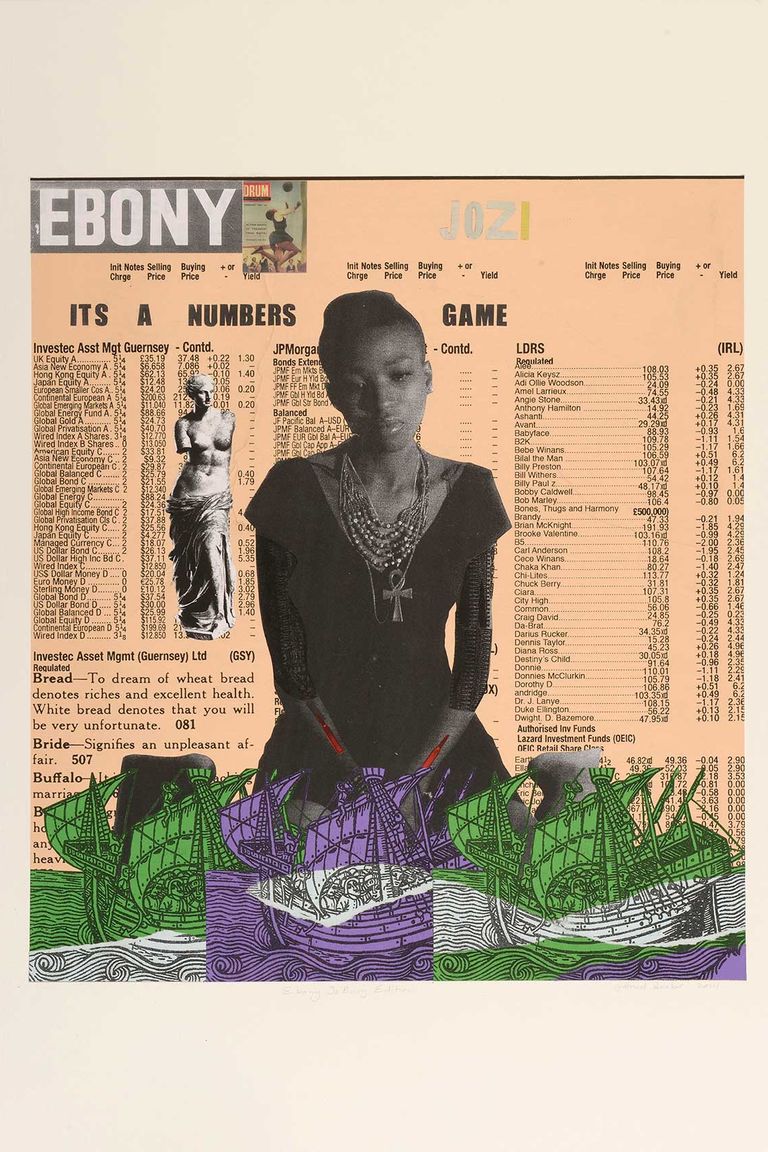

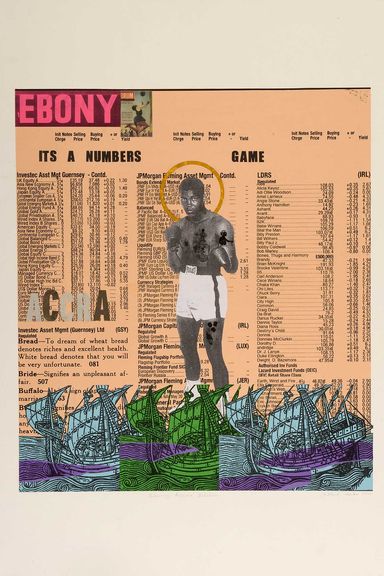

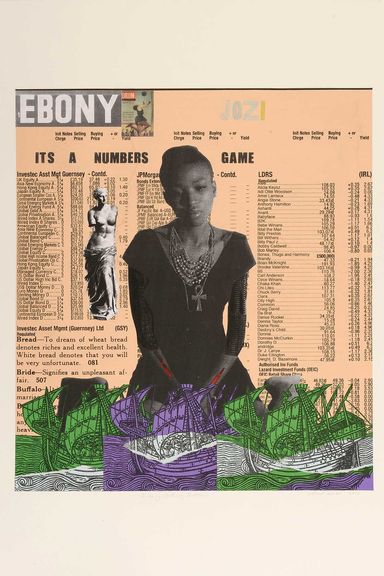

Godfried Donkor, Ebony Accra edition, 2014; Collage on paper; 27-1/2 x 39-9/25 in.

Photo: John Phillips

Godfried Donkor, Ebony Jo'burg edition, 2014; Collage on paper; 27-1/2 x 39-9/25 in.

