Midway on her life’s journey, Cheryl Strayed found herself in dark woods. Or a quarter-way, really: At the age of 26, motherless, divorced, dabbling in heroin, adrift from her stepfather and siblings and her own former self, Strayed made her way to California, hoisted a backpack, and set off to hike 1,100 miles in the wilderness, from the Mojave Desert to a place on the Oregon-Washington border called Bridge of the Gods.

Nine days after she finished, she met a man in a Tex-Mex joint in Portland. They got married. They had two kids. Strayed wrote Torch, a semi-autobiographical novel that was quietly but kindly received. She wrote essays. She wrote, anonymously, “Dear Sugar,” the cult-favorite advice column of the online literary magazine The Rumpus. Then, in 2012, 17 years after she stepped back into civilization, she published a memoir about her time in the wilderness: Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail.

By that point, Strayed really was midway through her life, and it suddenly went a little berserk. The New York Times critic Dwight Garner described weeping over Wild, called it “loose and sexy and dark,” and named it one of the ten best books of the year. Equally passionate responses poured in from places as different as Outside Magazine and Vogue. Oprah picked it to revive her book club, on hiatus the previous two years. It held the No. 1 spot on the Times’ best-seller list for seven weeks, was translated into 32 languages, and sold some 1.75 million copies. Reese Witherspoon optioned it, with the intention of both producing it and starring as Strayed. She did; the movie opens this week.

I read Wild when it was first published, and I have been watching its ascent with surprise ever since. People love to read about outdoor extremis and debacle, à la Into Thin Air, but books about nature in which nothing goes terribly wrong do not normally attract millions of fans. Moreover, there is a kernel of genuine radicalism in Wild — and radicalism, by definition, does not appeal to the mainstream. Outside of slave narratives and horror fiction, adult American literature contains very few accounts of a woman alone in the woods. Yet Wild is the story of a woman who voluntarily takes leave of society and sustains herself outdoors, without the protection of a man, or, for that matter, of mankind. It is the story of a woman who does something physically demanding day after day, of her own free will, and succeeds at it. It is the story of a working-class woman and her mind — of what Strayed thought about in the three months she spent almost entirely alone. And it is a story that ends happily in the near-total absence of that conventional prerequisite for happy endings, romantic love.

On the face of it, that kind of tale risks being unpalatable to the American public, never mind wildly popular. That Wild succeeded anyway is an achievement, and an instructive one. In a culture with profoundly ambivalent feelings about independent women, it is not always clear what kind of adventures we will be lauded for undertaking, nor what kind of tales we will be lauded for telling. So why did so many people fall in love with Strayed and her story?

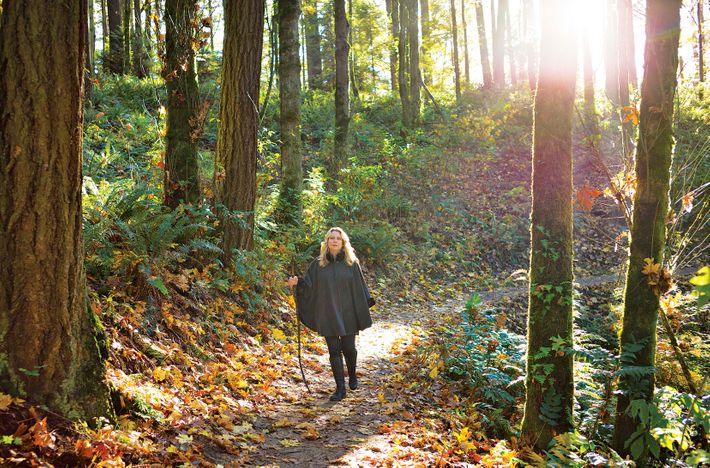

Cheryl Strayed touches a slate-gray band on her wrist. “My Fitbit,” she says. “We’re going to get our 10,000 steps.” Strayed and I are heading out for a stroll in Portland, Oregon, in the kind of weather for which that city is famous: not raining, but not not-raining, and certainly not certainly-not-going-to-rain. Strayed is undeterred, either because she’s lived here for nearly two decades, or because she once walked for 94 days in every conceivable meteorological condition, or because she really wants those 10,000 steps. She is wearing jeans and hiking boots — the lightweight kind that work for bumming around a city, or anyway around this city — and no coat, and the Fitbit.

