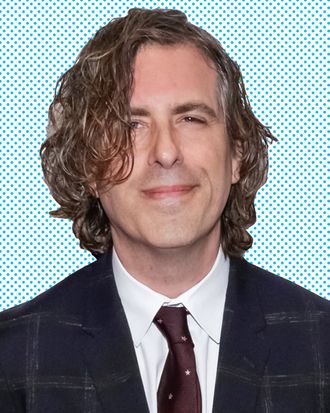

When Courtney Love gave director Brett Morgen, who was known for his sharply focused documentaries like The Kid Stays in the Picture, access to a storage room full of Kurt Cobain memorabilia to use as raw source material for his new documentary Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, she told him he could do whatever he wanted with what he found; she didn’t want to micromanage and hadn’t been through the material herself. “I trusted him,” she told a crowd after a recent screening during the Tribeca Film Festival. To Morgen’s delight, tucked away in the storage facility was a box of unheard cassette tapes recorded by Cobain, including the 1988 sound collage he titled Montage of Heck. Morgen’s one instruction from Love and executive producer Frances Bean Cobain was to humanize the son, brother, husband, and father who unwittingly became the voice of a generation. As one of the most mythologized figures in rock and roll, he says, it was not easy. Morgen set about his work by using the wealth of original art, diaries, home movies, cassette tapes, and other materials found in the storage facility as guide posts for what he describes as a “family origin story.” It starts with Cobain’s childhood in Aberdeen, Washington, and ends abruptly on the eve of his suicide in 1994.

Morgen has been working on Montage (at the Tribeca Film Festival this week, in theaters April 24, and coming to HBO May 4) since 2007. During that time, a protracted legal battle between Love and her daughter kept the film in limbo. “There was a tsunami of shit in between,” said Love. “I caused most of it, but it’s all smooth now.” After he screened the film for the two of them for the first time, Morgen says he went into a bathroom and wept for 25 minutes. “It had to do with the fact that from that moment on, I was going to be drifting away from Kurt,” he confesses. “That for years, he was the central focus of my work, and I felt like I spent more time with him than anyone outside of my immediate family.” Vulture spoke with Morgen while he was in Amsterdam during the final night of a European promotional tour and on his way back to New York for the film’s U.S. release, about making the documentary, developing an intimate relationship with Kurt, and the film’s reception.

What was it like when you discovered the cassette tapes in the storage room?

That was a really big find, but one of the misconceptions of Kurt’s storage facility is that there was a limitless amount of materials, and I’m thrilled that people may think that from watching the film, but the truth of the matter was there wasn’t. There was a lot of art, and there was a tremendous amount of audio, but there’s very little film footage of Kurt Cobain outside of performances and interviews. We had wonderful documentation of the first eight years of his life, but there’s a huge hole up to, say, 24 years old. I often say it’s what you don’t have that can be a blessing rather than a curse because it informs how you’re going to approach the film. What we did have was Kurt’s art and his audio. Nobody had told me when I was going through the storage facility that we were possibly going to find that, and to be quite honest, I didn’t even know if I was supposed to touch it or not, but I was there, and I was certainly going to. When I opened the box, I saw 108 tapes. It could’ve just been 108 rehearsals, as far as I knew, I didn’t know what it was, it wasn’t marked or anything.

What was your first reaction to the material? What sort of audio did you find?

So we’re going through this stuff with no road map and no guide, and suddenly I start coming across this amazing material. There were hours upon hours of Kurt and Courtney playing together, doing music together, recording music together. I don’t know what to call it because it’s not recording music. They were just jamming. While it’s not used in the film, that gave me tremendous insight into their dynamic and their relationship because it’s unfiltered media. I felt like I was a fly on the wall listening to these conversations. Then we came across some unheard music, hours upon hours of stuff that was then incorporated into the film score. I also found an audio autobiography. That was a total revelation. It led me to the conclusion that in order to tell Kurt’s story properly, I couldn’t rely on Kurt’s interviews with the media. I needed to tell the story through Kurt’s art. That, to me, is where the true expression and experience lies. Here’s an artist who created probably the most comprehensive oral and visual autobiography of anyone from our generation. That sort of became the filter of the film; that it would be Kurt’s interior journey through life as depicted through his art and supplemented by interviews with the people who were closest to him throughout his lifetime.

