“I’m not really conscious of how to provoke interest,” offers Justin Peck, which is a little strange, given just how much interest the choreographer and New York City Ballet dancer is getting these days. He thinks back to the premiere of one of his early ballets, when a critic cornered him. “He was like, ‘People are going to be into your work, then realize you’re not Balanchine and hate on it.’ I was just like, ‘Can I go now?’ ” Peck, holed up in a Tribeca wine bar on a blustery night, laughs and shakes his head. “The ballet world,” he says, “it’s a crazy world.”

That may be, but it’s one in which he’s managed to thrive. Free of gimmickry, Peck’s works uphold and explode classical ballet tenets. Just 27 years old, the San Diego native has already made six pieces for New York City Ballet and was recently named the choreographer-in-residence at the company, where he still dances as a soloist. His next ballet, set to Aaron Copland’s Rodeo, will premiere February 4. Two days later, Magnolia Pictures will release Ballet 422, Jody Lee Lipes’s feature-film documentary of the making of Peck’s Paz de la Jolla.

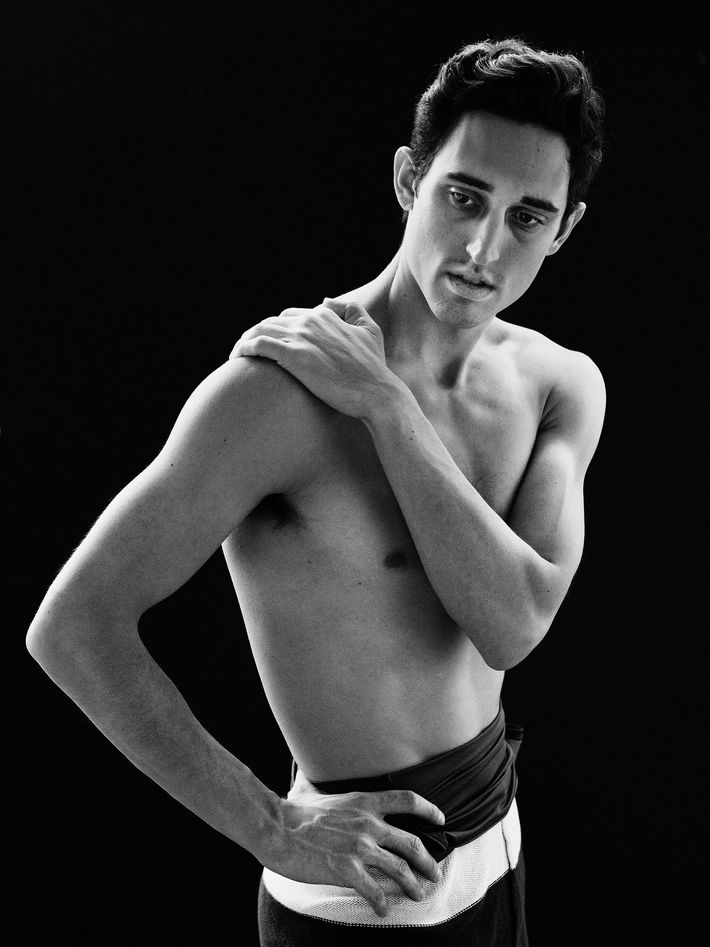

“I was surprised by how young I looked,” Peck says of the first time he saw the film. “I realized, Maybe I am sort of a kid. I guess I don’t feel young.” Peck does seem older than his years: With his thick-rimmed glasses, polite manner, and mop of wavy brown hair, he has a distinctly ’50s-era vibe about him, very much the humble anti-diva shown in Ballet 422. “With Justin,” says Lipes of his decision to make the film, “we wanted to capture that moment in an artist’s career when things are starting to happen, but they’re still learning.”

Despite Peck’s old-hand equanimity, when you watch his ballets, it’s impossible to forget that they’re made by someone so youthful. Each work displays exhilarating invention, from the way Peck showcases the individual charms of corps de ballet members to the insouciant details he inserts at unexpected moments (a boy hopscotching over a row of girls during In Creases). Peck’s dancers look like themselves: cool New York millennials, not princes and princesses of some idyllic realm. “He wants people’s personalities to shine through,” says City Ballet principal dancer Tiler Peck (no relation). In his choreography, Peck loves off-balance movement and rapid directional changes, like pirouettes that finish askew; imperfections that render traditional steps anew and earn raucous ovations rare at the ballet.

Rare too are the expectations he faces. In Ballet 422, at the Paz premiere, a ballet grand dame accosts an awkward Peck, noting that in an upcoming program, it’s his name next to Balanchine’s and Jerome Robbins’s, as if he’s joined them in the pantheon. That sort of adulation, especially so early in his career, makes him uncomfortable. “The process,” he tells me, “is more interesting than standing onstage and hearing people applaud.”

Indeed, the ballet world, desperate for an heir to Balanchine and Robbins, tends to deify bright young men, and as it tries to puff Peck up, he seems determined to stay firmly on the ground, so to speak. “I’m not a very good dancer,” he says matter-of-factly when I ask what his flaws are. “My feet don’t point far enough, my extension is embarrassing. Dance for me has been hard, because it’s a strive for perfection.”

As a choreographer, on the other hand, Peck lets his self-consciousness melt away. “If I get a commission,” he says, “it’s like a flood of creative thought and energy.” Albert Evans, a retired City Ballet principal, coaches Peck as a dancer and serves as ballet master for his choreographed works. Watching Peck create, Evans says, is “like putting on new glasses and seeing something for the first time. To have eight dancers put their heads together and stack them on top of each other” — as they do in Peck’s Year of the Rabbit — “I don’t understand where he gets this!”

During the dance-making process, Peck, an admirer of Balanchine’s “brilliant architecture,” solicits opinions from people outside the City Ballet sphere like Lipes; his collaborator and friend the singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens; and artist Jessica Dessner, whose brother the National’s Bryce Dessner, wrote the score for Peck’s Murder Ballades. Many of his friends, including his girlfriend, ballerina Patricia Delgado, are dancers at Miami City Ballet, where a new work he made in collaboration with artist Shepard Fairey will debut in March.

That Ballet 422 will be released just after Rodeo’s premiere seems auspicious. The film, Peck concedes, shows him at a transitional point, between institutional acceptance and his own wariness of those same institutions. Or, as he puts it, he’s still “figuring shit out.” Rodeo, a reinterpretation of a score made iconic by Agnes de Mille, will showcase how Peck has grown, not to some level of choreographic perfection but to a new comfort with both his own vision and how others see him.

The tension between those perspectives is still there, though. A couple weeks ago, Peck was in Los Angeles for the premiere of Helix, his newest piece for the L.A. Dance Project. The dance was part of an evening celebrating the city’s glitzy Music Center, and the whole thing, recalls Peck, “had this awards-show-tacky vibe. There were violinists inside jeweled pods, and they were floating up and down, playing cheesy music.” Helix, a turbulent piece for six dancers set to music by Esa-Pekka Salonen, was, he says, “definitely different from the rest of the night. I feel like people either thought it was refreshing or were like” — he smiles tentatively — “This doesn’t fit.”

*This article appears in the January 26, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.