“I’m obsessed with it,” she says of this last item. “I was so glad when you said you wanted to walk.” (I had proposed a hike, for obvious reasons, but even for Strayed, the weather forecast was a bit bleak for that.) “My favorite thing to do when I get together with my girlfriends is to go for a walk. I’m always like, ‘Can we go for a walk, can we go for a walk?’ and they’re like, ‘Let’s get a drink.’ I love to drink, don’t get me wrong, but I want to walk.”

Why is “pedestrian,” as an adjective, insulting? Walking is the pace most conducive to observation and conversation: a human pace, a good way to think through the world. Strayed and I amble along, talking about her upcoming projects — she has sold her next two books, a novel and another memoir, both as yet unwritten — and about her children: a son, 10, and a daughter, 9, who plays her own younger self in the movie. We pass the ghost of the restaurant where she met her husband, a documentary filmmaker. (It closed at the beginning of this year.) We pass the house where Strayed and her family lived while she was finishing Wild: a modest, pleasant, Arts-and-Crafts-style home whose white trim, she informs me, was purple during her tenure. We pass one of Portland’s oldest cemeteries, then double back and go in. It is called the Lone Fir, but there are trees everywhere, the tombstones below like an understory. The path is covered in the yellow fans of ginkgo leaves. It is continuing, so far, to not rain. “I love this place,” Strayed says. “Isn’t it beautiful?”

Strayed was born far from here, in central Pennsylvania, the second of three children. Her father was abusive. Her mother was hardworking, optimistic, patient with adversity, vocal and unconditional in her love for her kids. When Strayed was 5, the family moved to Minnesota; the next year, her mother left her father. Eventually she remarried, this time to a man who doted on the family and helped build them a home in rural northern Minnesota. Strayed graduated from high school, went to the University of Minnesota, fell in love, and got married while still a student. Her mother, who had missed out on higher education earlier in life, enrolled in college when Strayed did. She startled her daughter by earning straight A’s, then stunned her by getting diagnosed with lung cancer. She died just 49 days later, a 45-year-old senior in college, two classes shy of graduation.

Strayed herself, also a senior at the time, would not graduate for another six years. Devastated by her mother’s death, she lost interest in her coursework. She started having affairs. One of the men she slept with got her pregnant. That same man introduced her to heroin. She and her husband got divorced. In effect, she and herself got divorced. After four years of increasingly destructive estrangement from the person she’d been before her mother died, she went to an outdoors store, bought a guide to hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, and set out to walk back to life.

“Is that a tombstone that looks like a tree?” Strayed asks. It is: In the southeast corner of the cemetery, not far off the path, there’s a headstone designed to resemble a stump, made more convincing by the layer of moss growing over it. “It’s kind of spooky, isn’t it?” Strayed asks. “It reminds me of The Wizard of Oz when the trees come to life.” We try to make out the inscription. “Here rests a woodsman of the world,” Strayed reads aloud. Martin Hansen, born 1861, died we can’t quite tell, 19-something. Only the first few words of the lines below are legible: A precious … A voice … A place …

Time works strange changes on the world. Some things grow dull, some grow wild, some erode past legibility. After Strayed saved her life, after she told her story, after that story became a best seller, strangers started asking her what she would say if she could go back in time and talk to her mother. “It used to be something sentimental like, ‘I love you, Mom, thank you,’ ” Strayed says. “Now it’s like, ‘Laura Dern is playing you in a fucking movie!’”

That would constitute a dramatic development in anyone’s life, or afterlife, but Strayed downplays the impact Wild’s success has had on her and her family. “I have not changed at all,” she says, “and my life hasn’t changed except in one regard, which is that I have enough money to pay my bills for the first time ever.”

