There are few labels that nerds (present company included) fight about as much as the term graphic novel. It gets tossed around to describe everything from short superhero comics to massive manga tomes, with no clear rubric for when it should apply. But if anything fits that term, it’s the oft-forgotten wordless novels of the early 20th century — and Art Spiegelman is on a mission to teach the world about them.

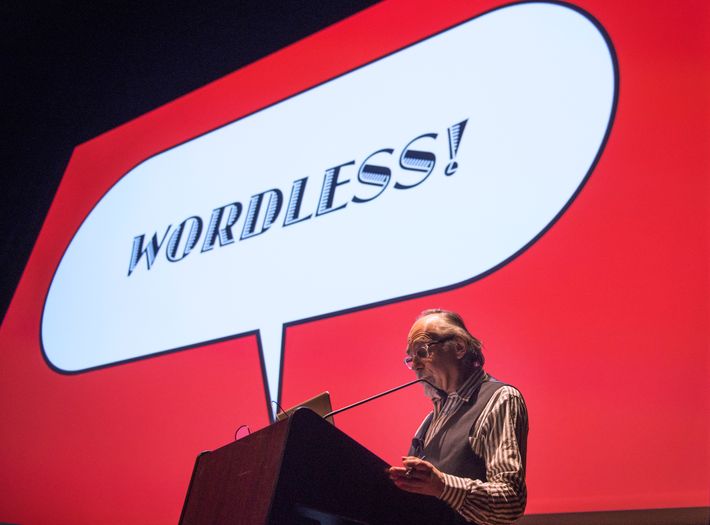

The venerable comics scholar and creator — best known for his epoch-defining comic Maus — has put together a live show called Wordless!, in which he speaks about works of fiction made entirely out of images, focusing largely on the woodcut prints of iconoclastic artists like Lynd Ward and Frans Masereel. The show is a collaboration with composer Phillip Johnston, who plays original works while Spiegelman speaks and presents images. They’ve done the show for sold-out audiences around the country, and tomorrow night, they’re bringing it to Columbia University’s Miller Theatre for an event presented by the Heyman Center for the Humanities. We caught up with Spiegelman and Johnston to talk about Birdman, androgynous superheroes, and Spiegelman’s newfound passion for e-cigarettes.

How’d the show come about?

Art Spiegelman: I decided to come down to the Sydney Opera House for something they do called the Graphica Festival—

Phillip Johnston: Graphic festival.

Spiegelman: Graphic? Oh, okay, I wrote down “Graphica” in the last article, so I figured I had it wrong. I was basically to be interviewed onstage, something they had set up to do with Robert Crumb, but he bailed at the last minute the year before. So I said, “Since you have an Opera House, can I use it?” My good friend Phillip, who’d been a New York–based musician, moved to Sydney about, what, eight years before?

Johnston: Ten years.

