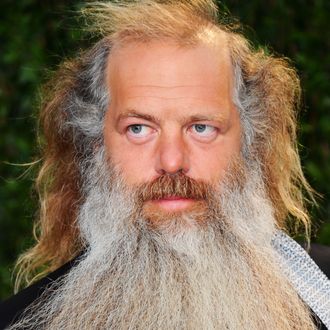

Professional beard grower and legendary record producer Rick Rubin has begun using the annotating service Genius. It’s not the fact that Rubin’s using the site that has people taking note, but rather how he’s using it. As Pitchfork pointed out, Rubin has taken the last three days to essentially turn his verified-user page into a nostalgic stream of diary entries, commenting on songs he’s worked on and opining on other people’s work. All of his notes — which range from interactions with Damien Rice to Jay Z to Metallica — can be found here. Many of the posts give unique insight into the creative processes of the titans Rubin’s collaborated with. We’ve culled through and put our favorite blast-from-Rubin’s-past highlights below.

On Metallica’s “That Was Just Your Life“:

The idea is to allow an artist to see themselves as greater than they thought. Or break down any pre-conceived idea of what they think they’re supposed to be. That’s a big part of it. Take away the self-imposed limitations that artists have for whatever reason. A lot of them are like, “Well this is really what I like because I’m gonna do this because this is what I think someone else is gonna like.”

Sometimes it’s the opposite, where artists have gotten so experimental that they’ve lost the core of what makes them them. And then in those cases, I’ll try to redirect them back. The example might be Metallica. They were kind of lost before and we helped get them back to being Metallica.

On Johnny Cash’s “Hurt“:

You can usually tell which ones I brought to the table. “Rusty Cage” was mine, “Hurt” was mine. He wouldn’t have heard those. Something like an old Jimmmie Rodgers song, chances are he brought it.

There are some exceptions. He brought in a Sting song, a modern Sting song, “I Hung my Head” which is really good. He brought in a Springsteen song, although I don’t know if we ever put it out. He brought in some modern stuff.

There were a lot of songs that he needed to be convincing about. Eventually, he trusted me enough that if I felt strongly about something, he’d do it. I would send him compilations of CDs of songs to listen to, and I remember that on several compilations in a row, “Hurt” was the first song. There’s just something about it. I imagined him saying those words being very powerful.

What I came to realize about that whole Johnny Cash experience was that he was a great storyteller. The song didn’t matter — all that mattered were the words. All that mattered was if the character of Johnny Cash — the mythical Johnny Cash, the man in black — would say those words. If that’s what you would want to hear him talking about, then that would be a good song to do.

So it was never about like melody, it was just about if the lyrics were right.

On working with Slayer:

I can remember Tom from Slayer coming up to me after we’d made a few albums together, and I didn’t work on one or two of the albums after that, and he said: I really don’t know what it is but you do, but whatever it is, would you please come do it again?

I think he liked the records we made together better than the ones he made without me, and he wasn’t sure why.

With them, it really is about, it’s so specific, what they do, that really so much of the job is just not getting in the way. As long as you don’t interrupt them being Slayer, it’s probably gonna be good. They have a flavor. It’s like the Ramones.

On getting Angus and Julia Stone back together:

Did you hear the Angus & Julia Stone album? That one’s really good, came out in August of 2014.

They had put out two albums that were mainly known in Australia. I was at a dinner somewhere in New York and I heard this music playing in the background. After two or three songs, I said “Who is this? This is the best music I’ve ever heard.” And they were like “Oh, it’s Angus & Julia Stone, they’re big in Australia. How come you’ve never heard of them?” So I go home, get their two albums, and listened. Fantastic. You probably know “Big Jet Plane.” For some reason that sample has made it into a lot of EDM remixes.

I reached out to them. It turned out that they broke up. So I met with Julia, and she was really cool. I said, “You know what? How do you feel about making an Angus & Julia album?” And she started crying. She hadn’t talked to Angus in two years. She said she didn’t know if she could do it. I said “Think about it. I think it could be really good.”

Then Angus was coming through, because they were both touring solo — they both made solo albums and were both on their own career path. I met Angus, and he was cool and great, so I talked to him about the idea. I got a call saying that the two of them had a conversation, their first, and they wanted to do it. And then we ended up making this album, which is a really beautiful album, and now they’re closer than they’ve ever been in their whole lives.

The album is like a family healing, and it’s really beautiful. The whole album is great. You won’t believe how many good songs are in a row. Nobody knows about it.

On his first record, “It’s Yours“:

It’s Yours is the very first record I made. At the time, the only place you could hear hip-hop on the radio in New York was on WHBI, WBLS, or 98.7 Kiss, for an hour or two. Magic was on WHBI and then moved to WBLS, and Afrika Islam was on WHBI, where Red Alert was guest of his. Then Red got his own show on 98.7 Kiss.

