Over the next few weeks, Vulture will speak to the screenwriters behind 2014’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. Which pivotal sequences underwent the biggest transformations on their way from script to screen? Today we talked to writer Anthony McCarten about the late scene in The Theory of Everything where the physically handicapped physicist Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) and his loyal wife Jane (Felicity Jones) realize their marriage has come to an end. The scene is then excerpted below.

In my entire writing career, I don’t think I’ve ever scripted a scene that’s done more heavy lifting with so much less going on on the page. And certainly, there were big, dramatic rewards if this scene could be reduced down to its very essence.

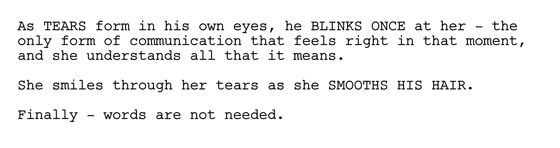

In this scene, very few words had to carry the freight of very big emotions, and that’s an enormous challenge. It’s like a short-story writer restricting himself to now writing just three lines of a poem, yet still trying to say the same thing. It’s an enormous story arc almost all to be done without language, because Stephen is limited to four words a minute. How do you run a relationship where you can’t effortlessly present your side of any discussion? The same goes for Jane’s dialogue. It would be unfair and almost callous if she used weapons that he couldn’t possess, so if he was restricted in his manner of speaking, she would restrict herself, too. That was an enormous challenge, and I had to do multiple drafts that were almost like carving a sculpture, where I’d take more and more away to get down to its constituent parts.

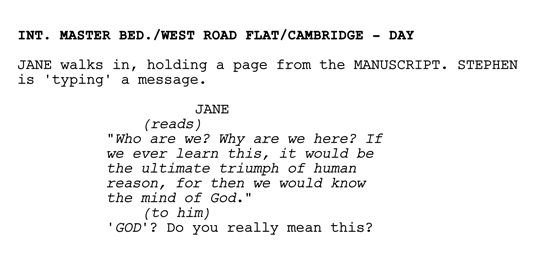

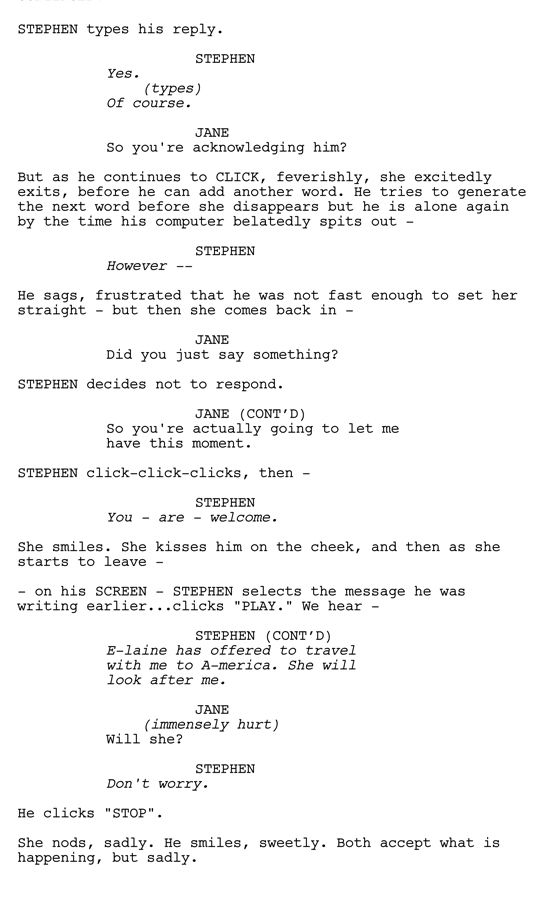

The scene begins by wrapping up the story line about whether Stephen would ever acknowledge God, and Jane interprets a concession on his part, that at least he’s allowed for God. So it starts off very bright and optimistic, and we don’t know that the scene is going to be about a breakup until he hesitates in sending Jane a line about his nurse: “Elaine has offered to travel to America with me.” Why would he hesitate in sending that line to his wife? Oh. It must be about something else. You can see his face cloud with emotion, and you think, Oh my God, is this the end for them?

She’s upset, and crosses the room. Now, what does a man do who can’t get up to comfort his wife? He can’t embrace her, and language is very difficult to acquire at speed. So I thought, What if he does the only thing he can do? He’s in a wheelchair that has a forward gear, so he crosses the room, and in the script I wrote, “He nudges her like a pony nudging its rider.” I know that Eddie and Felicity both said that was a very important line for them, to show the limited vocabulary by which these two people were having to correspond, and how important these little moments in miniature were.

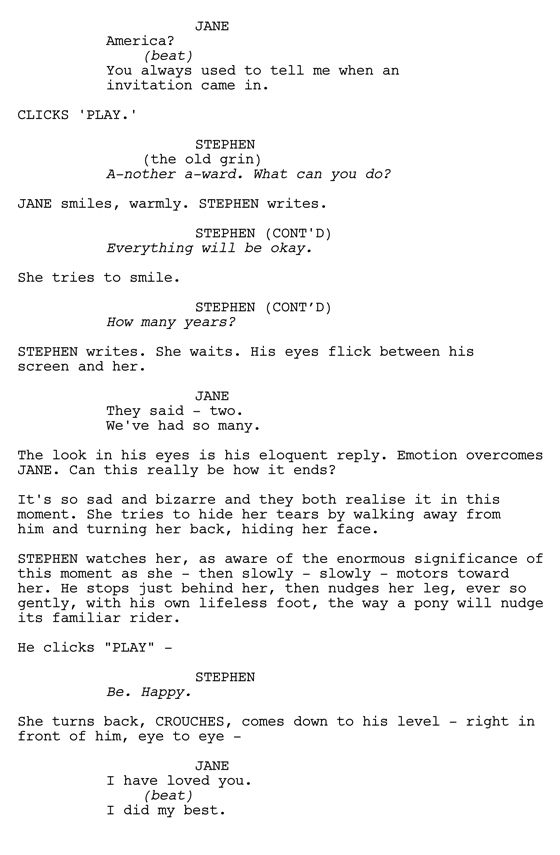

I found that the use of past and present tense were good ways to convey information. For example, she says to him, “I have loved you.” The use of the past tense means that their romantic feelings have played out, but in terms of the story, we haven’t had that beat yet. That’s real news. That means that they both knew that they’d grown apart. That, then, creates a completely different context for when he says he’s going off to America with Elaine. He’s not just throwing Jane on the scrap heap — to some extent, he’s setting her free to go off and explore her own romantic journey with someone else.

One of the reasons I wanted to tell this story is because their love story is unprecedented. I couldn’t think of another movie where you’re asking an audience to go on this romantic journey with both of them where their sympathies could be torn at any moment. It really is a high-wire act.