This is an understatement, but it is one with a context: Strayed’s life had already altered so much by the time she wrote Wild that any further changes struck her as comparatively minor. As she describes in the book, Strayed grew up on the economic margins. Her mother cleaned buildings and waited tables to support the family. The leanest years ended when she remarried, but money remained tight, and the home in rural Minnesota lacked indoor plumbing. Strayed worked from adolescence onward to put herself through college and, later, an M.F.A. program in fiction at Syracuse University.

That education, in turn, put Strayed into an entirely different universe. “I do not share the same socioeconomic class as my siblings or my stepfather,” she says. “I have an entirely different life and world and orbit and vernacular and cultural reference points and magazine subscriptions — I mean, everything.” Before Wild came out, Strayed and her husband were, in her words, “dead broke,” but they each had a master’s of fine arts. “We were the impoverished elite,” she said, “and that is so different from actually being poor.” It is so different, in fact, that her subsequent migration to the affluent elite paled by comparison.

Still, the success of Wild has demonstrably changed Strayed’s life. She bought a second home — a cabin in the mountains east of Portland — and has traveled all over the world; last year, she and her family vacationed with Oprah in Hawaii. “I try to tell my kids this isn’t normal,” Strayed says wryly. She wants to give them the experiences she didn’t get to have, but she also wants them to know how fortunate they are — she recently gave her son a talking-to after he disparaged the school lunches she herself grew up eating — and she hopes to pass on some of what she did have growing up, such as a work ethic. “But you know,” she says, “some of that, you can’t replicate it. You can’t pretend you had to spend every summer of your teenage life working at the Dairy Queen when you actually get to go to camp in Vermont.” She laughs. “They are going to have a better life than me.”

We have a name for what Strayed experienced: the American Dream. With living-wage jobs declining and class stratification increasing, that dream is ever more elusive, but Strayed is among those who achieved it. Through hard work, higher education, and very little in the way of outside help, she raised herself out of poverty and into the middle class. Eventually, of course, she rose even higher, into the kind of glamour — text messages from Oprah — that even the American Dream can only dream of. But it is the basic bootstrapping from poverty to self-sufficiency that we observe in Wild, and that helps make its story so automatically appealing.

I don’t mean to suggest that Wild is fundamentally a rags-to-riches tale. It is not. But the book succeeded in part because of the way it fits into the prevailing stories we tell about three things: about class, about women, and about suffering. Those stories are not separable, of course. The American Dream, for instance, is a fantasy of self-reliance, but our culture is iffy on self-reliant women.

The way Wild handles that problem became most clear to me while watching the movie version. When Witherspoon first approached Strayed about making it, “she used really strong language,” Strayed says. “I took notes. She said, ‘I promise you I will get this movie made quickly, and I will protect you, and I will honor you, and I will make this a film that we are all proud of, and I will not turn you into some dumbass chick on the trail complaining about her muffin top.’”

Witherspoon kept those promises. As the star of Wild, she is grubby, unglamorous, and convincing. As a producer, she delivers a film that passes the famous Bechdel Test: At least two women talk to each other about something other than a man. In fact, it also passes a kind of Advanced Bechdel Test: A non-crazy woman talks to herself about something other than a man. Watching it, I realized that the closest analogue to Wild might be Gravity, the 2013 Alfonso Cuarón film. In it, Sandra Bullock plays Ryan Stone, a scientist on a NASA space shuttle who must find her way back to Earth after a debris strike destroys the shuttle and kills her colleagues. Gravity is fiction while Wild is a memoir, but both offer the experience — extraordinarily rare in popular culture — of watching a woman teach herself how to get from A to B under very difficult circumstances and entirely alone.

What struck me most, though, is the symmetry of the backstories in Wild and Gravity. Strayed sets out on her journey after the loss of her mother (and husband, stepfather, father, and childhood home), Stone after the loss of her 4-year-old daughter. (There is no Mr. Stone.) It is as if only the total destruction of the domestic sphere could justify a woman’s presence on such adventures. Or rather — since Strayed’s story is not fabricated — it is as if that destruction were necessary in order to secure the audience’s sympathy for a woman doing something risky and alone.

