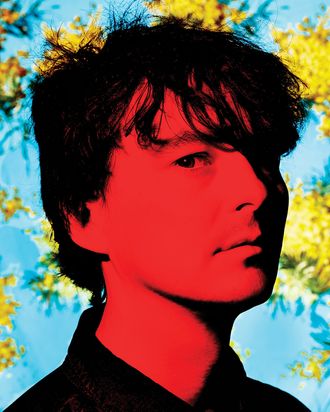

Noah Lennox, the 36-year-old musician known as Panda Bear, is gazing in silence at an elephant turd. We are at the New Museum, taking in the British artist Chris Ofili’s provocative retrospective “Night and Day,” and although we’ve stood before Ofili’s huge, glittering, Giuliani-inflaming depiction of the Virgin Mary as well as the imposing bronze Annunciation, no piece has fascinated Lennox quite so much as this small sculpture titled Shithead, which is made of tiny human teeth, pieces of Ofili’s dreadlocks, and his signature material, elephant dung. Lennox has a lot of questions about the dung. Does Ofili sculpt it with his own hands, he wonders aloud, or does he employ an assistant to do the dirty work? What does it smell like under that glass? The placard next to the piece is no help. Before moving on, Lennox takes one last look at the sculpture and then drops his preferred adjective: “Gnarly.”

Lennox is soft-spoken but affable — which surprises me a bit, given a certain introversion in his music. He’s not shy, exactly; dressed in a gray thermal and navy-blue hoodie, he gives off a sense of some dude floating around in a bubble of easygoing calm. A few minutes into our stroll, though, he looks me in the eye and asks, “Are you sure we haven’t talked before?” He says it genially, but also with weariness: Both as a solo artist and with his band Animal Collective, Lennox has spent much of the past decade either recording, touring, or promoting a remarkably consistent run of albums, including his critically acclaimed 2007 pop collage, Person Pitch, and its more minimalist follow-up, Tomboy. Also, for the past decade, the Baltimore-bred Lennox has been living with his wife and two children in Lisbon; I catch him on one of the last days of a weeklong trip to the U.S. to launch his record Panda Bear Meets the Grim Reaper.

Lennox’s music is the kind often described as “psychedelic,” a word he says he doesn’t mind but often sees misused as a catchall for “made by someone who is probably on drugs” or, even lazier, “colorful.” (Not five minutes later, he spots the word in the wall text of the Ofili exhibit and laughs accusingly.) How does Lennox define “psychedelic”? To him, it’s an uncanny quality where boundaries between things become blurred. Grim Reaper, out on January 13, definitely passes this smell test: It’s a cohesive hybrid of ancient and modern sounds, of meditative stillness and percussive force. Whereas Person Pitch relied heavily on samples and field recordings (on one track, an owl served as backing vocalist), Grim Reaper has more synthetic textures. Listening to it sometimes feels like being inside a video game about Buddhist monks.

Lennox suggests we stop by the second floor and revisit Annunciation before grabbing lunch. The door to the museum’s lime-green elevator closes behind us as Lennox looks to punch the 2 button — only to find that this car skips from the first floor right up to the third. “Now this,” he declares, “Is the most psychedelic thing I’ve seen all day.”

As we exit through the gift shop, we spot a skateboard specially adorned with an Ofili painting of a smiling penis and a 5-year-old having a tantrum because his mother won’t buy it for him. “The style of parenting my parents employed was very hands-off,” Lennox says, walking out onto the Bowery and fumbling with an umbrella. “So I never really had anything to rebel against. I mean, there were rules in the house, but I wasn’t stealing from convenience stores.”

Lennox grew up in a comfortable part of Baltimore; in The Wire terms, he likens it to the part of town Bubbles refers to as “heaven.” “One of the great advantages I had was parents who were like, ‘You wanna do that? Here you go.’” What he wanted around the age of 10 was piano lessons, which led to early experimentations with the family’s Korg synthesizer and 8-track cassette recorder. Lennox started making what he called “doodles … little songs where I was, like, just muting and unmuting parts of it, bringing elements in and out. Really basic. In a lot of ways, I’ve never been able to get away from that Lego-block structuring of songs.”

One day in his late teens, a video captured his imagination and inspired him to take his compositions more seriously: Daft Punk’s surreal, Halloween-shop-purgatory clip for “Around the World.” “I’d never heard anything like that before,” he says. “I didn’t really know electronic music. So I remember hearing that and thinking, That sounds a lot like … well, it’s way better, but that’s the same kind of thing that I like to do.”

It’s starting to sleet, but he’s content to walk. It’s hard to imagine someone this chill ever living in New York, but he did, along with the other members of Animal Collective, between 2000 and 2004. We pass the Mercury Lounge, where the band played an early show, and Other Music, the record store where he worked and was “terrible at talking to people.” New York, he says, gradually turned him “crazy and anxious,” and he found his escape route on a 2003 tour, when he met his wife, the Portuguese fashion designer Fernanda Pereira. Within a year, Lennox had moved to Lisbon. He likes that it’s a little bit out of touch. “Bands never really go through there, but when I was growing up, a lot of people skipped Baltimore too. Portugal is kind of like the Baltimore of Europe.” We settle on Barcade for lunch, where he orders a BBQ-pulled-pork grilled cheese. “I’ve really been enjoying these kind of delights of America,” he says when the sandwich arrives.

Two years ago, Lennox got an email that brought his career full circle: Daft Punk wanted to know if he’d come to Paris and help them out with a song for their next album. “It was kind of a dream,” Lennox says. “I just didn’t want to fuck it up, you know?” He describes the lead-up to his session with the masked duo as “very mysterious,” because when he first arrived at his hotel in Paris, he still had no idea what they looked like. “I was waiting on the street, thinking, Is it that guy? Is it that guy?”

He didn’t fuck it up. “Doin’ It Right” — which sounds like a children’s round sung by a cyborg and a human — was one of the highlights of Random Access Memories, which won a Grammy for Album of the Year. Animal Collective’s success has been more difficult to pin down, but as we chat amid the bar’s soundtrack of generic indie rock, their huge influence hangs in the air. A song comes on that’s built around percussive downstrokes on a slightly out-of-tune acoustic guitar, and Lennox notes, more observationally than accusatorially, “This kind of sounds like we used to.”

The sleet is turning to snow, and we procrastinate, digging in our pockets for quarters and heading over to a Simpsons arcade game. He takes Homer, I play Bart. As we beat up Smithers’s stooges (Homer “can jump really high for how fat he is,” Lennox marvels), Lennox starts reflecting on his adolescence — which, in turn, leads him to talking about his kids. “My daughter’s more of a visual person,” he says. “But my son, you can tell he’s more there [with music]. Weird sounds will happen, and he’s trying to figure it out. But they also change, a lot! At around 2 or 3, you think you’ve got them figured out, and then they’re 6 and you’re like, ‘Where did you come from?’ ” We head into Moe’s Tavern (Level 4, a personal best for both of us). “I feel like I’ve won the lottery over and over again in my life,” he says. “If reincarnation is a thing, my next life’s going to be super-shitty.”

I suggest that maybe he’ll come back as an elephant turd. Instead of laughing, Lennox gives this some serious consideration. “The whole coming-out-of-the-elephant’s-ass part seems pretty lame,” he says. “But if I get to just sit in a museum the rest of the time, it doesn’t sound that bad.”

*This article appears in the December 29, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.