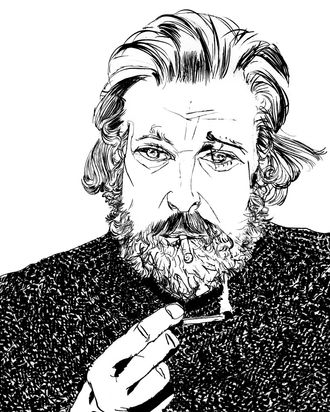

Last spring, Karl Ove Knausgaard came to New York to promote Boyhood Island, the third volume of his six-part series of autobiographical novels, My Struggle. The line to see him interviewed by Zadie Smith at the bookstore McNally Jackson stretched around the block, and there appeared to be a Knausgaard look-alike outside (though he might have been a stray Euro-hippie). One night later, Knausgaard spoke with Jeffrey Eugenides at the New York Public Library. He talked about some of his main themes, the undifferentiated nature of experience (“It’s completely possible to sit at home and read Heidegger and then next moment you go and do the dishes — it’s the same world”) and what happens when the body dies (“For the heart, life is simple: It beats for as long as it can. Then it stops”). Reading from his books, he stood swaying a bit like a folksinger and a bit like a graying, blue-eyed Christ.

Eugenides closed by reading from a passage about an “early puberty orgy” at the end of the third volume and asked if the episode really happened. “Yeah,” Knausgaard replied. “Norway is a wonderful country,” Eugenides said. The audiences on both nights were conspicuously full of novelists and critics, whom you don’t often see gathered in the same place, unless they’re present to talk about themselves or there’s an open bar.

Around the same time, of course, one of the things they were talking about over their highballs was the problem with Knausgaard — or really with the people who had fallen for him. In The Nation, William Deresiewicz agreed with those who praised Knausgaard that the Norwegian had created an immersive world but argued it was merely a world of surfaces, and that when critics “enthrone” Knausgaard the effect is “to cede reality to the camera.” There was soon another dissent, not to do with Knausgaard’s achievement but his popularity. On the New York Review’s blog, Tim Parks pointed out that for all that had been written in praise of Knausgaard in the U.S., he’d sold modestly (40,000 copies of the first two volumes by last spring, according to the Times, or not quite a capacity crowd at Yankee Stadium). So perhaps the hype in America around Knausgaard was that of a writer’s writer on steroids — or that of an author with a vocal faction of critical support, on the one hand, and, on the other, a cult writer whose frustrated neo-Beat romanticism attracts shaggy youngsters across state lines to queue up around the block in Nolita. (And possibly to protest: I was recently forwarded an invitation to a “Ban Knausgaard” party in Brooklyn, which might feature dartboards with the faces of Karl Ove and his champion James Wood.) Lately, Knausgaard has been overtaken in voguishness by another author of a multipart autobiographical epic, the pseudonymous Italian Elena Ferrante. Last month on The New Yorker’s website, a headline asked, “Knausgaard or Ferrante?” The comparison wasn’t all that enlightening (protagonists of both series are oppressed in their youth by “patriarchy,” but who of us isn’t?), and the question indicated that American readers might not have room in their heads for more than one trendy foreign-language novelist at a time. (Bolaño or Sebald? Murakami or Houellebecq?)

There are a lot of reasons why Knausgaard would appeal to other writers more than he might to the (mythical) average reader, some of those reasons extraliterary, including envy. In Norway, where there isn’t much of a frank autobiographical tradition, Knausgaard’s disclosures about his family caused a genuine nationwide scandal, and his sales are measured in terms of their ratio to the country’s population: one in ten. (For an American writer, equivalent success would mean selling one book to every resident of New York State, New Jersey, and Connecticut.) His struggle has been a writer’s struggle — against the shadow of his father, against the obstacles of being a father himself — and part of his triumph has been to become completely unblocked, writing at a pace of 20 pages a day, once managing 50 in a 24-hour sprint, and completing a 550-page book in eight weeks. Then there’s the audacity of taking your title from Hitler and selling out your entire family in the process (“Judas literature,” 14 of his relatives called the books in a signed public letter). Plus, he’s fiendishly photogenic and now attracts lucrative stunt assignments from the likes of The New York Times Magazine, which recently published his meandering two-part travelogue of North America, notable for its serial violations of journalistic code: You are not to dramatize your foul-ups with travel documents; celebrate, in the essay, the size of the check you are earning for writing it; make your photographer your main character (besides yourself); or attest to seeing nothing but homogeneous junkspace in the place you’re visiting and gaining no insights into its culture. (I hope next year they send him to Rio.)

But it’s the way Knausgaard breaks the rules of fiction that’s kept people reading for thousands of pages, that’s thrilled those who’ve praised him and irritated his detractors. In the former camp, Jonathan Lethem, Wood, Smith, Eugenides, and the rest have seen something liberating in My Struggle. A critic like Deresiewiscz sees a disavowal of the duties of literature. Both sides are looking at the abandonment of refinement, of the burdens of fashioning plots, of psychologizing characters, of showing and not telling — of the burden of authorial empathy itself. Reality in My Struggle is a matter of one thing simply happening after another. At its best it takes on a propulsion effect. The experience of reading Knausgaard is less like that of reading Proust (a frequent comparison) than of watching a recording of a great athlete, say, a basketball player, on the court. There’s constant brilliance, but it’s not in the nature of the game that every shot lands, and many of them don’t. Not when the game is played at 20 pages a day.