Granted, men, too, sometimes seek out extreme environments in response to psychic wounds, in life as well as in literature. But for them, the wound is optional; men are free to undertake an adventure without needing trauma (or anything else) to legitimize it. By contrast, a woman’s decision to detach herself from conventional society always requires justification. Women can, of course, go out exploring for pleasure or work or intellectual curiosity or the good of humanity or just for the hell of it — but we can’t count to ten before someone asks if we miss our family, or accuses us of abandoning our domestic obligations.

As a literary device, the destruction of the home front silences these concerns. But it has another advantage: It is universally familiar — not from stories about independent women but from stories about independent children. In real life, the death of a parent is an agonizing loss. But in fiction, that death, while nominally tragic, often marks the beginning of an adventure; it gives the hero the freedom, and sometimes the motive, to go explore an unfamiliar land. Mowgli in the jungle, Bambi in the forest, Huck on his raft, Dorothy in Oz: For any of these adventures to transpire, the parents must first be made to vanish. That is partly to stoke our sympathy for the protagonist. And it is partly because our culture believes — sanely enough — that, under normal circumstances, children should be watched over and keep close to home.

Our culture also believes, insanely enough, that much the same applies to women. No surprise, then, that successful accounts of wayfaring women also make use of this backstory. Strayed is a canny storyteller, conscious of deep-seated narrative structures and adept at deploying them. But she is nothing if not sincere, and she did not concoct or manipulate her past to make it more compelling. She didn’t have to. By terrible chance, the story of her life conforms to a tale we all already cherish. As in that early scene in Bambi that so reliably makes viewers cry, Strayed loses her mother in terrible fashion, and that loss leaves us rooting for her as she strikes out alone through the woods.

The year after Strayed backpacked the Pacific Crest Trail, the writer Bill Bryson backpacked the Appalachian Trail, the PCT’s East Coast counterpart. In A Walk in the Woods, his 1998 book about that experience, he discusses, among other things, the history of the U.S. Forest Service, strategies for surviving a bear attack, violence against women in the outdoors, and the impact on the wilderness of logging, agriculture, invasive species, and climate change.

Nothing like this appears in Wild. The book contains almost no ecology, botany, geology, or natural history, and Strayed makes little attempt to describe in any other terms the wilderness that, for three months, served as her home. This is not for want of aptitude. When she does choose to focus on her surroundings, Strayed can be original and astute. A bear on the trail is “as big as a refrigerator.” A llama she happens upon “smelled like burlap and morning breath.” A lizard on a rock “seemed to be doing push-ups. ‘Hello, lizard, I said.’” That is just right, both descriptively and emotionally: Somehow, all the good and surprising things in the wilderness call forth an instinct to greet them.

But, that lizard aside, Strayed is not in the business of introducing herself or her readers to the outdoors. When she was writing the book, she says, “my editor would always come back to me and say, ‘I want to see this, what are the plants, what does it look like?’ And I’d be like, ‘It’s just, you know, wilderness, okay?’”

As a genre, writing about the wilderness — nature writing — is a relatively recent phenomenon. It emerged, counterintuitively, during the Industrial Revolution, when everything about the rural past became an object of nostalgic interest, and nature came under threat for the first time in history. In response, people started forming a new set of relations with the natural world. Masses of amateur scientists began to observe, collect, and taxonomize it; proto-environmentalists began to sound the alarm about it; and Romantics began to romanticize it. Nature writing as we understand it today reflects, in varying degrees, all three of those traditions.

Strayed came to this body of work late — after she wrote Wild — and she does not identify with it. “It’s this educated white guy who spends a lot of time roaming around his properties,” she says, “plus usually a pretty intellectual, dry way of writing about the natural world. And we very seldom hear anything about the interior life.”

That last charge is not entirely fair (John Muir: “Going out, I found, was really going in”), and the middle one is a matter of taste. But the first one is inarguable. For a long time, most nature writers were wealthy white property owners, and walking alone outdoors was not an option for women. (Men get to be flâneurs, those peripatetic observers of urban life, but a woman walking the streets has a notably different connotation. And the reputation of women in the woods is scarcely better — the most famous examples being, after all, witches.) Moreover, women were not regarded as credible chroniclers of their surroundings, a status extended automatically to educated white men. “The authoritative voice that white men of privilege have assumed, and have also been granted — that is the difference between their voice and mine,” Strayed says. “I make no attempt to be the authority.”