With so much new and unheard material, including a cover of the Beatles’ “And I Love Her,” getting a soundtrack out must feel like a obligation. Do you think a soundtrack will be released this year?

I’m not in control of these things. I’m hoping it is, and I know that they’re negotiating it as we speak. I really hope that it sees the light.

One of Frances Bean Cobain’s goals for the film was to humanize her dad. What is the best example of that in the film?

Pretty much everything that exists outside of the media filter allows us to arrive at a much deeper understanding of who Kurt was. I don’t think he was quite comfortable in a lot of those experiences when he was being filmed for the media. He came alive to me every time we stepped away from that. His voice was different, his mannerisms were different, you could see him smile. I don’t think I ever heard Kurt laugh in public.

The interviews with Cobain’s family members are particularly dark. How did you get them to speak so candidly on camera?

One of the things that I was struggling with was that first 15 minutes of the film, because in many ways, it’s a very different film when his family is telling the story. They’re defining Kurt, and we’re not allowing his voice to be heard because a lot of what they’re talking about happened when he was 2 years old. I love the moment when Kurt emerges, because you remember his stepmom says, “I don’t know how anyone can deal with that sort of rejection,” and it’s like call-and-response. All of a sudden, the drums kick in really aggressively and Kurt’s screaming through a song. You see artwork from his childhood that was Mickey Mouse and Goofy, and now it’s monsters and bats and a horror show. His idea of the American dream had become tainted and polluted, and it was all being expressed with art. You see the anger and the abandonment and the disillusionment; suddenly you’re seeing these burning homes where five years earlier there had been a drawing of a white picket fence.

Suicide figures very prominently in his life and in the film. Why did you decide to end before that final moment?

I thought the story was complete. I didn’t think that there were any questions left. There was enough information for the audience to draw their own conclusions. No one really can ever know why someone decides to end their life, and we’ll never know. Most of what happened is mired in a lot of gossip and innuendo and finger-pointing. For me, the story had come to a logical conclusion.

Was there any talk of donating proceeds to a suicide-prevention center?

I don’t know if there will be proceeds, but I just was talking to the animator who did all of the beautiful renderings of Kurt and the oil paintings in the film, and I told him I wanted to sell off a bunch of the paintings to raise money for suicide prevention. We’re discussing opportunities available to us to try to give something back, whether it’s to musicians or to artists, but I think that would be a fitting testament to Kurt.

In your Times interview, you said once the film wrapped, you went into a bathroom and cried for 25 minutes. What happened?

I just got overwhelmed with emotion. It had to do with the fact that from that moment on, I was going to be drifting away from Kurt. That for years, he was the central focus of my work, and I felt like I spent more time with him than anyone outside of my immediate family. I got to know him, I felt, in a way that was much more intimate than I feel like I know most of my friends. I was looking at these primal thoughts that people generally don’t share with one another. I was overwhelmed with grief about not being able to be with him anymore, and that this was it. And then I started thinking about my own children, and the time that I had to spend away from them while making a film about Kurt’s relationship with his child, and it hit hard, it was just overwhelming. Oftentimes I find when you’re making these films, it almost feels like a fuckin’ war, man. It was just a very emotional undertaking.

The premiere at Sundance was met with critical acclaim. Did you expect such a response?

The response really caught me off-guard. I didn’t expect there to be such a rapturous response, I figured the film would’ve been more polarizing. I was prepared for that, and it’s not like one can say that it feels really satisfying because of the circumstances of how it ends.

How would you describe Frances Bean’s creative contribution to the film?

Well, Frances wasn’t involved creatively in the film. She explained to me what she was hoping the film would be, and then I showed her the film when I felt it had arrived at a cut that was worth sharing, and she told me not to touch a frame. But this film doesn’t exist without her. None of these parties would’ve come together to support a Cobain project without her support. What she said to me at our first meeting was, “I’m not a filmmaker, this is your thing. I’m doing my own thing. I’m creating my own art, this is your project. I don’t want to be involved in the day-to-day constructions of the film. I have no interest in that.” She really respected my autonomy. Her support was immense. Her influence was incredible, and if she didn’t want this film to be seen, people would not be seeing this film. Without her, straight-up, this film doesn’t exist.