Here’s How Miranda July Dressed in the ’90s

Miranda July’s novel The First Bad Man will be published on January 13. In conjunction with its release, the artist-filmmaker-actress-writer and more has produced 40 objects from the novel in real life. The items are personal and feminine — ranging from brassieres, bikinis, high heels, and beauty products — and all are intended to belong to July’s main protagonist, Cheryl, a woman who lives alone with her own obsessions. And you can buy them, until the book’s launch, at the First Bad Man store.

In July, she developed an app called Somebody, which melded performance art with technology, with Prada. The app is currently included in the Yerba Buena Arts Center exhibition “Alien She,” which is a thoughtful look back at the riot grrrl movement. The show, titled after the Bikini Kill anthem, traces the influence riot grrrl had on seven women artists across several genres. Most notably, it includes queer artists Tammy Rae Carland and L.J. Roberts, who presented new or rarely seen before works. July has made it clear in interviews that she is not, in fact, a riot grrrl. She found herself in Portland during the early 1990s, when her best friend, Johanna Fateman, the founding member of Le Tigre, moved to the city and befriended Bikini Kill front woman Kathleen Hanna. But the movement’s influence on July is obvious and profound. And she does champion younger women writers, especially Rookie founder Tavi Gevinson and Girls creator Lena Dunham, whose work pushes against boundaries riot grrrl articulated decades ago. So instead of discussing July’s new novel, we thought we’d ask her to share her thoughts on femininity and personhood in light of the “Alien She” exhibition.

How did you dress in the ‘90s? And what are your thoughts on how you presented yourself?

I have some thoughts on dressing during the time of riot grrrl. It’s safe to say — as time goes on — that that was a very specific era. I knew only women, and I only knew women who were punk and in bands. I was actually going to write about this for the Women in Clothes book. Looking at pictures from that time, my main goal, besides looking great, which I thought I did by my own standards, was that you should look at me and not have any point of reference. I should be disorienting.

One of my “trademarks” was wearing tights over my shoes, which wore them out quickly but looked amazing and created a very long leg. Wearing eyeliner on my mouth, a mark on either side of my mouth, it sounds a little big like the Joker [from Batman], but it wasn’t reminiscent of that, it was subtler; in pictures it looks like I have a wide mouth. Kind of like Karen Black. Then I had white, white hair, which I powdered with talcum powder so it was kind of Marie Antoinette in a very dirty sense. Often I had a fake wound or two, I had these rubber wounds, and I would just slap one on my neck. This is on top of the standard Drum Majorette uniform top, maybe a bathing suit under as clothes, and then like a little faux-fur coat that was actually for a 3-year-old but I had embroidered in sequins on the back “I’m Doing Fine,” in case anyone was wondering, which nobody was.

I think in some ways what was going on there was I knew I wasn’t pretty enough to actually get my power that way. I was more acutely aware of that then than at any other time. I was moving in the world as a sexual entity and realizing I wasn’t going to get my power that way. The important thing was to exist and dress in a way where no one would be able to know what the point of reference was when they saw me, so they would feel so disoriented that they could only compare me to myself. I really threw my energy into that. I now see that I did that with my work, too.

I knew I couldn’t play in a band. I knew from a young age that I wasn’t gifted musically, I couldn’t sing. I wasn’t going to be good at anything measurable. I think its interesting, the choices born of insecurity, the sense of what’s missing. Young women who want advice are often so sure it’s stuff that they’re good at that’s going to be the way forward, and in fact it could be the thing that’s missing that defines their specific path and makes them different from anyone else.

And is that insecurity what informed your own trajectory?

Of course it wasn’t just insecurity. I loved to perform also. That’s where my ideas went. It was also a lo-fi way to make movies, and I was curious about that. It didn’t feel accessible to me initially. It’s interesting, I think, there’s a certain strength in working across mediums. It’s like not putting your eggs in one basket, and not feeling vulnerable to any one market or any one critic or your own feeling about that medium. I suppose I’ve gained the confidence that anyone gains as they get older and have more work behind them, so it no longer feels like a defensive position, but it’s very comforting. It wasn’t born out of some wild hope; it was actually a very safe move, to always keep doing everything.