Instead, Strayed belongs to a different and more demotic group of people who walk countless miles outside and alone. These are the religious pilgrims: the Muslim walking to Mecca, the Buddhist to Bodh Gaya, the Hindu to Puri, the Catholic to Lourdes. (Ancient Jews made pilgrimages to the Temple at Jerusalem, but that was destroyed 2,000 years ago. More modern Jews do not traditionally walk, possibly because, traditionally, we flee. This could be a generalizable truth: People in diaspora stay put when they can.) Religious pilgrims walk outdoors, but their fundamental journey is inward, undertaken to improve the state of their soul. So, too, with Strayed. The subtitle of Bill Bryson’s book is Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail. The subtitle of hers is From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail.

Like Dante, then, Strayed is on a spiritual journey, beginning in damnation, bound for deliverance. That makes Wild a redemption narrative — and that, in turn, helps explain its popularity, because redemption narratives are some of the oldest, most compelling, and most ubiquitous stories we have. We enshrine nature writing in the canon — you were probably assigned Thoreau and Emerson et al. in high school — but it is redemption narratives that dominate our culture. Among other things, you can hear them in religious services all across the land and in AA meetings every day of the week.

Wild embodies this ancient story. Or, more precisely, it embodies the contemporary American version thereof, where the course is not from sin to salvation but from trauma to transformation: I was abject, dysfunctional, and emotionally shattered, but now I see. This version has more train-wreck allure than the traditional one (being a mess is generally more spectacular than merely being an unbeliever), and it is also more inclusive. Identifying with it requires no particular faith, beyond the faith that a bad life can get better.

The American redemption narrative, then, is entertaining, accessible, and privately comforting. And, in the case of Wild, it is culturally comforting as well. Before Strayed sets off on her journey, she embodies much of what America fears about young lower-class women: She does drugs, sleeps around, gets an abortion. Eleven hundred miles and 315 pages later, she has sobered up, sworn off the one-night stands, and become as wholesome and appealing as the girl next door.

Now, intentionally or otherwise, Strayed is in the business of telling other people that their lives, too, can be redeemed. As “Dear Sugar,” the advice columnist, she acquired a throng of impassioned followers who devoured and discussed her every line. Uncharacteristically, for an internet forum, the dominant tone was identification (“Someone finally gets me”), illumination (“I finally get it”), and gratitude bordering on reverence. In the introduction to Tiny Beautiful Things, a 2012 collection of Strayed’s columns, the writer Steve Almond noted that “people come to her in real pain and she ministers to them.” Even the form of those columns — question, anecdote, illumination, benediction — owes more to the homiletic tradition than to Ann Landers. Somewhere along the line, the secular pilgrim turned into a secular priest.

Wild is not a book of advice, but it was received in much this same spirit. Its readership has surpassed not only that of her last book but that of books, period — “All these people who don’t even read have read Wild,” Strayed says — and fans show up at her events in a fervor to meet her. “I never imagined Wild would be read as inspirational,” Strayed says — never mind that her writing had been described as such for two years before the memoir came out. “But it’s the No. 1 thing people say to me now: ‘I was so inspired by your book.’”

Strayed attributes this reaction to having captured, in Wild, something shared and profound: “Not just meaning for my own life, but also universal meaning.” In other words, like the masculine nature writers she rejects, Strayed lays claim to universal truths. The distinction is that old familiar one: They assert the facts of the outer world, she of the inner one. To write Wild, Strayed says, she had to determine “what’s deeply true about my experience of grief, my experience of journey, my experience of solitude, my experience of reckless behavior. Once you get to that, when you really tell the truth, you’re actually speaking a universal language. I really believe that.” So many people dismiss memoirs as narcissistic — and they are, she says, “if they stop at the surface truth. But if you go into that deep truth, you aren’t talking about yourself. You are talking about what it is to be human.”