Photo: John Phillips

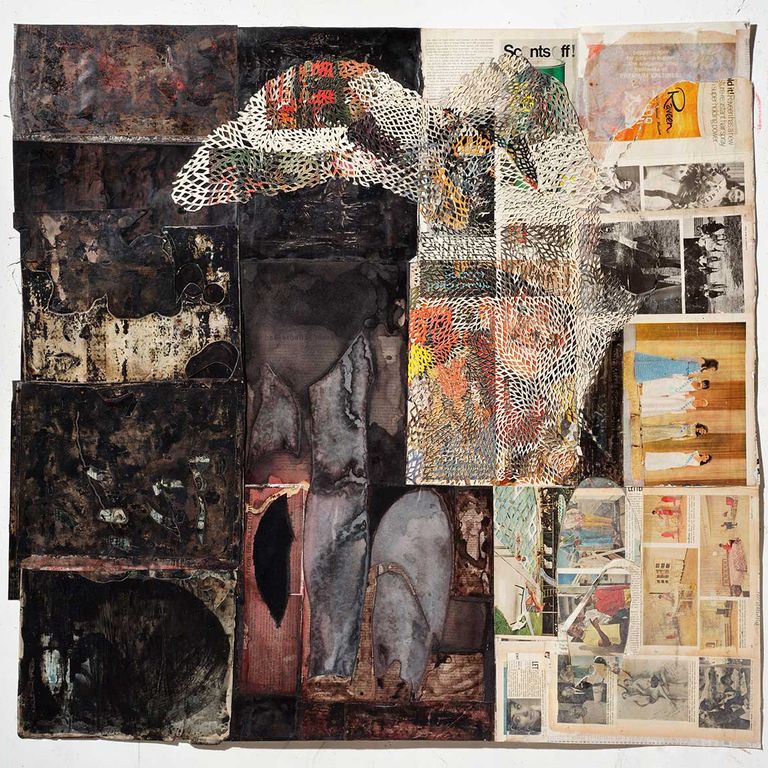

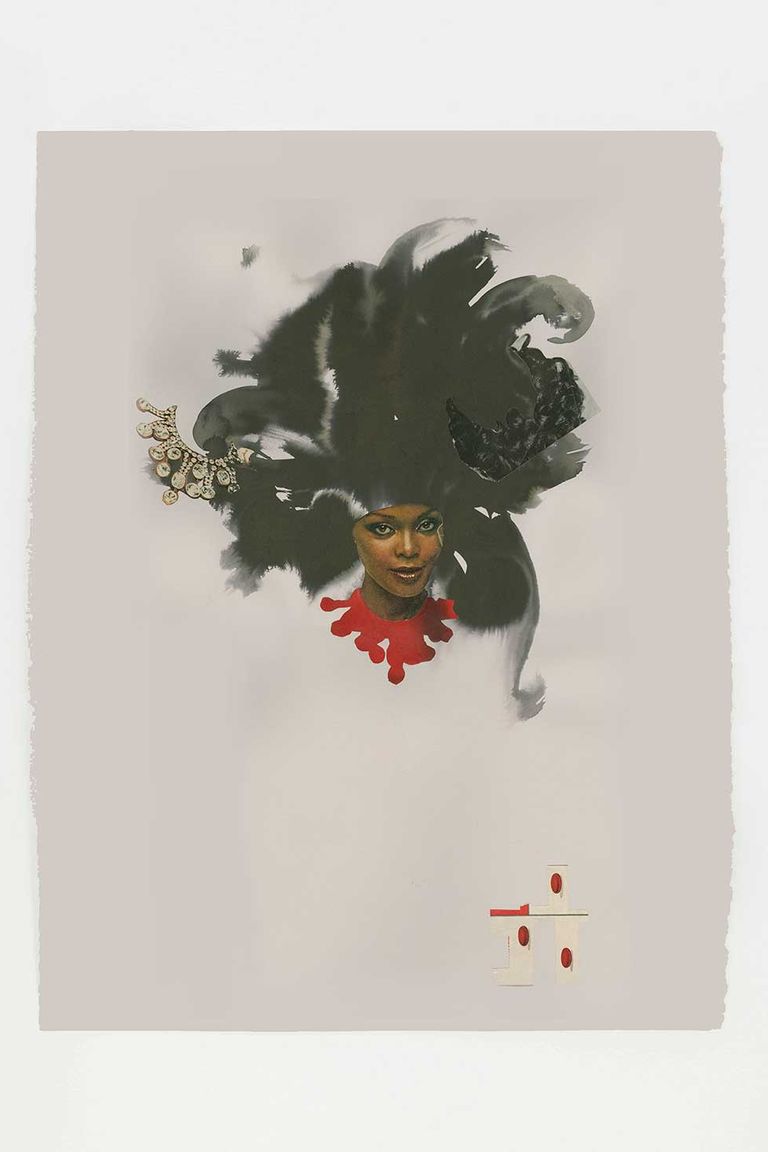

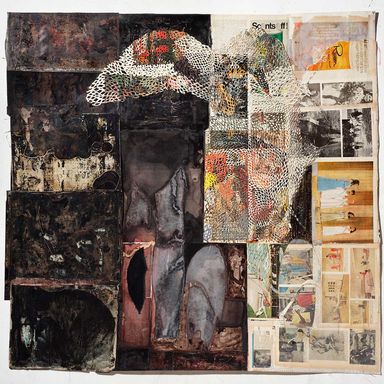

Ellen Gallagher, Hare, 2013; Ink, watercolor, oil, pencil and cut paper on paper; 44-4/5 x 46-3/5 in.

Photo: EllenGallagher 2013

Theaster Gates, My Beauty is Political (video still), 2014; Sound and color video; 2 hours 56 min.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Untitled (Elmina #1), 2008; Pigment on paper; 18 x 27 in.

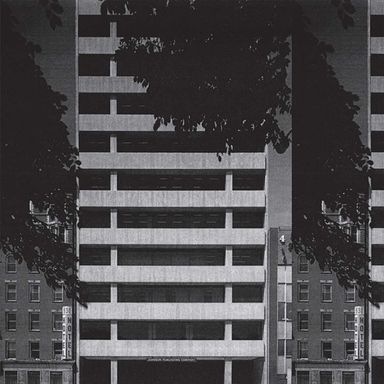

Photo: Lyle Ashton HarrisDavid Hartt, Carpet at The Johnson Publishing Company Headquarters, Chicago, Illinois, II, 2011; Archival pigment print mounted and framed; 60 x 80 in...

David Hartt, Carpet at The Johnson Publishing Company Headquarters, Chicago, Illinois, II, 2011; Archival pigment print mounted and framed; 60 x 80 in.

Leslie Hewitt, Flowers, 2013; Lithograph on paper; 10-1/2 x 10-1/2 in.