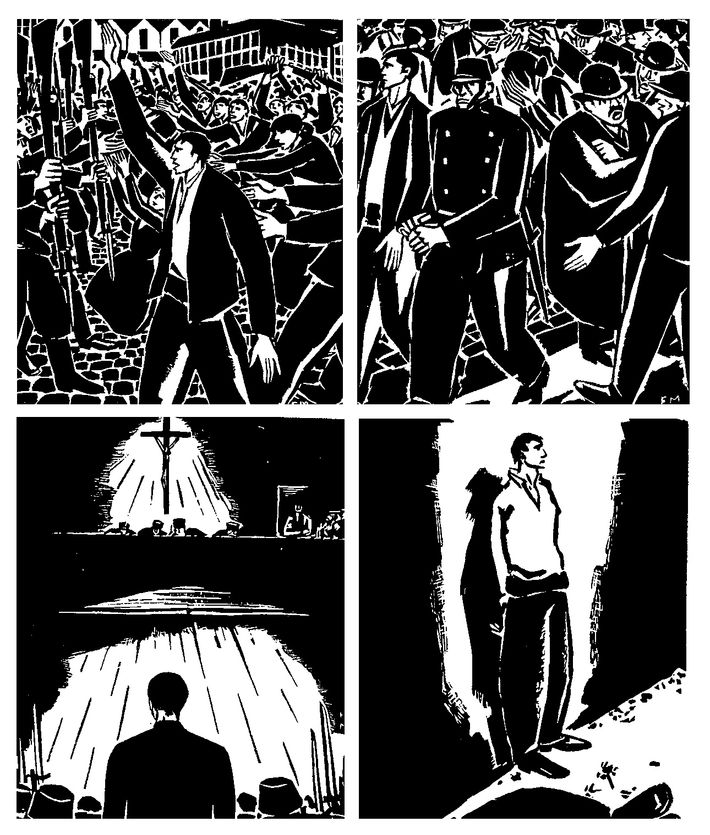

Spiegelman: Eight years before that invite happened. They said, “What have you got in mind?” I was sorta just grasping at straws at the time, but I was very interested in wordless, woodcut novels, on the basis of having put together woodcut novels at the Library of America, the first time they added visual artists to their otherwise-illustrious American authors of the past few hundred years. It occurred to me that if we could find a way to present them publicly, I would be able to explain why they’re so basic to what the fuck happened to comics. I thought Phillip would be perfect for this because he’s done so many scores for old silent films, and this would seem to be an analogous process.

One of the reasons it was interesting to me is that there’s no way to talk about this unless people can understand what the thing is I’m talking about. When I talk about comics, I can show a few panels or a page, but you don’t get to really understand woodcut novels unless you can really experience them. We found a way to let them be experienced in a large group rather than passing books out to people, and then, lastly, we can all discuss this and turn it into — I’ve been trying to figure out what to call it, it’s not an obvious form — it’s either intellectual vaudeville or lowbrow chautauqua.

Phillip, what was your experience with this medium before Art came to you with this idea?

Johnston: Well, I had read some of the woodcut novels. Some of them I discovered through our research, and Art turning me on to them. One of the things that brought Art and I together in the first place is that I had long been interested in a lot of the same areas of comics that Art is interested in, which is underground comics of the ’60s, and the early history of comics, including woodcut novels. Also, we both just have a common interest in things that are totally weird. Woodcut novels definitely fall into that category.

Spiegelman: For me, it’s like, now that “graphic novel” has become the marketing term for “ambitious comics that can do more than tell an escapist, melodramatic story about mutants or deliver a joke,” it’s important to say that the woodcut novel is a real first graphic novel. They’re the ones that actually had that quality of being ambitious, of moving toward a terrain that nobody would associate with comics before [underground comics of] the ’80s. Now we can grasp all of those things back to where they belong. The development and evolution of all these things, they’re wonderful, they’re as wonderful as silent films.

Art, I hear you’re smoking e-cigarettes during the show. When did you transition to vaping?

Spiegelman: Ah, okay. Well, I was a relatively early adapter because I was sick of not being allowed to smoke while doing lectures, and it was really a difficult problem for me. I’d get all kinds of waivers and variances as the noose tightened around all smokers: For example, if something was billed as a performance rather than a lecture, you could get a variance where I just said I was playing a neurotical cartoonist who chain-smoked on stage. But it got harder and harder, then it got harder and harder to find a place to stay that wasn’t right next to the airport in order to be allowed to smoke in my room, and so when traveling I’ve taken to any substitute I could find.

Actually, when the New York Times began to vilify and really create insane, panicked, and hysterical articles about e-cigarettes — like how charging one in your computer made it so the Chinese could get access to your hard drive — they started to seem almost as unsavory as smoking. And that meant I could be a badass and probably live longer if I switched.

Can’t argue with that.

Spiegelman: I got [an e-cigarette] a few years ago as a gift from my daughter. I remember going out to a movie because it was around Christmastime, and we go to see Hugo. A lot of it was taking place in a train station where people are smoking, and the movie’s in 3D, so the theater’s filling up with smoke illusions in 3-D — and I realized, this is the first time I’m able to smoke in a movie theater without anyone trying to kill me! No one would notice my own e-cigarette vapor.