In John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, published in 1678, a young man named Christian leaves the City of Destruction and sets out on a journey. His travels take him across the Slough of Despond, up Hill Difficulty, through the Valley of Humiliation — and so on, until finally he crosses the River of Death and is welcomed in Celestial City.

Strayed’s experience on the Pacific Crest Trail was not allegorical. If Fitbits had existed at the time, she would have logged something on the order of 2.2 million steps. And yet her physical journey sometimes disappears under the metaphorical load it must bear, so perfectly is it matched to the spiritual one, and so seldom is the outer world shown to us on any other terms. Her passage begins in the desert and ends at the Bridge of the Gods; she writes, of her backpack, that “I’d come to accept that it was my burden to bear.” Like Strayed’s last name — which she bestowed upon herself after her mother’s death and the dissolution of her first marriage — her journey can feel, at times, a little too apt, a little too laden with meaning.

Wild, in short, is not a subtle book. Strayed is like a confessional Nick Adams; she vanishes into the woods not to avoid saying anything but in order to say everything. Her most telling stylistic tic is the single-line paragraph, which serves to render portentous whatever sentiment is at hand. (During her second day on the trail: “I was in entirely new terrain.” After rereading a favorite work by Adrienne Rich: “It was a poem called ‘Power.’ ”) Even her negative statements can have a strangely uplifted aspect. The line “God was a ruthless bitch” seems to arrive already anticipating its audience reaction: Right on, sister, you go, girl, amen. Her most famous line, “Write like a motherfucker,” from one of her “Dear Sugar” columns, has become an informal motto among her fans. You can get it emblazoned on coffee mugs and T-shirts.

This emotional cheerleading is surely another reason for Strayed’s popular success. Life itself is none too subtle sometimes either — try grief — and our culture has never lacked the appetite for fighting sentiment with sentiment. Strayed, who is smart and blunt and funny, wields it better than most. But one man’s cure is another man’s poison, and I found myself put off by the overtly inspirational aspects of Wild.

But I also found that they made me think of something Strayed wrote about her mother. “She was optimistic to an annoying degree,” she fumes at one point, “given to saying those stupid things: We’re not poor because we’re rich in love! or When one door closes, another one opens up! Which always, for a reason I couldn’t quite pin down, made me want to throttle her, even when she was dying.”

Anyone who has ever been driven irrationally batty by some benign quirk of a mother will identify with that passage. But what struck me most about it is that Strayed has done what so many of us do: unwittingly became a version of her mother, right down to the qualities that irked her. When I mentioned that she was lucky to have had such a positive experience with the movie version of Wild, she said, “I find that when I’m vulnerable, when I take risks emotionally, when I decide to take an open stance instead of a closed stance, when I offer my hands instead of close them into fists, good things come.” Possibly this would annoy Strayed’s daughter. Certainly on the page it would have annoyed me. But in person, I was struck only by how absolutely sincere she was; and also by the fact that she had a point.

And, finally, I was struck by how Strayed had become her mother in another way. As we were walking through the cemetery, she told me that she does not believe in God in any conventional sense. Instead, her faith amounts to a radical acceptance of the world as it is. “The divinity in life is about not just grace, not just beauty, not just birth,” she said, “but also all the ugly, gnarly, brutal, ruthless things.”

That might be a theology, but it sounds like something else: mother love. To accept life unconditionally, to be undeterred by any amount of sorrow it might bring your way, to cherish it and find it worthy even at its most difficult and cruel: Thus do parents, in the ideal, love their children. Thus did Strayed’s mother love her.

Wild succeeded in part because it channels so many of our oldest and most broadly shared stories. Strayed is an orphan cast out into the world; she is a bootstrapper lifting herself out of poverty; she is a pilgrim walking to salvation; she is even a pioneer, going West to grow up with the country. But her book’s deepest power might come from a different and even more time-honored journey: that of a daughter becoming a mother — in this case, implicitly, to us all. The journey Strayed recounts in Wild culminates when she learns to love herself as her mother no longer can. And that kind of love — extravagant, unwavering, undiminishable — is what she offers to her readers, and urges us to find in ourselves.

*This article appears in the December 1, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.