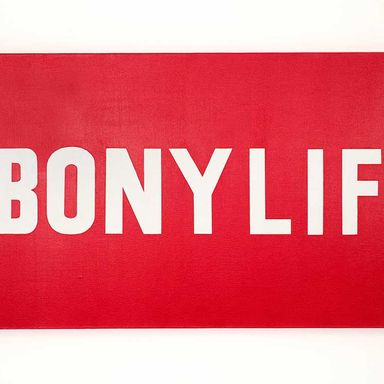

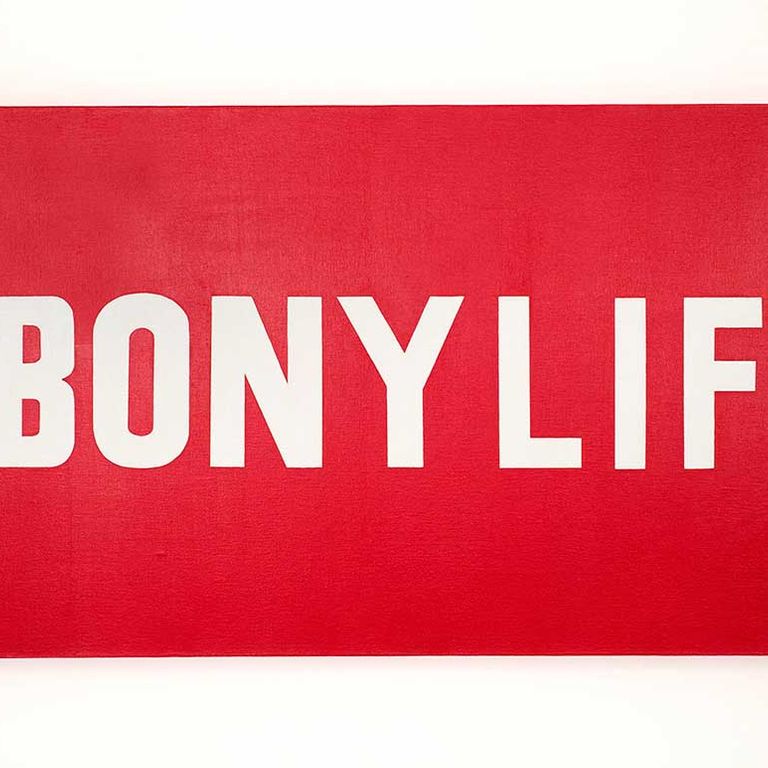

Hank Willis Thomas, Ebony Life, 2010; Gouache acrylic on canvas; 20 × 40 in.

Hank Willis Thomas, Jet People, 2010; Gouache acrylic on canvas; 20 × 40 in.