Is the term graphic novel useful in 2015? And, if so, for what?

Spiegelman: Yes. Marketing. After that, it gets so problematic. It really is useful to having people come around and feel less embarrassed about reading something that has speech balloons in it.

Didn’t the late comics giant Will Eisner say he just came up with the term to sound classy so he could get girls?

Spiegelman: He told various stories. He was a great, great comic book artist, and a wonderful bullshitter, and a genius marketer. I don’t mean to sound dry, but I would say that the phrase was invented by some college fans in the ’60s, and woodcut novels were part of their evidence that such a thing theoretically could exist as a more sophisticated comic. I had a perfectly good marketing term, which was a long and ambitious comic book that needs a bookmark and asks to be reread, but somehow graphic novel took hold. What can you do.

My problem was more of a personal problem that has to do with, when I grew up, being aware that I was going to make comics and that they weren’t going to be in any standard category. I would say that I do comics and then, like Will Eisner, I’d have to like really grope to explain it or find another career that I can say I was involved in, like, Oh, I’m a graphic designer, I’m an illustrator. I became allergic to superheroes. I was interested in absolutely everything about comics except superheroes, which I saw was a worn-out trope. But now I’ve warmed up even to [legendary superhero comics artist] Jack Kirby, whom I spent decades being allergic to.

Really? What Jack Kirby stuff do you find interesting to look at?

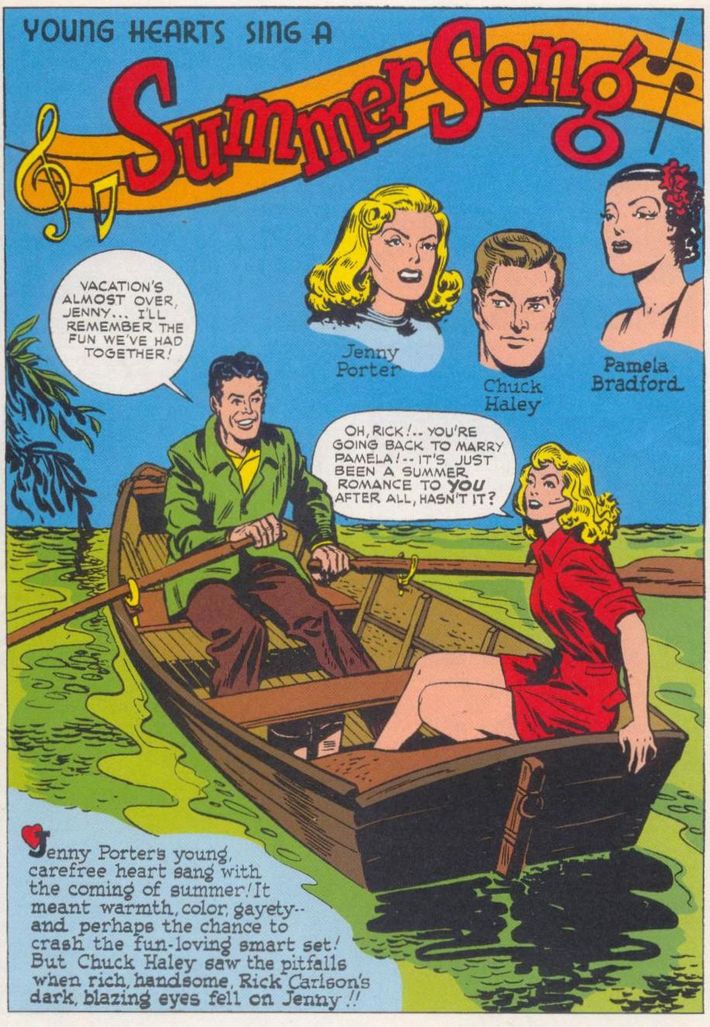

Spiegelman: Well, now you’re going to laugh at me. I really love his romance comics.

