Hollywood has never made a great movie about North Korea, and now itÔÇÖs uncertain whether it ever will. It was close, though. Unlike the mediocre Rogen/Franco comedy at the center of this hurricane, Pyongyang,┬áthe planned film adaptation of cartoonist Guy DelisleÔÇÖs nonfiction comic book Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea, could have been a work of art. But now itÔÇÖs lost to us forever.

Director Gore Verbinski was helming the project, and Steve Conrad had written the screenplay. New Regency was producing it. It was to star Steve Carell as an unusual protagonist based on Delisle: an animator visiting one of North KoreaÔÇÖs little-discussed animation studios. What little we know about the movie suggests Verbinski and Conrad had sexed up the plot from DelisleÔÇÖs original nonfiction narrative: The Wrap reported it was to be ÔÇ£a paranoid thriller about a WesternerÔÇÖs experiences working in North Korea for a yearÔÇØ; the book actually has very little narrative and merely recounts DelisleÔÇÖs work and wanderings in the titular capital of North Korea for a couple of months. So who knows? Maybe Verbinski and Conrad would have watered down the beauty of DelisleÔÇÖs original work and turned it into a generic foreigner-in-trouble flick.

But the source material is so rich, masterful, and unique that one canÔÇÖt help thinking we lost our shot at something beautiful. Pyongyang is one of the most beloved graphic novels of the past 20 years (note: the term ÔÇ£graphic novelÔÇØ here doesnÔÇÖt refer to a novel, per se, given that the story was a nonfiction memoir; however, thereÔÇÖs no good replacement term), and deservedly so.

Where other tales of North Korea (admirably) shout about the countryÔÇÖs horrors and international belligerence, Pyongyang is quiet and observant. Where other writers and documentarians have met resistance from regime officials, Delisle simply came for a job and was therefore granted uncommon access and treatment. Where other storytellers have portrayed themselves as muckraking heroes (or not portrayed themselves at all), Delisle depicted himself acting the way most of us would: playing by the rules, regretting dumb things he blurted out, drinking too much, feeling lonely, and often being an irritating jerk to those around him.

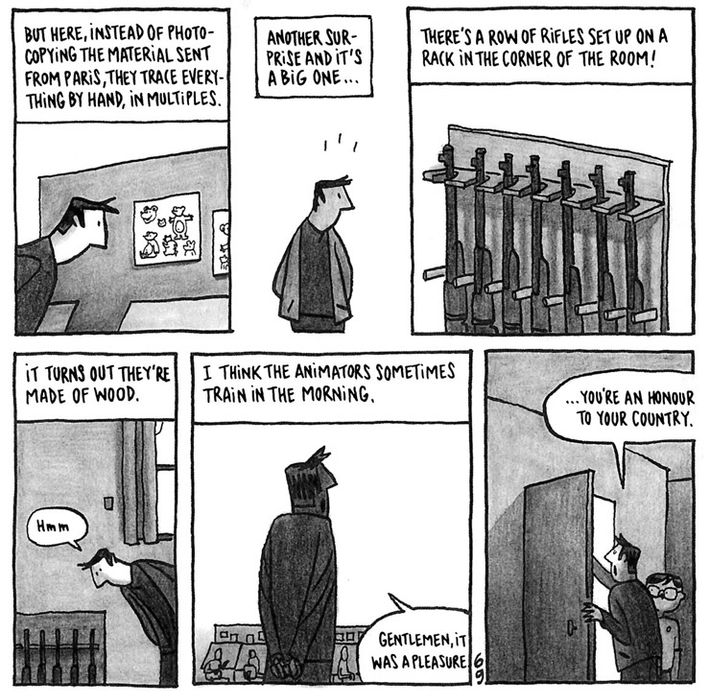

The book is light on plot and heavy on observation. In 2001, Delisle ÔÇö a Canadian┬áQu├®b├®cois artist and animator ÔÇö gets a two-month visa to stay in Pyongyang. He spends his workdays at SEK Studio, an animation house that does outsourced grunt work for some Western production companies (the U.S. isnÔÇÖt supposed to use North Korean labor for its animation, but there have been allegations that studios as big as Disney have gotten covert work done there). He struggles to communicate with the animators, who are incompetent but friendly. Their interactions are fascinatingly non-condescending: Delisle doesnÔÇÖt act like an enlightened Western savior, but instead just a frustrated colleague.

