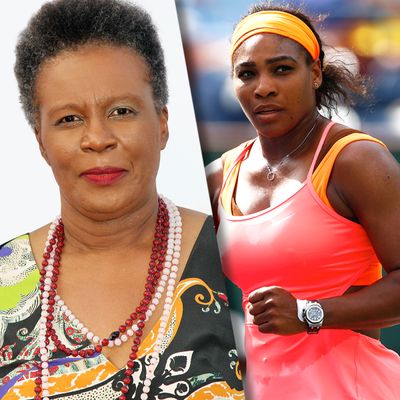

Last week was an eventful one for the writer Claudia Rankine. On Thursday her book┬áCitizen, a shape-shifting treatise on American racism, won a National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry, having also been nominated as criticism. The following day, one of her bookÔÇÖs key subjects, Serena Williams, returned to Indian Wells, California, for a tournament sheÔÇÖd boycotted for 13 years. Serena had been booed for the entirety of her championship match there in 2001. Fans suspected that her father and coach, Richard, had engineered her sister VenusÔÇÖs withdrawal from the tournament, but the Williams family reported hearing racial epithets and vowed never to return. This February, following a decade and a half of Grand Slam victories and minor controversies, Serena announced a change of heart. After an emotional first match on Friday to roaring applause, she advanced yesterday to the quarterfinals. Rankine has only caught highlights between cross-country book-tour stops, but she did find time to talk to us about the latest twist in the life of a champion for whom, as she wrote, ÔÇ£every look, every comment, every bad call blossoms out of history, through her, onto you.ÔÇØ

How did you feel about Serena breaking the boycott?

I think itÔÇÖs fantastic. In her statement to Time announcing it, she said an incredible thing, and I wrote it down: ÔÇ£Thirteen years and a lifetime in tennis later, things feel different. A few months ago, when Russian official Shamil Tarpischev made racist and sexist remarks about Venus and me, the WTA and the USTA immediately condemned him. It reminded me how far the sport has come, and how far IÔÇÖve come too.ÔÇØ In essence, what she said was, for the first time, an institution stood behind me. When Tarpischev referred to the Williams sisters as ÔÇ£the Williams brothersÔÇØ and the USTA fined him $25,000 and put him on a yearÔÇÖs suspension, that made all the difference. Because you canÔÇÖt legislate crazy or racist, but if the rest of us stand around and let it happen, thatÔÇÖs when you feel like youÔÇÖre totally on the outside.

Reading in Citizen that the electronic line-call system was installed partly because of a series of bad calls against Serena in 2004, I couldnÔÇÖt help thinking about body cameras on cops. Both are technological remedies not only for human error but blatant bias.

Vigilance is great, but we can never have a camera at every angle. So the Darren Wilsons will exist. They will kill random black men no matter what happens. But what throws black people out of the American citizenry is when it goes to the courts and no indictments come. ThatÔÇÖs the real problem. You can have institutions that will arrive immediately and legislate against that.

So how do you feel about the Justice Department report on Ferguson?

I think that Eric Holder showed up in this instance. And I donÔÇÖt remember what school it was, but the fraternity with that song ÔÇö immediately that was shut down, and thatÔÇÖs all that you want: a kind of communal recognition that that is not acceptable. Not that you can stop it from happening. I mean, when Richard Williams was accused of match-fixing, that is not far off from why black men are being killed. It was the immediate assumption that heÔÇÖs a criminal.

He and Venus are still not coming to Indian Wells. If SerenaÔÇÖs making the right call in 2015, what about them?

ItÔÇÖs not a question of right or wrong. ItÔÇÖs a question of comfort level. Serena feels okay, and clearly she herself was very nervous in that first match, yeah? I mean, it was a tough match for her. The trust that Serena has based on what happened with the Russian official is something personal to her. But I donÔÇÖt think you can underestimate the wound and the personal disappointment one has, because these incidents are not singular. They accumulate in the body, and youÔÇÖre negotiating them all the time.