I felt like all of us made really interesting, challenging records. And they were all different, and cool, in their own way. And then when you listened to a DJ like Mr. Magic, every record sounded different.

On working with the Beastie Boys:

For the most part, with Licensed To Ill, I did the majority of the music, and we all brought in lyrics. Usually, we’d be hanging out all night at Danceteria looking at girls, trying to make each other laugh with lines and writing them down. We were there every single night.

I remember a time when I couldn’t get in.

On Kanye West’s “Only One“:

I was in St. Barths two days before the single came out. Kanye said, “I’m thinking about putting out ‘Only One’ tomorrow at midnight.” I said, “Should we mix it?” He was like, “It hasn’t really changed — it’s pretty much what it was.” I hadn’t heard it in almost two months, so I asked him to send it to me, and he did. And I said, “I think this can sound better than it does.” We never really finished it finished it.

So we called all the engineers — and I’m trying to get all this to happen all remotely — and we got maybe three different engineers. This is the day before New Year’s Eve, and we’re all finding studio time, getting the files. Then they all start sending me mixes. I thought one was better than the others, and Kanye agreed. One guy mastered it, because it was due, and they turned it in. I had another guy master it, and it was better, but it was already too late. I think it switched the following morning. It was in real time! Like as soon as it was better, we had to switch it.

That’s how it works in Kanye world. It used to really give me anxiety, but now I just know that’s what it is. That’s how he likes to work. … Kanye is a combination of careful and spontaneous. He’ll find a theme he likes quickly, and then live with that for a while, not necessarily filling in all the words until later. At the end, he’ll fill in all the gaps.

He was upset at one point when I said that he wrote the lyrics quickly. He’s right — they percolate for a long time, he gets the phrasing into his brain, lives with it, and then lines come up. It definitely starts from this very spontaneous thing.

On Only One, a lot of those lyrics came out free-form, ad-libs. The song is essentially live, written in the moment. Some of the words were later improved, but most of it was stream of consciousness, just Kanye being in the moment.

On Jay Z’s “99 Problems“:

Jay came into my studio every day for like a week, I kept trying things that I thought would sound like a Jay record, and after like three or four days he said, “I want to do something more like one of your old records, Beastie Boys-style.” Originally that’s not what I was thinking for him, but he requested that vibe, and we just started working on some tracks.

Musically, there were a couple of different ideas that [engineer] Jason [Lader] and I were working on independently that we played back together, and the way the beats overlapped was really interesting. It wasn’t planned out, it was more experimenting. … It’s a combination of three samples — “The Big Beat” by Billy Squier, “Long Red” by Mountain, and “Get Me Back On Time” by Wilson Pickett — and two programmed beats coming in and out.

On the disappearance of Lil’ Jon:

Do you remember Lil’ Jon came out and he was really big and then he kind of disappeared because he had trouble with his label? We recorded this song, and it didn’t come out until years after.

I did one song with Lil’ Jon. It’s insane and great. … It feels like it almost never really came out, even though it did. No one heard it. It wasn’t because he wasn’t still great; he just had some issue where he couldn’t get his records out.

On System of a Down’s “Toxicity“:

You’ve got this unbelievable band that don’t sound like anyone else, ever. They’re four Armenian guys. I went to see them live, and every label had passed on them. They were at the Viper Room, it was packed. It was the funniest show. I couldn’t stop laughing. It was intense. The problem with hard music is that it almost all sounds the same. Heavy metal has very strict guidelines. The beauty of System of a Down is that it’s so weird and so groovy but hard as fuck. And the singer is great.

For “Toxicity,” Serj didn’t have words for the bridge. We were at my house doing the vocals and working on the idea, and I remember the idea of the father happening and then us trying to make it biblical in that way. It’s really heavy.

I don’t know what it means, but I know how it makes me feel. It’s like a lot of Neil Young songs, where the lyrics don’t necessarily make sense, but they give you this feeling of something going on. This does that. And it goes from that wackiness of the verse to the epic sadness of the chorus. It’s so weird. And listen to how much harmony there is. Vocal harmonies — no one has vocal harmonies.

On making Yeezus minimal:

When he played Yeezus for me, it was like, three hours of stuff. We just went through it and figured out what was essential and what wasn’t. It was like deciding a point of view, and it was really his decision to make it minimal.

He kept saying it about tracks that he thought weren’t good enough and needed work. If he was going to leave me to work on stuff, he’d say, “Anything you can do to take stuff out instead of put stuff in, let’s do that.”

As of Monday night Rubin had notched 62 annotations, so keep your eyes peeled for more.