I’ve been thinking about that, too. You are this large creative force, and you do work in different modes — again, there is this very seamless transition between all those modes, and that is something that comes from being who you were then and explains who you are now?

I think so, because it was a very holistic life. There was no corner in which we were just normal. The way we decorated our apartment, and the way we procured our food and goods (i.e., not always legally), or the ways we made a living — the whole life was the work. Having a whole feminist, revolutionary ethic around it drove it deep in us. All of us from that time still carry that around. A lot of times, it’s stuff that makes no sense anymore, that like only me and Carrie [Brownstein] can talk about, you know? Sometimes my current reality just feels like a pose I’m doing. Though mostly I’m relieved that’s not my life anymore. It was so purposely brutal.

Is there still that riot grrrl — for lack of a better term — “ethos” that lives today?

I see it in the tough women. The famous ones are Tavi [Gevinson] or Lorde, these are young women who are coming up with their own plan. They seem very mainstream, but that’s just the internet. It just wouldn’t exist the same way now — it wouldn’t make sense to make everything private and about five girls sitting in a basement, avoiding the media. Tavi is the media! The important thing now is to connect widely, there’s great power in that.

Also watching 20-year-olds today invent their own genders and really defining how they want to be identified, and what parts of their body they relate to and want to keep — it’s really easy to see that many of my friends in the ’90s were doing that, but minus the NYT coverage and mainstream examples. The language among my friends in the ’90s was more, “I’m a freak, so what, fuck you,” whereas now it’s about actually having rights. That makes me feel hopeful.

So much of your work deals with solitude and this particular kind of real-life awkwardness — is it a response to this age of the internet and communication?

I feel like humans are not very good at connecting, and that’s interesting. I think we’re each bad at it in our own unique way, and each of us does really complex and belabored things in an effort to have intimacy and connect with people. If I end up making a lot of work about alone people trying to connect, it’s not out of some utopic vision of connection, it’s out of an interest in clumsiness. Each person’s art is the unique way they shoot themselves in the foot when they’re most desperate to have someone. I think we all do it in little ways every day. To me there’s something very sweet about that, and if you’re interested in people and characters, that’s where the goods are. I notice that a lot, for example, even [if] an interaction is going horribly, I’m a little bit excited, like, Oh wow, this conversation isn’t working at all! Everything we’re saying is getting us farther and farther away from anything we care about! It’s like a ready-made work of art.

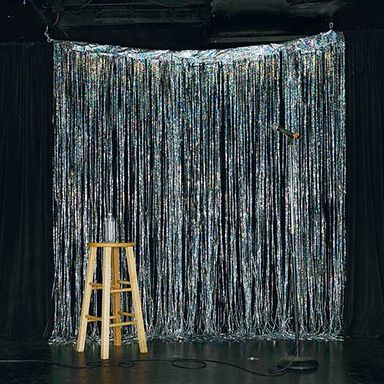

Miranda July, Photo documentation of The Swan Tool, performance, 2001. Photograph by David Nakamoto.

L.J. Roberts, Mom Knows Now (guerilla banner drop on the steeple of the Ira Allen Chapel, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT), Hand-knit yarn. Unkn...

L.J. Roberts, Mom Knows Now (guerilla banner drop on the steeple of the Ira Allen Chapel, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT), Hand-knit yarn. Unknown photographer.

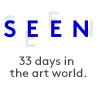

Ginger Brooks Takahashi, Untitled (Diagram of Influences), a personal document of projet MOBILVRE BOOKMOBILE project, 2001–2006. Drawing, color p...

Ginger Brooks Takahashi, Untitled (Diagram of Influences), a personal document of projet MOBILVRE BOOKMOBILE project, 2001–2006. Drawing, color photographs. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Faythe Levine, Time Outside of Time (Sing), 2010–ongoing. Inkjet print. This project documents various off-the-grid, alternative, and intentional comm...

Faythe Levine, Time Outside of Time (Sing), 2010–ongoing. Inkjet print. This project documents various off-the-grid, alternative, and intentional communities in the U.S.