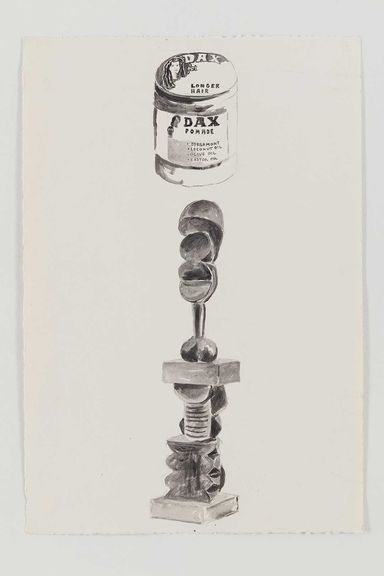

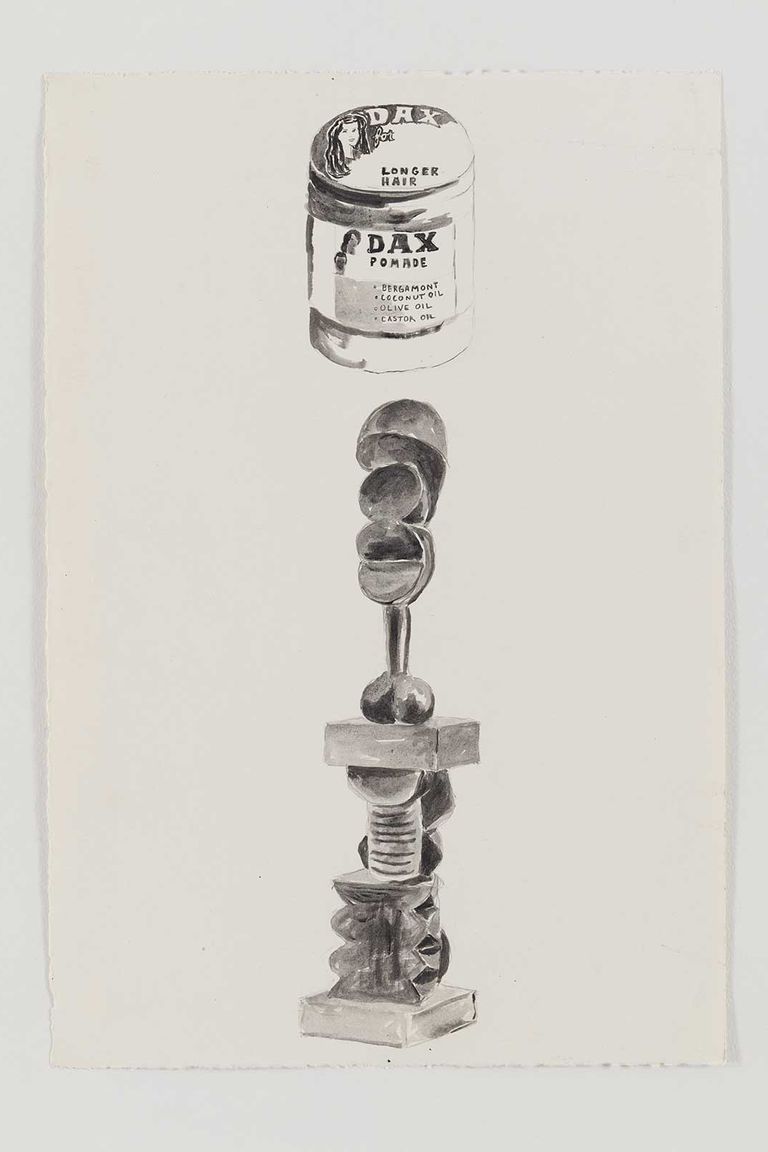

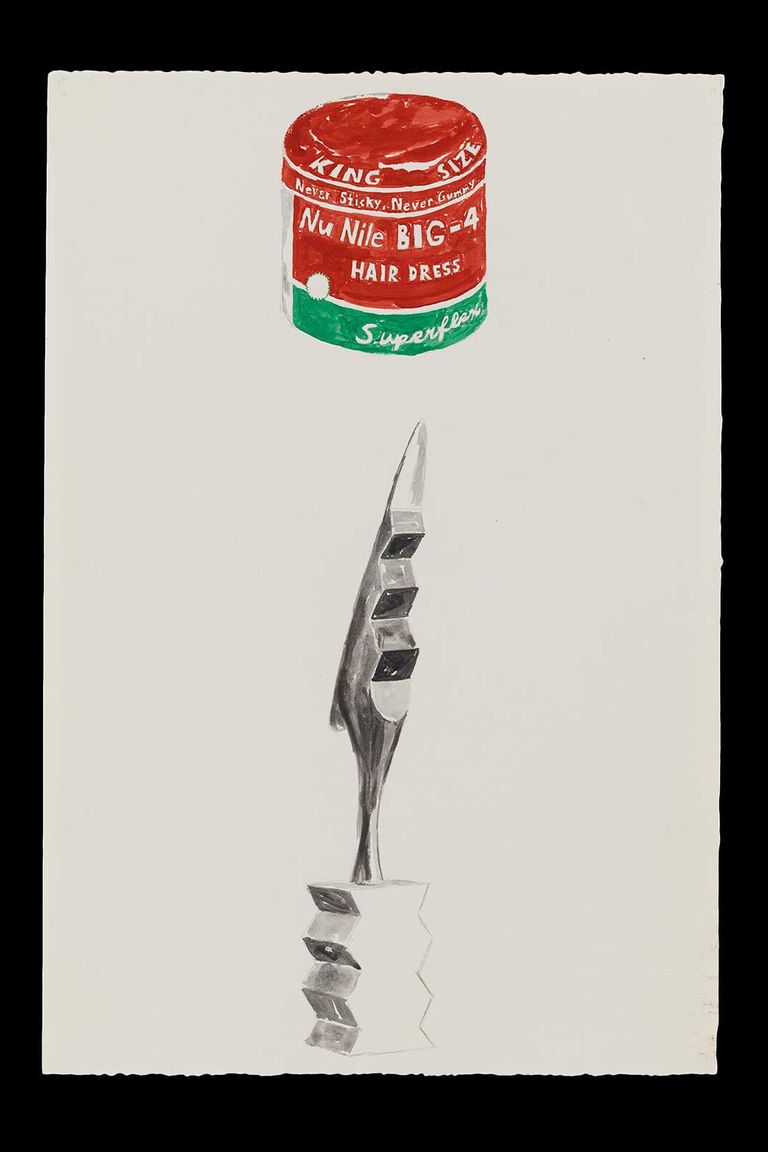

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (Dax Pomade), 1985; Synthetic polymer, ink, and graphite on paper; 22-1/8 x 15-1/4 in.