So you buy that the fining of the Russian official was the main reason Serena came back?

She did say last year she was considering it, so clearly, itÔÇÖs not the only reason. But itÔÇÖs never a single thing. SheÔÇÖs at a point in her career where sheÔÇÖs clearly understanding herself now as a legend. I think she is seeing herself almost as a stateswoman for the game.

The chairman of the tournament recently told the Times┬áthat SerenaÔÇÖs was a way of ÔÇ£deletingÔÇØ that ÔÇ£terrible dayÔÇØ of the 2001 final from the tournament. Is that even possible?

ThereÔÇÖs no wiping the slate clean, itÔÇÖs always part of the story. The fact that the story has taken this other turn is fantastic. Serena said something like sheÔÇÖs glad that she can create new memories, and I think she felt overwhelmingly moved by the response of the crowd and the fans. We could see that in her tears.

Some people have attributed SerenaÔÇÖs polarizing moments to her familyÔÇÖs cliquishness, or perhaps to sexism. Is it definitely all about race, do you think?

I think so. Look, weÔÇÖve had the opportunity to watch how the president has been received. And just recently, the letter that went out behind his back ÔÇö what is that?

Well, it doesnÔÇÖt seem to have gone well for the Republicans.

Exactly, but still, just the sense that this is a possibility, an appropriate response. So, no. Sexism is rampant, but I think that the black body in the white imagination is still equated with bestiality, criminality, on some level. ItÔÇÖs one of those things that canÔÇÖt seem to untangle itself.

And yet a black man is president, and a black woman is the best tennis player in the world.

Well, thatÔÇÖs why I think itÔÇÖs fantastic that SerenaÔÇÖs gone back. You donÔÇÖt want to stand still, you want things to keep moving. You want history to be forced to adjust itself in terms of the past. But it doesnÔÇÖt mean that dynamics from the past are gone just because we have a new kind of fluidity and openness in certain areas.

How did Serena become a dominant topic in Citizen? ThereÔÇÖs obviously a lot more going o in this country when it comes to racism.

Well, I was really interested in Tiger Woods when he arrived on the scene. My husband was a big golf fan, and he would watch and I would be in the other room listening to the commentators. The ways in which he was always being accused of breaking the rules made me begin to watch when it was on, and that somehow led me to watching Serena and Venus. Then I started playing tennis myself.

You also have a chapter on Zinedine Zidane, the Algerian-French soccer player who head-butted an opponent in a World Cup final after being taunted with racial slurs. Why do sports interest you so much as a cultural barometer?

ItÔÇÖs documented. You have both commentary and action simultaneously and instantaneously. So itÔÇÖs not just about watching whatÔÇÖs happening, youÔÇÖre also hearing how itÔÇÖs being interpreted at the moment that itÔÇÖs happening. And so part of the fascination for me as someone who teaches and reads cultural theory is, youÔÇÖre not only interested in what the athlete is doing, youÔÇÖre interested in the ways the commentators contextualize what is happening. And then you have your own interpretation as well.

Citizen puts Serena WilliamsÔÇÖs struggles with judges and fans on a continuum from the insensitive comments you and your friends have heard to the killing of African-Americans by cops and vigilantes. Why was it important to unify all of these experiences in one short book?

I wanted to create a narrative that showed that these microaggressions reveal a kind of positioning that allows people then to arrive on juries, and to arrive in the Senate, and to arrive in police cars, or in New Orleans organizing evacuations; that that positioning of the white imagination is inside all people. ThatÔÇÖs how we get to those bigger moments. WeÔÇÖre not in the world of self-declared white supremacists. WeÔÇÖre in the world of regular Americans who hold those premises or beliefs unconsciously.

WhatÔÇÖs the remedy for that?

I think consciousness is a big step, and it shouldnÔÇÖt be underestimated.