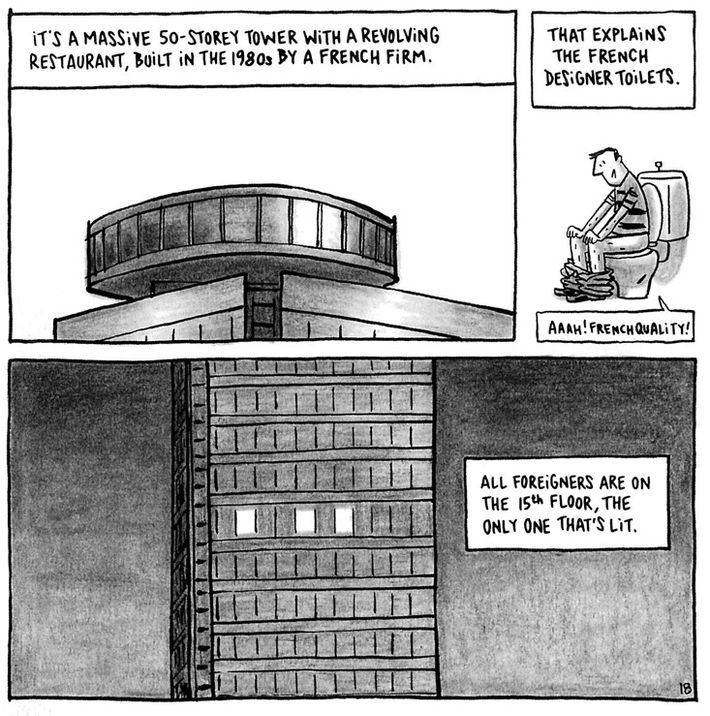

Handlers and translators follow him around, as is common for foreign visitors, but he manages to shake them off for a brief trip to a harmless-but-off-limits train station. HeÔÇÖs only mildly chastised, and for the most part, the men assigned to follow him contendedly take him to various major sights: the massive statue of Kim Il-sung, a museum declaring North KoreaÔÇÖs great relations with all peoples of the world, the massive pyramidal hotel that (if itÔÇÖs ever finished) will be the largest hotel in Asia, and so on. He hangs with the small group of other foreigners who are there for various tasks: an Austrian aid worker, a Middle Eastern diplomat, Chinese tourists, and the like. It often feels like a dystopian Lost in Translation, made even more fascinating than that movie because DelisleÔÇÖs narrative is so calm and personal.

ÔÇ£I have bits of journalism in it because I have to convey information in the book, like how they distribute the food and this and this, but itÔÇÖs a really small part of the book,ÔÇØ Delisle told the Comics Journal in 2011. (He declined my request for an interview.) ÔÇ£The rest is more about everyday feelings and the impressions I had about the people. IÔÇÖm much more of a traveler than a journalist and much more of a daydreamer. The best description I can make of my book is itÔÇÖs a big postcard I would send to my family. In that postcard I put everything I find funny, strange, interesting and I want to explain a few things, but for me itÔÇÖs very far from journalism.ÔÇØ