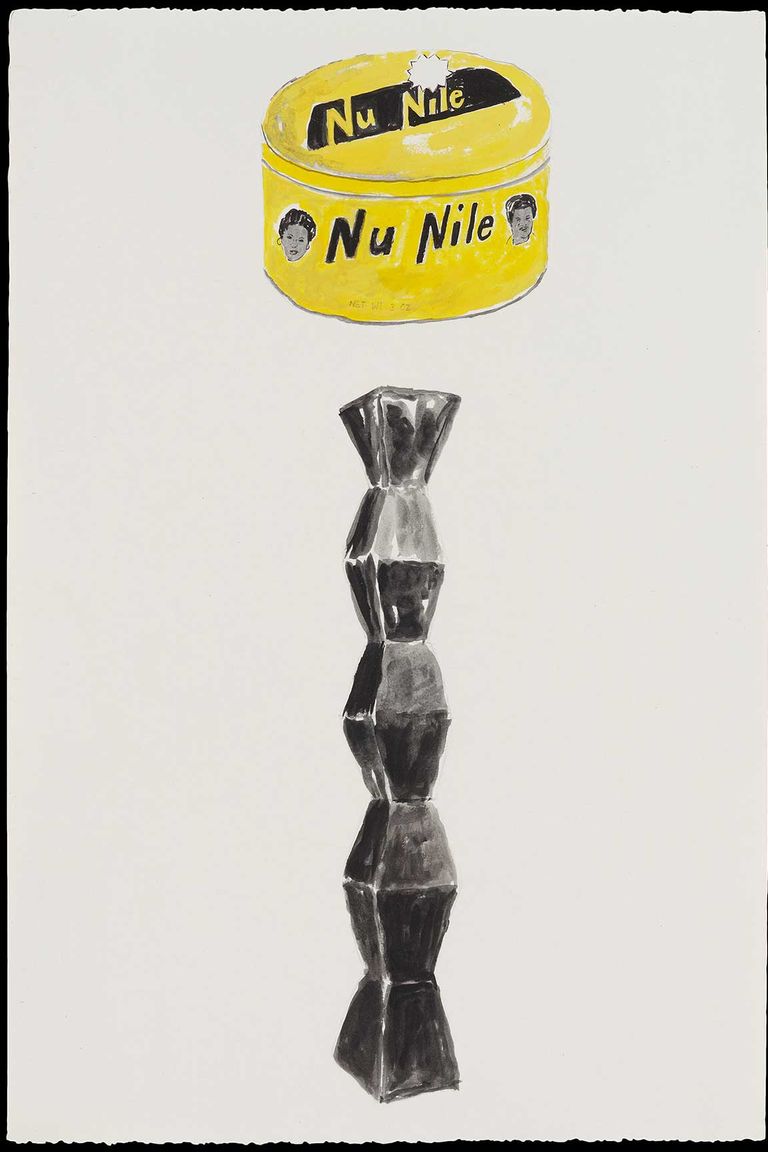

Glenn Ligon, Endless Column/Nu Nile (Yellow), 1985; Synthetic polymer, ink and graphite on paper; 22-1/8 x 15-1/4 in.

Glenn Ligon, The Cock/Nu Nile, 1985; Synthetic polymer, ink and graphite on paper; 22-1/8 x 15-1/4 in.