No, his romance comics are great. He’s able to convey emotion on faces, even with his blocky lines, very well.

Spiegelman: His stuff is so three-dimensional. I realized he’s actually a primitive, and I can’t blame what grew out of his work in the surrounding industry on him. It’s just like Henry Darger: It’s this insane fantasy world filled with endless wars and battles, and neither of them ever saw what a woman actually looks like.

Art! You can’t say that about Jack Kirby!

Spiegelman: They all look like guys in drag to me! And at this point, cisgender is just one possible gender, so I’m happy with that whole array. I’ve found that every woman he’s ever drawn looks like she could beat me up, which is a great accomplishment.

This is going to sound like a very tangential question, but I promise you it’s not. Have you seen American Sniper, the Clint Eastwood movie?

Spiegelman: I’ve actually been avoiding it. Why, is he reading a graphic novel in it?

There’s this scene where the main character walks in on a fellow soldier who’s reading a Punisher comic and gives him a hard time about it, and the soldier gets very defensive and says, “It’s a fucking graphic novel, man. There’s a big difference.” It was then that I knew I was gonna hate that character.

Spiegelman: [Laughs.] It sounds like in 2015 it’s now become a blur all over again. At this point, Punisher comics do call themselves graphic novels. It took a while for this all to sort out, but now there’s a strata of stuff a lot of people seem to be interested in unabashedly. We have strayed from the mutant reservation, and I’m grateful for that. We’re seeing more interesting comics now than almost any era since the critical comic days.

Phillip, sorry, we’ve been neglecting you here. How did you —

Spiegelman: For Phillip, to answer a question I’m sure you have on your notepad already: The music is not exactly like making music for silent movies.

What a mind-reader you are. Yes. Phillip, what are the differences between scoring a silent movie and a woodcut novel?

Johnston: Silent films are much more open, they don’t guide you as directly to one interpretation. One of the pleasures of writing music for silent films is that you can leave an understanding of what’s going on a little more open. In the case of the wordless novels, because we’re presenting the succession of the sequence at a tempo, at a pace that we’ve decided on to make an entertaining show, the function falls much more directly on the music to really support this. Not only the storytelling, but even the visual storytelling, in the sense that the music can guide your eye as to what to look at in a particular picture. You really have to be much more detailed and analytical about what you’re gonna do with the music as far as what’s happening visually.

What was the last superhero movie either of you saw?

Spiegelman: Birdman.

Did it echo some of your frustrations with the superhero-storytelling genre?

Spiegelman: Yeah, I mean, my frustration is not as urgent as it was. Now I’ve made my peace with it, because when you say you make comics or graphic novels, people don’t automatically assume it’s got a cape. As a result it’s all open, and even, like you said, the results don’t have to be [a] superhero movie. What was your last superhero movie, Phillip?

Johnston: Oh, man, I can’t even think. I guess the closest thing I’ve come to a superhero movie is Frank. [Laughs.]

Frank? Oh, the Michael Fassbender movie.

Johnston: Yeah. It’s pretty cool. I don’t go to superhero movies.

Spiegelman: But you must have went when your son was a little bit younger.

Johnston: Oh yeah, when my kids were young, we used to go to all the animated films. I love that stuff, like The Incredibles. My son’s gotten into old superheroes like the DC comics of the ’50s and ’60s. The main thing that we share together is Plastic Man and those early DC comics.

Spiegelman: I’m grateful for one thing on the internet, which is now, they’ve been uploading tons of comics from the ’30s and the ’40s [to online archives]. Now I understand why most people had no use for comic books: They were just an industrial product. It was hard to even figure out who drew one story rather than another, and you get in the house style. But by having so many of them available now, I just go leafing through them every day, and I feel like I’m back at a drugstore spinner-rack. I love the people who are kind of eccentric, either trying to do something really ambitious or just genuinely stupid. Those people are drawing in such a wrongheaded way that it becomes amazing to look at.