Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

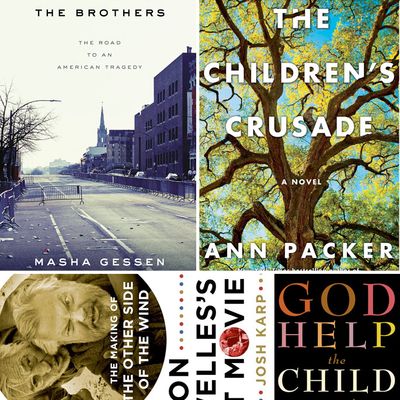

The Brothers, by Masha Gessen (Riverhead, April 7)

The fearless Russian-American journalist brings equal parts sympathy and skepticism to the task of tracking the Tsarnaev family, from Russia’s Chechen enclaves to Cambridge and the Boston Marathon bombing. In her worldview, the shortcomings of the American system have as much to do with the atrocity as Russia’s brutality — to the extent that either can be held accountable for a senseless mass murder perpetrated by idiots. You don’t have to believe all of Gessen’s conclusions to find the journey both fascinating and illuminating on the hardships of life on the cultural margins.

The Children’s Crusade, by Ann Packer (Scribner, April 7)

Packer’s third novel forsakes the dramatic plot twists of her first two (The Dive From Clausen’s Pier and Songs Without Words) in favor of deeper psychological mysteries. A doctor establishes the perfect ’50s family in the future Silicon Valley, but his wife soon chafes at the era’s — and the family’s — restraints. Their four children take turns narrating the aftermath 40 years later, by which point one wayward son has returned with a scheme to sell their land. Packer is an expert American realist at every level, from the interior monologue to the bird’s-eye view.

The Folded Clock: A Diary, by Heidi Julavits (Doubleday, April 7)

It’s slightly fashionable at the moment to blur the lines between contemplation and revelation, fact and fiction, in the mode of Knausgaard, Elena Ferrante, and others. Julavits takes the novel approach of reinventing the form of the diary. Cataloguing two years in middle age in diary entries reconstructed and rearranged, Julavits reveals a whole lot, in often-flawless prose, about motherhood, time, petty jealousies, grand debates, and the irresistible attractions of The Bachelorette.

Orson Welles’s Last Movie, by Josh Karp (St. Martin’s Press, April 21)

It’s fitting that Karp’s story is unfinished; it’s still not entirely clear whether Welles’s last film, The Other Side of the Wind, will finally be completed this year, three decades after his death. Karp’s propulsive chronicle of the botched production is a hall of fun-house mirrors. Welles’s improvised pastiche, begun in 1970, would star John Huston as a brilliant, egotistical director laboring to finish a masterpiece before dying at the age of 70. Fifteen years later, Welles himself died at 70, his masterpiece unfinished — which was far from the end of a story as gripping, probably, as the still-unseen movie.

God Help the Child, by Toni Morrison (Knopf, April 21)

In recent years, the octogenarian Nobel laureate’s work has become sparer, more elemental. This latest novel, following a very dark-skinned, once-ostracized young woman named Bride, recalls Morrison’s 1970 debut, The Bluest Eye. But in a modern twist, Bride’s exotic blackness becomes a lucrative asset in Los Angeles, earning her a plum cosmetics job, a Jag, and all the apple martinis she can drink. When a mysterious lover abandons her, she gives chase, opening up long-buried traumas and, just maybe, the possibility of honest love.

Operation Nemesis, by Eric Bogosian (Little, Brown, April 21)

Famous for blistering monologues and plays, Bogosian dives passionately into an underreported piece of history, a surprisingly effective conspiracy to assassinate the planners of Turkey’s Armenian genocide. Bogosian spends a long time establishing the atrocity’s historical roots before getting to the mesmerizing tick-tock of revenge killings across Europe. His answer to the mystery of why one killer was acquitted in Berlin is almost unbearably ironic in hindsight: Shortly after losing World War I, Germany went easy on the Armenian avenger in order to distance itself from its former allies, the genocidal Turks.

My Struggle, Book 4, by Karl Ove Knausgaard (Archipelago, April 28)

Two thirds of the way into Knausgaard’s mundane, transcendent six-book series on his (slightly fictionalized) life comes a portrait of the artist as a late adolescent — defiantly skipping college to teach and write, without much success; dealing, often face-to-face, with the legacy of his father’s violence and alcoholism while threatening to repeat his mistakes. With more drama and narrative arc than the first three books, it’s a good entry point for the uninitiated. For devotees, it’s another beautiful jigsaw piece in Knausgaard’s great work and ordinary life.

Blood on Snow, by Jo Nesbo (Knopf, April 7)

There’s room in Norway’s libraries (and on monthly book lists) for all kinds of brooders. Olav, who narrates this thriller-novella, may be a shaggy blond lank with a problematic dad, but he shares little else with Karl Ove. He’s a contract killer with the kind of conscience that reduces targets to “units” but rules out bank robberies as too traumatizing. He’s odd, in other words — as odd as Nesbo’s regular series hero, Harry Hole, if less developed. By way of compensation, the compactness of this stand-alone story gives it the quick-strike force of an icicle to the heart.