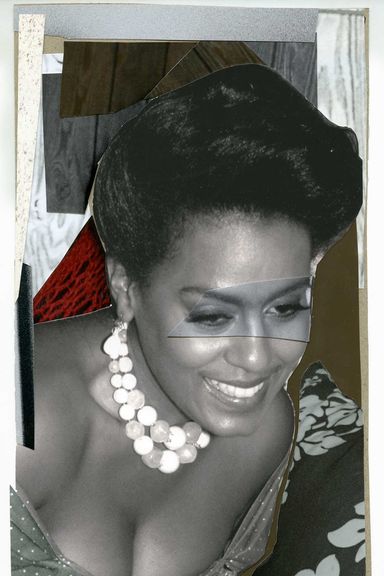

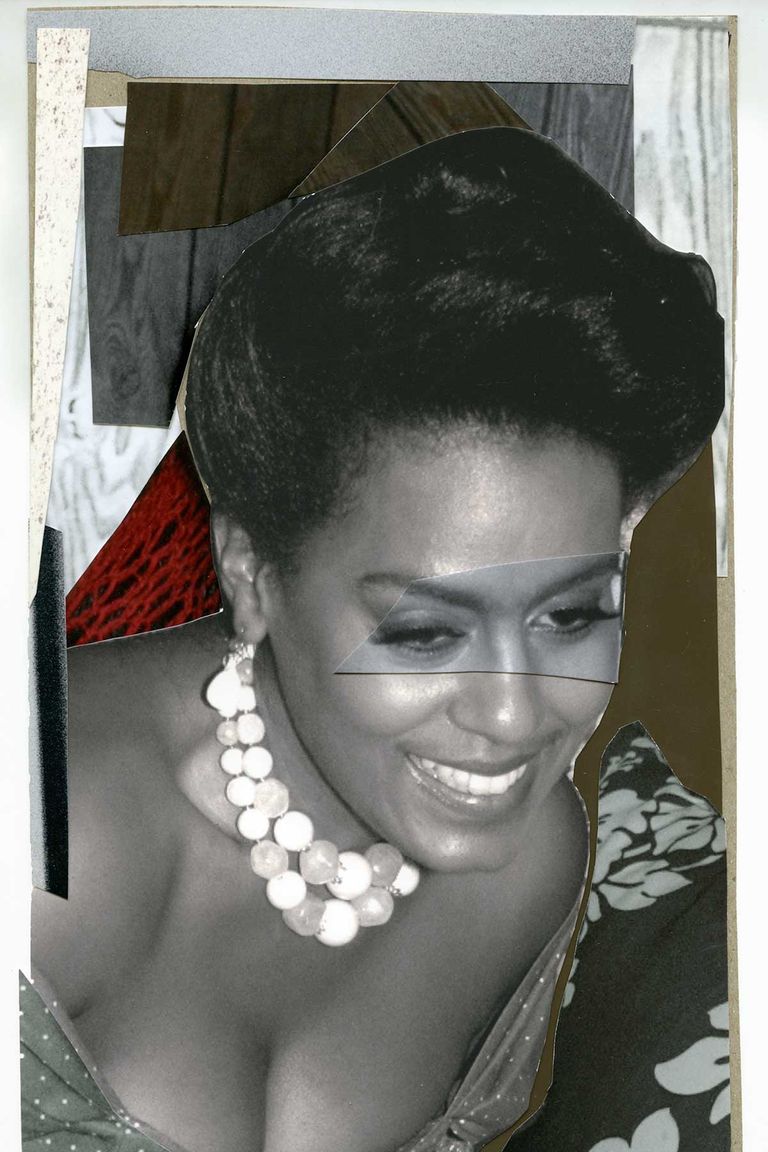

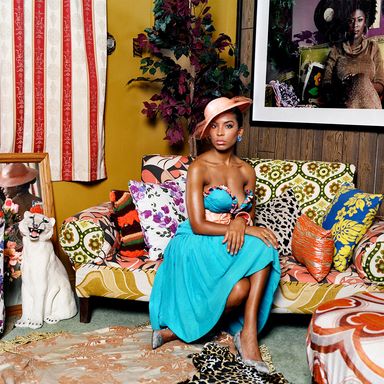

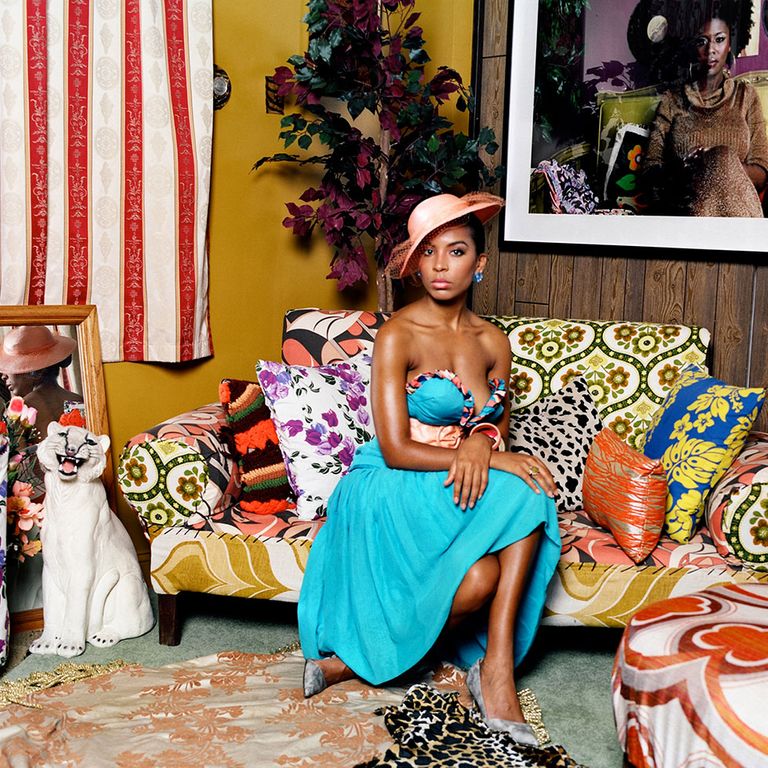

Mickalene Thomas, Clarivel Right, 2013; Color photograph and paper collage on archival board; 11-1/2 x 7-1/4 in.

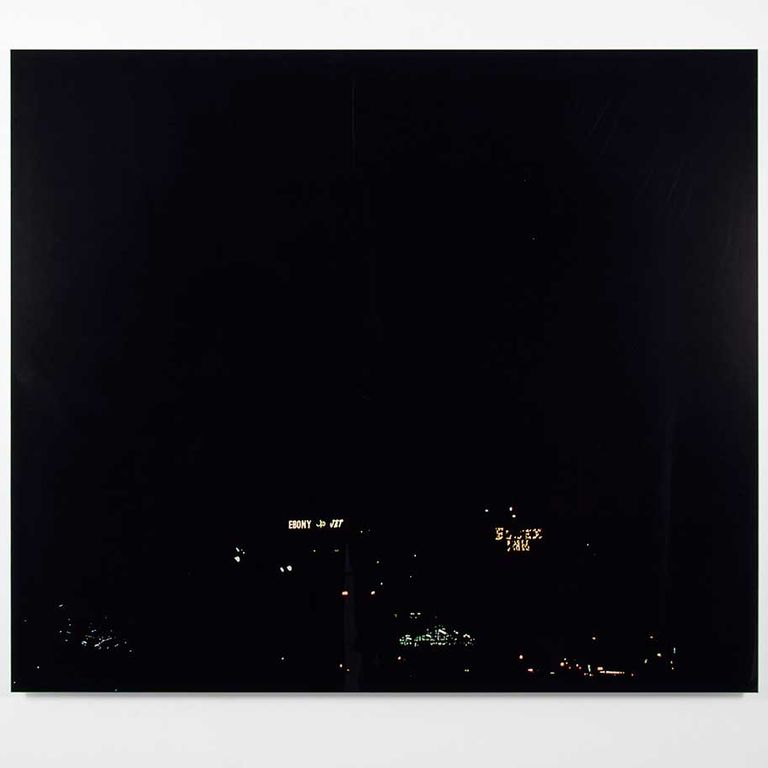

Kerry James Marshall, Black, 2002; Inkjet print on paper; 49-3/5 x 42-9/10 in.

Mickalene Thomas, Portrait of Lili in Color, 2008; Color photograph in custom-built wood frame; 10.5 x 11.5 x 1.75 inches