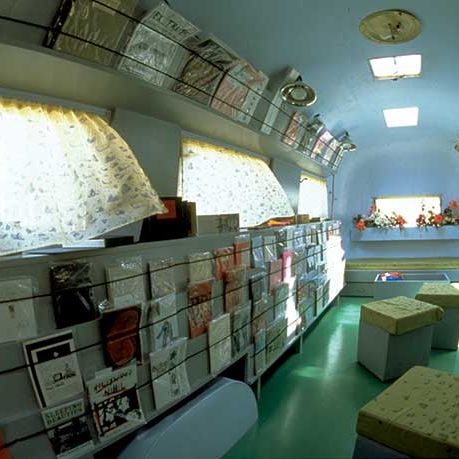

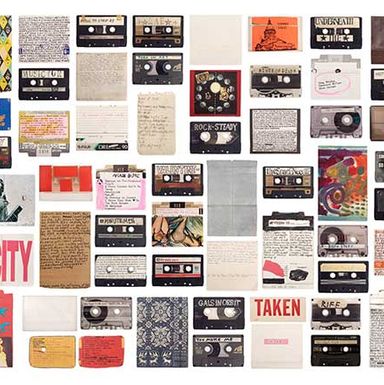

A sampling of zines and distribution catalogues (1991–2013) primarily from the original riot grrrl movement. The zines cover a range of topics such as...

A sampling of zines and distribution catalogues (1991–2013) primarily from the original riot grrrl movement. The zines cover a range of topics such as sexism, empowerment, fat activism, mental illness, gender identity, violence, racism, homophobia, and sex work.

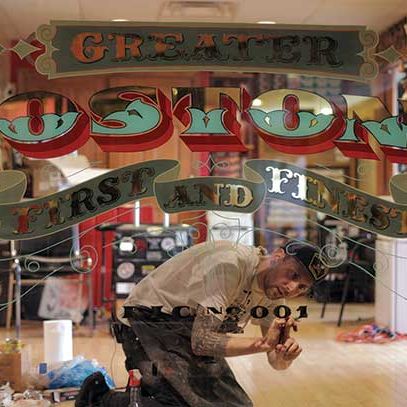

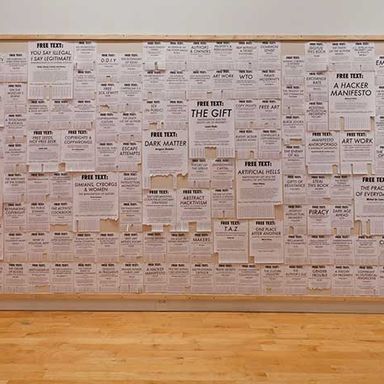

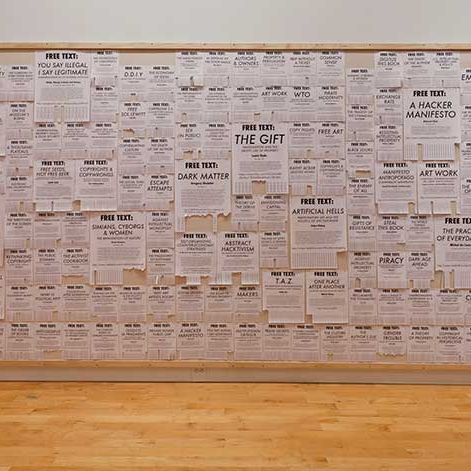

Free downloadable PDF files of texts found online and tear-off tab flyers. By Stephanie Syjuco and courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery,...

Free downloadable PDF files of texts found online and tear-off tab flyers. By Stephanie Syjuco and courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. This project was updated for "Alien She" and includes texts selected by the artists in the exhibition.

Found textiles, taxidermy supplies, appliqué borg, Styrofoam, wood. Recommended Reading (2010), Wallpaper of photocopied drawings. Both by Ally...

Found textiles, taxidermy supplies, appliqué borg, Styrofoam, wood. Recommended Reading (2010), Wallpaper of photocopied drawings. Both by Allyson Mitchell and courtesy of the artist and Katharine Mulherin Gallery, Toronto.