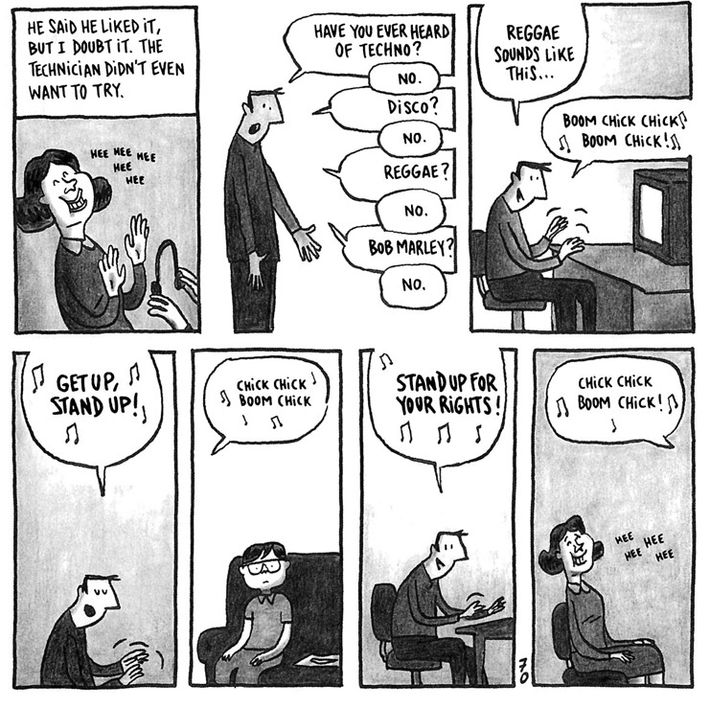

Instead, we get one illuminating vignette after another. ThereÔÇÖs the time a smiling SEK technician plays some North Korean pop songs, which Delisle describes as ÔÇ£a cross between a national anthem and the theme song of a childrenÔÇÖs show ÔǪ like a Barney remix of ÔÇÿGod Save the QueenÔÇÖ or ÔÇÿOh Canada.ÔÇÖÔÇØ Or the time he stays out too late and is forced to walk home in near-total darkness (Pyongyang shuts off its streetlights after dark, making the metropolis eerily postapocalyptic), but finds his way when he comes upon the only lit object he can find: a massive painting of Kim Il-sung. (How great would that have looked on film?) Or the time Delisle and a fellow foreign animator make up a song about their translator to the tune of the Captain Planet theme. The list goes on. Everything is elegantly told and compellingly specific.

There are occasional grand observations about North Korea, but theyÔÇÖre blessedly few and far between. Instead of being self-righteous, Delisle writes himself as a bit of a dick. While touring a museum devoted to tortures inflicted by Japanese and Americans, he idly fantasizes about screwing the tour guide (ÔÇ£I think up a few tortures of my own that I wouldnÔÇÖt mind inflicting on herÔÇØ). He sees a poorly drawn animation of a cartoon bear waving good-bye and cackles about how terrible it is, right in front of the ashamed and confused director (he tells the man that the bear looks like heÔÇÖs ÔÇ£giving a salute while getting an electric shock! Ha ha ha ha! Yes, ha ha ha! ThatÔÇÖs exactly it, an electric shock! Dzzt! Dzzt!ÔÇØ). How wonderful it could have been to see Steve Carell, that master of improper behavior, playing such an awkwardly human protagonist.

But weÔÇÖll never see Carell step into DelisleÔÇÖs shoes. In a statement, Verbinski said Fox ÔÇö the movieÔÇÖs distributor ÔÇö had refused to distribute it under any circumstances. New Regency was ÔÇ£forced to shut the film down.ÔÇØ

As Verbinski told Deadline: ÔÇ£I find it ironic that fear is eliminating the possibility to tell stories that depict our ability to overcome fear.ÔÇØ DelisleÔÇÖs original book wasnÔÇÖt about overcoming fear, so maybe we can take solace in thinking weÔÇÖve avoided a movie that ruined DelisleÔÇÖs original vision. But thatÔÇÖs cold comfort. A story like DelisleÔÇÖs ÔÇö no matter how warped it might have become ÔÇö needs to be told, if weÔÇÖre to understand the bizarre and awful country that has become abruptly central to film history. Instead, all weÔÇÖll be left with is pirated copies of The Interview.