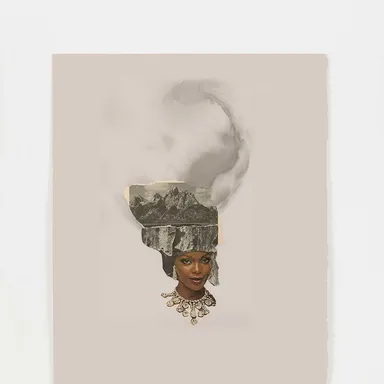

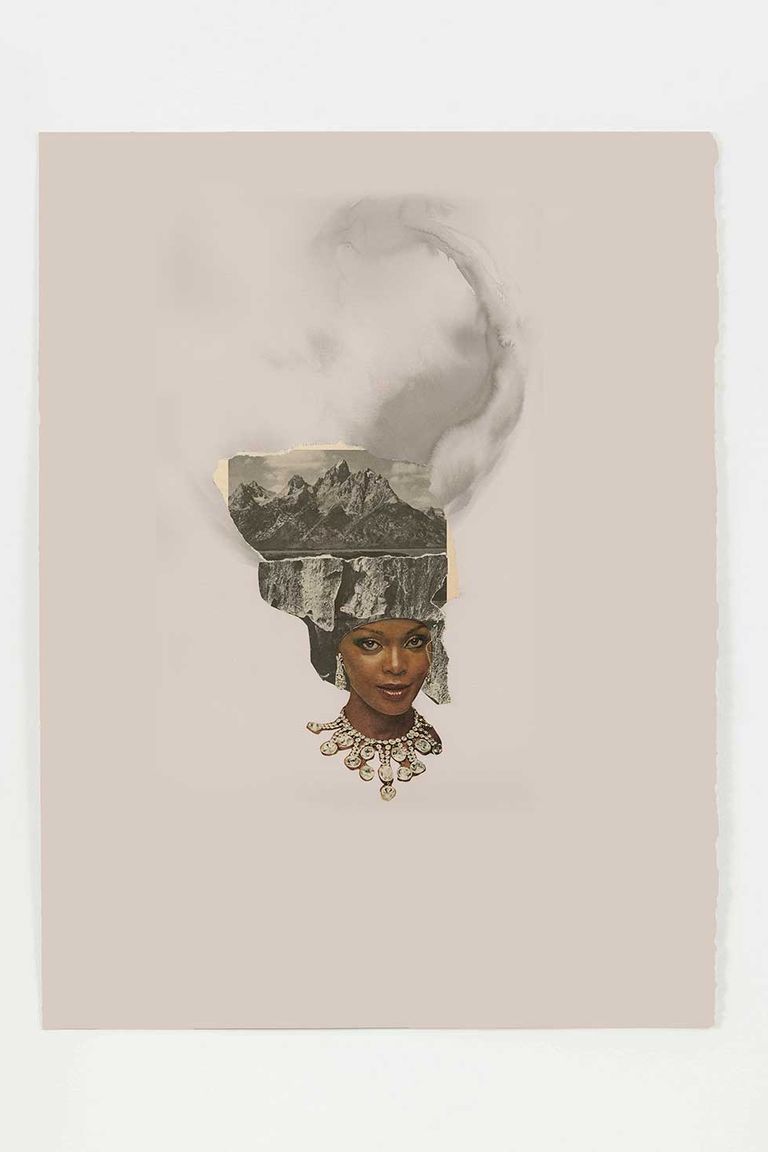

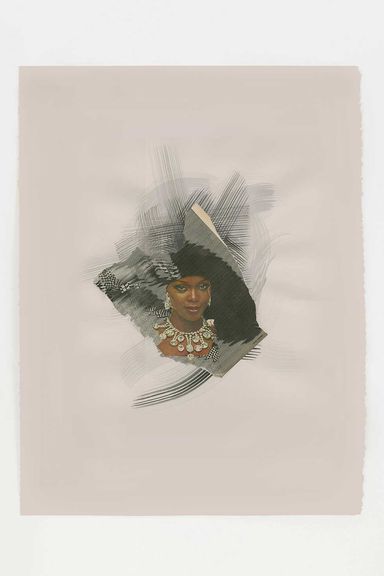

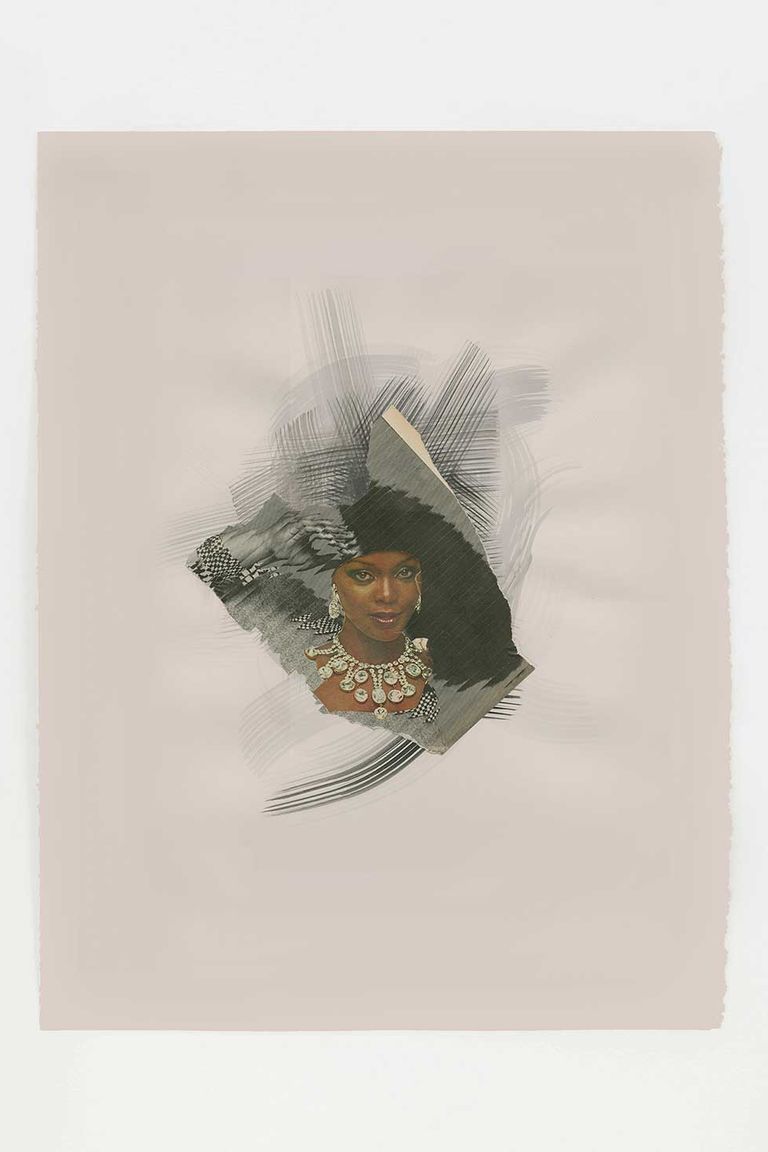

Lorna Simpson; “Riunite & Ice” Collage #1, 2014; Collage and ink on paper; 30 x 22 in.

Photo: Daniel PerezLorna Simpson, “Riunite & Ice” Collage #6, 2014; Collage and ink on paper; 30 x 22 in.

Photo: Daniel PerezLorna Simpson, “Riunite & Ice” Collage #8, 2014; Collage and ink on paper; 30 x 22 in.