Names enter and leave the narrative, often without becoming much more than names. They’re people drawn from the author’s memory, but through the eyes of his narrator, they can seem like figures in a landscape or animals observed on a Nordic safari. It’s tempting to call Knausgaard’s the art of the failure to connect, but failure implies trying, and the impression that My Struggle leaves is that connection is not a possibility. Or even, really, a wish. Family members are conveyed only through “character traits … manifested.” From Volume 2: A Man in Love:

When I think of my three children it is not only their distinctive faces that appear before me, but also the quite distinct feeling they radiate. This feeling, which is constant, is what they “are” for me. And what they “are” has been present in them ever since the first day I saw them. At that time they could barely do anything, and the little bit they could do, like sucking on a breast, raising their arms as reflex actions, looking at their surroundings, imitating, they could all do that, thus what they “are” has nothing to do with qualities, has nothing to do with what they can or can’t do, but is more a kind of light that shines within them.

Whatever this is — and I think there’s something beautiful about the idea and the way it’s explained — it isn’t empathy. The paradoxical effect is that the reader’s tendency to identify with the narrator is all the more powerful. And the strange thing is that the narrator, Karl Ove — from boy to tween to teen to man to father — is no Everyman. He’s a pretty fucking weird dude.

A death-obsessed misanthrope prone to phases of acute alcoholism and flights of sanity-ceding passion, one of which — after his future second wife rejects him — results in an episode of face-cutting: Does everyone who claims to really see themselves in this mirror? Maybe they do, maybe I do, and you can count me as one of those who’s often thrilled by My Struggle. So it pains me (a little) to report that Volume 4: Dancing in the Dark — like Boyhood Island — is a lesser work than the first two books (though better than the third). It does display just how thoroughly Knausgaard can inhabit his previous selves, including his most magnetically misanthropic ones, but while writers know how difficult this is to do, others may find the book too thoroughly submerged in late puberty and its humiliations. If I were in a generous mood, and could profess to any expertise in the Scandinavian canon, I might call it the great Norwegian premature-ejaculation novel.

The first such emission occurs on page 27, and after a few more episodes, the narrator stops counting them. It’s risky to attempt to inhabit the mind of a 19-year-old male and to try to do so honestly. Knausgaard is always taking this risk. In Boyhood Island, you feel that you’re inside the mind of a child, and the book’s suspense derives from Karl Ove’s fear that his father could lash out at him at any moment, without much cause. The first two books are told from the perspective of adulthood, with a necessarily higher level of sophistication. That Karl Ove is an intellectual who’s aware that modern life requires a man with a family to make certain compromises (taking care of the children, doing some housework) but who still yearns for a heroic pre-Enlightenment sort of masculinity he knows isn’t available to a member of Stockholm’s polite middle class. Teenage Karl Ove isn’t shy about saying he wishes he could bash a girl over the head with a club and drag her back to his cave by her hair.

Not all of Karl Ove’s thoughts about sex are so hormonal and coarse. But they are unremittingly adolescent. He also venerates women and imagines sex as a path to transcendence. At 19, Karl Ove is still possessed of his virginity (nothing at that tween make-out orgy went below the belt for him), and one of the book’s central questions is whether and how he’ll lose it. Will it be with one of the several girls he feels a true flame for, or will it go to one of the many more he encounters on his drinking binges and visits to discos? He spends a year (1987–88) as a schoolteacher in a village in northern Norway: Will he cross the line and become involved with one of his students, who are only a couple of years younger than he is and seem to be constantly turning up at his house uninvited, or play it safe with one of the few age-appropriate women in the village? Will his inexperience doom him forever? Much of the narrative is absorbed by these questions, and they’re no doubt true to a certain male experience, but they’re among the book’s weakest parts. It’s hard not to think that Knausgaard has strained the novel by being too true to his priapic younger self. (I’ve not mentioned masturbation: He swears he’s a late starter, and still doesn’t even know how.)

A little after 100 pages, time shifts back two years to the aftermath of his parents’ divorce, a flashback that continues for 250 pages. Scenes of his father’s incipient alcoholism, which we know will kill him a decade on, and attempts to regain his son’s affection lend the book a dose of gravity, until Dad’s drunken fits of anger put Karl Ove off from coming to see him. Knausgaard does little of the frame-breaking here — the digressions and digressions within digressions, a valid reason to compare him to Proust — that set off the first two books. But there’s a brief flash forward to the days after his father’s death when his older brother, Yngve, discovers their father’s notebooks documenting these days in terms of insomnia and its relief through alcohol: “Another bad night. Always like that when you don’t take any ‘medicine.’ ” The notebooks yield a classic Knausgaard line: “We don’t live our lives alone, but that doesn’t mean we see those alongside whom we live our lives.”

The end of gymnas (Norwegian for high school, basically) occasions a phase of all-out debauchery among the graduating class called russ, where the book builds a Kerouacian momentum as Karl Ove enters a phase of ceaseless daytime drinking and starts smoking hash. He feels little remorse when his mother kicks him out of the house one day when he stops by to get a change of clothes and cracks a six-pack of Carlsberg; for his classmates, the town has become a rotation of parties they roll up to in “the russ van,” in which Karl Ove can always crash. In his own diary, he writes that these were the happiest days of his life. He soon moves north for his teaching job, and it becomes clear that his loneliness and sexual frustration are to a certain extent self-imposed: He means to become a writer. Like sex, this will be a way for him to access the sublime. The stories he writes in the early-morning hours before school, as conveyed in summary by Knausgaard, are parodically heavy with symbolism (e.g., a vision of a plain dotted with bonfires that turn out to be funeral pyres), but of course we know he succeeded at that. As the book ends, he’s off to writing school. But does he ever get laid? Reader, the answer is on the penultimate page.

*This article appears in the April 20, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.