Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

Amnesia, by Peter Carey (Knopf, Jan. 14)

Great journalism and great fiction both live in the gap between noble ideas and flawed human beings. The saga of Wikileaks certainly dwells there, and so does this Australian two-time Booker-winner’s best work — including this drama-farce of history and hacktivism. After a computer worm unlocks prisons in Australia and the U.S., a disgraced journalist is conscripted to write a book defending the young Aussie perpetrator. Real and fictive history unfolds and fragments, people are kidnapped and freed, conspiracies are unveiled, and full-fleshed characters make it work. It’s just as ambitious and urgent as it sounds, but more fun.

Outline, by Rachel Cusk (FSG, Jan. 3)

Cusk has been both celebrated and scorned for using so much of her life in her writing, but in her eighth novel, the protagonist is maddeningly, intriguingly hazy. This outline of a woman, a writer headed to Athens to teach a writing course, is a sounding board for mansplainers of every stripe: a billionaire, an aging roué, a self-involved novelist, and a few unfocused students. But between the lines of their bloviations, much is revealed (including, finally, the writer’s name). Cusk has crafted another captivating vessel for her thoughts on gender, power, and storytelling.

Against the Country, by Ben Metcalf (Random House, Jan. 6)

If there’s a tendency in rural American fiction toward macho reticence, the narrator of this meaty manifesto against country life, whose thicket of scathing prose opens up to reveal an unhappy coming of age in wretched Goochland County, Virginia, will have none of it. Metcalf invents something new, which you might call the postmodern polemic novel. Like Sam Lipsyte in Homeland, though puncturing red-state myths instead of suburban idylls, he offers the pleasures of both well-honed barbs and well-buried expressions of twisted love.

Doing the Devil’s Work, by Bill Loehfelm (FSG, Jan. 6)

The crime writer’s fifth book, his third in the Maureen Coughlin series and his second set in New Orleans, proves he can navigate its seedy bayous as expertly as his earlier thrillers’ seedy Staten Island. That’s where his complicated bartender-sleuth solved her first crime, before starting over in a place perhaps even more fetid and corrupt. After stumbling on a corpse with a neo-Nazi tattoo, Maureen contends with a power structure entangled with conspiracy-theorizing criminals (this is True Detective country, after all), and Loehfelm reaches a new level of lyrical, site-specific noir.

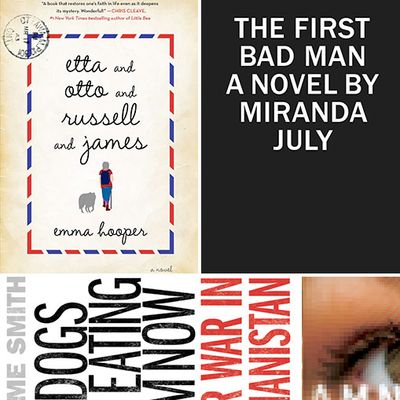

The First Bad Man, by Miranda July (Scribner, Jan. 13)

Some artists get more irritating the better you get to know their shtick. July has the opposite effect. Her work seems to grow deeper and more endearing with each iteration, while retaining its hysterical-neurotic charms and crisp, colloquial wit. July’s first novel is a test of her range, which she ably passes. Single, middle-aged Cheryl Glickman expands from a collection of oddities — a baby obsession, a hallucinated ball in her throat, bizarre sexual fantasies — into someone with real longings, relationships, and opportunities for genuine growth and redemption.

The Dogs Are Eating Them Now, by Graeme Smith (Counterpoint, Jan. 1)

As Afghanistan endures yet another Taliban resurgence, this exemplar of front-lines reporting is finally published south of the (Canadian) border. The war correspondent writes a little about his own country’s conflicted Afghanistan policy but mostly about what he and his interlocutors see on the ground. The fog of war dissipates, and what’s revealed is bleak, sometimes graphic, and often devastating to the big picture. The fruitless war on opium, the torture of the enemy, the reversion to chaos that follows withdrawal — no aspect of our collective quagmire is left submerged.

Etta and Otto and Russell and James, by Emma Hooper (Simon & Schuster, Jan. 20)

You can see why publishers paid high sums for this first novel, whose shifting timelines, plots, and registers contrast starkly with its unchanging main setting, the featureless prairie of Saskatchewan. Etta, 83, decides to cross the ocean off her bucket list, embarking on a 2,000-mile walk with only a magical coyote, James, for company. She leaves behind husband Otto and neighbor Russell, both of whose long, hard life stories also unfurl. Hooper handles the tonal changes, narrative leaps, and gorgeous landscapes with an assurance beyond her years.