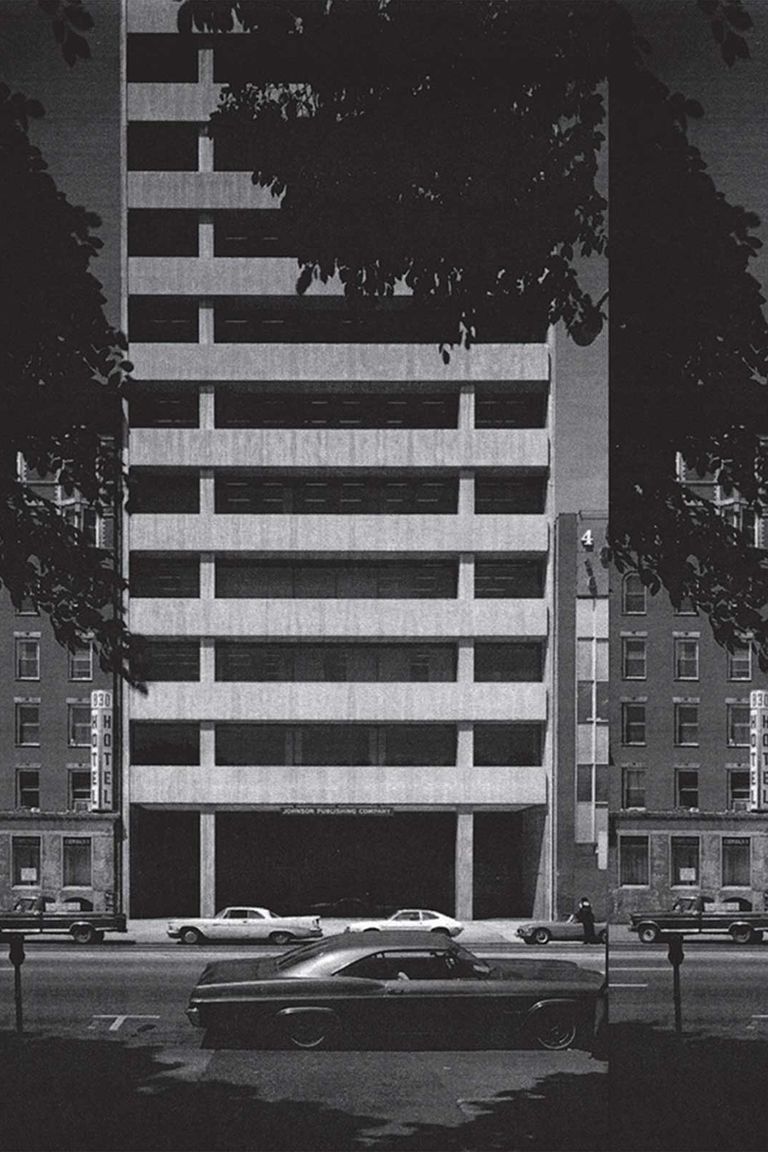

Photo: Daniel PerezMartine Syms, Johnson Publishing Company Building, 1971, 2013; Altered archival photograph; 18 x 24 in.

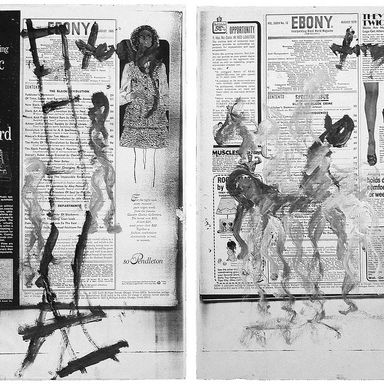

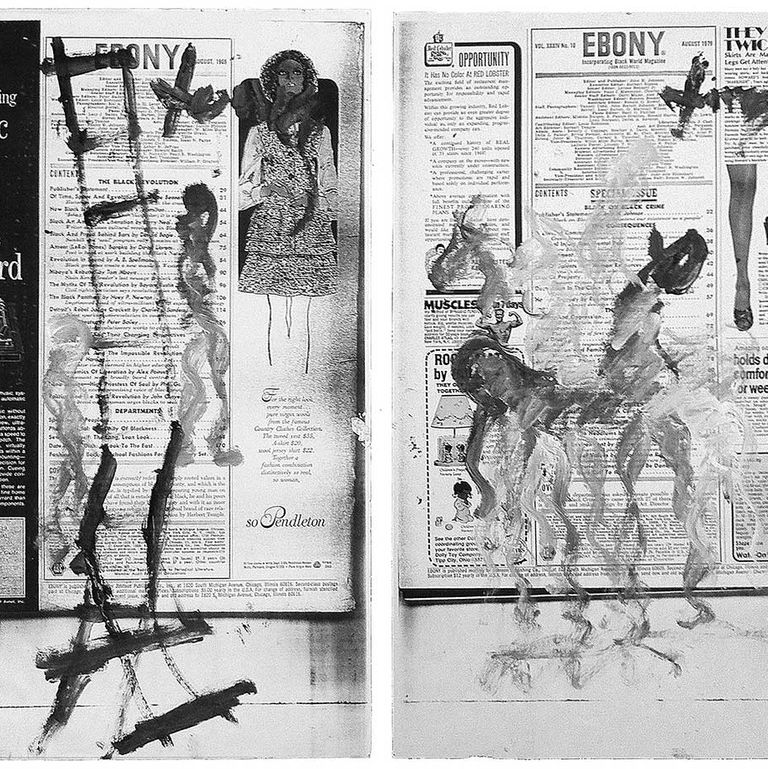

Purvis Young, Horses, Figures and Railroad Tracks on Ebony, c. 1994; Paint on paper; 17 x 11 in., diptych